By N. David Milder

Introduction

My intent in this article is to help increase the understanding among downtown leaders and stakeholders (downtowners) in communities with populations under 25,000 about the potential impacts that the arts can have on their districts as well as the types of research techniques and data that should be used in assessing those impacts. (However, much of the content also is applicable to downtowns in larger communities.) Hopefully, such an improved understanding will lead to more realistic expectations, consequent better planning, and more successful arts projects and programs. Optimistically, it will also enable downtowners to more accurately assess just how strong an economic engine the arts can be for their downtowns.

Downtown Arts Impact Studies Should Be Structured to Meet the Needs of Downtown Leaders and Stakeholders as Well as The Arts Organization’s Board and Its Donors.

If downtown arts venues cannot have positive benefits for their districts, then they might as well be located anywhere else in their counties or regions. As a result, the concerns of downtowners should be addressed in any studies of arts venues’ economic impacts. Art organizations that do not do that are being extremely disrespectful to their neighbors – and some of their staunchest political supporters. Of course, these organizations may simply fear that they have insufficient positive impacts on their district and do not want that known.

I have done 20 downtown assignments in which possible arts projects and programs were important elements. I cannot remember a single downtowner raising the issues of how much the proposed arts entity would buy from downtown businesses, or how many new jobs they would create or their ability to raise household incomes in the whole community or county. In my experience, downtowners, in municipalities of all sizes, are primarily interested in how a new arts venture might affect:

- Downtown Businesses. What would their audiences spend in their districts and how would that affect downtown businesses, especially retailers, restaurants, and hotels? Would it attract strong new businesses or strengthen existing merchants? What would happen in the county or city as a whole are at an entirely different level of concern for them.

- Downtown Properties. Very importantly, how would a new downtown art venue affect the rents, occupancy rates, appraised values and real estate taxes of nearby downtown properties? Would it spark nearby building improvements and new construction?

- How the Downtown Works. Would new arts venues raise the level of pedestrian traffic and increase the numbers of the downtown’s out-of-town visitors and persistent local users? Or improve their attitudes toward and perceptions of the downtown, while also having positive effects on the downtown’s appearance, walkability, traffic congestion and parking needs?

If I am correct and the above describes fairly accurately the information most downtowners would like to have, then those needs should heavily influence what an economic impact study of a downtown arts entity should cover. These needs are a lot more fine–grained than some often used impact methodologies can produce.

Some may argue that things like visitor attitudes, the district’s physical appearance, its walkability, traffic, and parking do not strictly fall under the purview of an economic analysis. Yet, those factors have important influences on site selection, the operations of many downtown firms, and the critically important downtown visitation rate. To deny their inclusion in a purported economic study seems plainly dogmatic and idiotic. Of course, the best thing to do is not to take my word, but to ask your own involved downtowners about the types of impacts – current or potential –they want to learn about.

Limitations of Input-Output Models for Downtowners. At the regional, county or multi-zip code level, these models can estimate how many arts audience expenditure dollars will be captured by business operations and how they then will re-spend those dollars. However, they have the following strong deficiencies for downtowners:

- They cannot be applied to geographies as small as the vast majority of our downtowns. They just don’t work at that level since the needed data are too iffy or unavailable.

- Even more importantly, they cannot ever say anything about how arts audience expenditures influenced: business expansion, the opening of new businesses, higher rents and property values, improved property conditions, etc. They cannot address most of the information needs of business people on these issues even if their concerns would be at the regional or county level, where these models are most easily applied.

Arts Advocacy Efforts May Have Different Information Needs. A very important reason that impact studies of downtown arts venues and organizations have not been driven more by downtowner information needs is that they mostly have been undertaken for advocacy reasons. They accordingly tried to meet the information needs of the government officials, foundations and large corporations who would provide needed donations and/or permissions and approvals. The need of arts organization leaders to respond to donor needs and government approvers is certainly understandable, and input-output models and the variables they can address are often well suited for doing that.

Impacts Involve Senders, Receivers, and Re-Senders: It’s Very Important to Know Their Characteristics.

Impacts are relationships that involve two basic types of entities: the “sender” that causes the impact and the “receiver” that is being influenced by it. The sender has outputs. They turn into impacts when they are absorbed by a receiver. For example, a new theater’s audience generates more customers and higher revenues for nearby restaurants. The receivers can then become “re-senders,” passing along part of that impact to still other receivers: e.g., the restaurants increase their orders to their wholesale food suppliers. The I-O models used in many impact analyses recognize and quantify these types of relationships among the variables they can analyze. This is a simple example of “the multiplier effect’ of any economic activity.

Problems are generated when analysts focus too much on the impact senders and their acts of sending and fail to analyze the presence and ability of the impact receivers to catch and absorb what is being thrown to them. For example, if a small downtown does not have any restaurants, then there is no entity present that can catch the new audience’s dining dollars. If there are some restaurants, but they are of low quality, have a bad reputation, few seats, or are open only for breakfast and lunch, etc., then they probably will not capture many of the audience’s dining dollars. Ignorance about potential impact receivers’ characteristics is particularly dangerous when analysts are trying to identify the potential positive impacts of a new arts project or program. Estimating what the new arts endeavor will throw off is hard enough, but an equally important question is how much of it the receivers are likely to capture.

Sometimes, what a sender is emitting is so strong that it can induce the attraction, creation or expansion of a receiver. For example, a new small town theater is a big hit and attracts a large audience that generates enough potential diners that someone opens a new restaurant. That may sound simple but may not happen all that easily. A typical full-service restaurant nationally will need sales of between $150 PSF and $250 PSF to break even. A restaurant with 1,500 SF would need annual sales of between $275.000 to $375,000 to make it; one with 2,500 SF would need between $375,000 to $625,000 (1). Among a sample of 23 communities with populations below 25,000 (more about these towns below), the median amount of expenditures for meals and drinks generated by their arts events’ audiences was $994,542. The 1,500 SF eatery would need to capture between 15% and 25% of the audience expenditures for meals and drinks; the 2,500 SF restaurant between 38% and 63%. Of course, other consumer expenditure factors might also come into play in the determination of whether a new restaurant will open, e.g., the incomes, spending habits and preferences of the local trade area’s residents and non-resident members of the downtown’s daytime population. Furthermore, my research suggests that in communities with populations under 3,000, it is somewhat easier for a restaurant to enter a market because they only need a relatively small market share to survive financially. However, the quality of the food and service at such a restaurant may not be comparatively high. Such factors further underscore the point that just knowing how much the audience will spend is a very necessary, but insufficient step for determining arts venues’/events’ impacts on the downtowns they are located in. Analyzing the impact’s receivers and the environment in which they are located is also essential.

Additionally, sometimes what the impact sender is emitting is too weak to have much effect on a receiver. For example, the Country Gate Theater in Belvidere, NJ, (population around 2,600) has seating for 200 and 15 performances scheduled for its 2017 season. If they were completely sold out, the total audience would be 3,000 people. If every audience member spent $10.20 (the average for arts audiences in 23 towns with populations under 25,000, more about them below) in local eateries, the total potential direct impact on local restaurants would be about $30,600. That’s not a lot, even though I’ve optimized the scenario. Also, it’s capture will be potentially split among the local eateries – and others more distant.

Theaters and PACS in communities with populations in the 15,000 to 35,000 range that I surveyed online had seasons with 80 to 90 performances. Some theaters are only open during the summer months, while others, to the contrary, have heavily reduced schedules. Many museums in smaller towns are only open one to three days a week; others only have those sorts of schedules in the warmer months and are otherwise closed. When these arts venues are dark, they generate no customer traffic or spending for other downtown businesses.

Impacts Seldom Occur in Isolation: There Are Usually Multiple Senders (Causes).

The renovated Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan – a venue for many performing arts events such as outdoor movies, plays, dance and music concerts – has had impressive positive impacts on its surrounding neighborhood. In no small measure this is because it has been able to “mobilize the neighborhood,” i.e., it strengthens and mobilizes other existing nearby impacting forces.

As illustrated in the above diagram, first, Bryant Park had positive impacts on two existing buildings: the Grace Building, and the American Radiator Building that later turned into the Bryant Park Hotel. Then these three entities all had positive impacts on the construction of 1 Bryant Park (BoA) and years later the four entities all helped stimulate the construction of 7 Bryant Park. Notably, both the Grace and American Radiator buildings had inherent strengths and magnetism, so they could benefit significantly from the area’s improved image and higher visitor traffic induced by Bryant Park’s renovation. The new construction of One and Seven Bryant Park was facilitated by the renovated park and the more desirable Grace and American Radiator buildings through both direct and indirect causal paths. Bryant Park’s renovation, because of the quality of the office building stock, was able to “mobilize the neighborhood” and help induce new construction. As time passes, and the neighborhood further improves, Bryant Park’s impacts will become more and more indirect, while other important entities appear that are also exerting positive impacts of their own as well as passing along indirectly some of Bryant Park’s influence.

This is important: if the nearby buildings had been in worse condition, the park’s renovation would have had far less impact on their rents, occupancy rates, and capital value. That implies that if a replica of Bryant Park was created in a far more decayed environment, the magnitude of its impacts would probably be significantly less because it would have far weaker neighborhood “co-impacters” to affect and mobilize.

Because so many impact studies are done to advocate support for a particular arts organization or a specific arts project, their focus is all too often on the present or future benefits produced by them. However, in the real world, arts organizations and projects are likely to have favorable impacts on a downtown only if a number of other forces are involved that also have important impacts. In many instances, their impacts will be greater than those of the arts entity. The impacts of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (LCPA) on the Lincoln Square neighborhood are instructive.

Impact studies have rightly claimed that Lincoln Center influenced a great influx of housing units that then attracted a good deal of retail development. What the studies failed to note was the nearby presence of Central Park, the Hudson River, several busy subway stations and the Midtown Manhattan CBD. Each, individually, may have had a stronger impact on residential development than the LCPA – especially the renovated and revitalized Central Park. Combined, these four factors definitely had far, far greater impact than the LCPA on neighborhood housing development. However, and strategically important, the physical development of the LCPA probably sparked the initiation of the neighborhood’s housing resurgence. It took down many decayed structures and replaced them with buildings filled with uses that brought into the neighborhood a lot of more affluent and well-educated people. That may have been its most important role in the neighborhood’s impressive resurgence.

LCPA’s direct impact through its audience’s spending on retail probably has been relatively modest. Residential growth probably has had the strongest direct impact on Lincoln Square’s retail. LCPA undoubtedly also had some indirect impacts on retail via its direct impacts on housing.

Why is this important? If you are trying to figure out what the impacts of your proposed arts endeavor will be, it is important to identify the other factors, both positive and negative, that might be in play. They can make a critical difference in determining whether a potential impact is likely to happen or not, its magnitude, and if it is likely to be beneficial or harmful. Also, if you are thinking of making the arts the engine of your downtown revitalization, maybe you need to include some other engines as well!

Determining The Impacts Of An Existing Arts Project Or Program Is Much Easier And More Accurate Than Determining The Impacts Of One Being Proposed.

There is an obvious and simple explanation for this, but it still needs to be stated because it is such an important point: the existing projects and programs will have a lot of essential data on admissions, ticket sales, overall revenues and expenses, building and land costs, etc. Estimates must be made for proposed projects and programs and though they may be produced through diligent work, they still will have significant built-in potentials for substantial errors. Finding comparables to use in estimating the impacts of new projects is not easy since there is often a lot of variation in the aforementioned types of information among arts organizations, even those in communities of roughly similar size. Additionally, such estimates are often the foundation for other estimates, so one substantial initial error can undermine the entire quantitative analysis.

It is best to treat such estimates for new arts endeavors as having ballpark accuracy and reliability and stating so frequently in reports, press releases, etc. I would argue that impact analysts should exercise great prudence in stating their findings and overtly acknowledge the potentials for errors. When dealing with the future, analytical modesty and caution are always in order. PR puff is an enemy.

Accurate Information About Downtown Arts Audiences’ Expenditures Is Essential If An Impact Analysis Is To Be Accurate And Useful.

Americans for the Arts (AftA) has just published an enormous amount of valuable information about arts organizations in 250 study areas around the nation (2). For this article, I have extracted information for 23 that are in towns with populations in the 1,500 to 25,000 range. AftA groups together town, city and county study areas with populations under 50,000. However, to me and to some other economic development specialists I conferred with, the 25,000 population threshold more truly focuses on the smaller communities this article is primarily aimed at. The table below shows the expenditure components in their 2015 budgets as well as their audiences’ expenditures. Total organization expenditures and total audience expenditures are two key data inputs in AftA’s impact analyses for each of these communities. They represent the very important direct impacts. If you go to http://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/research-studies-publications/arts-economic-prosperity-5/use/arts-economic-prosperity-5-calculator you can get a ballpark estimate of the event related audience spending of your arts organization by providing three pieces of information: town size; its total expenses and its total audience. However, these estimates should be treated as very ballpark since they are not based on a survey of your arts venue’s audience, but on “the average dollars spent per person, per event by cultural attendees in similarly populated communities” as revealed by surveys in those communities.

Arts Organization Spending. The table shows that total organizational expenditures average about $5.6 million or 44% of the combined total, though the median is about $2.6 million, or 52% of the combined total. That suggests the organizational expenditures are more important among the smaller organizations. Such expenditures are substantial and obviously an important channel through which the economic impacts of these arts organizations flow. However, an essential question is how many of those expenditures are likely to go to downtown businesses? The basic geographic unit of analysis AftA uses, counties, does not facilitate generating an answer.

One approach to answering this question is to assess the likelihood of the arts organizations’ expenditure items having related vendors located in their downtowns that can capture them. The above table shows how the Paramount Theater in Rutland, VT, spent its money in 2014. Of the $1,480,086 in expenditures, about 57% was for performance expenses (mostly for out-of-town talent) and 19.9% for salaries (most of which probably was not spent in the downtown because it does not dominate the city’s economic activities.) Of the remaining 24%, the associated line items potentially can be captured by downtown firms, but the Paramount’s CPA, for example, is not officed downtown and most of its other business and professional services vendors probably are not as well. I have also looked at the expenditures of several art museums around the nation and they show a similar story regarding the likelihood of nearby firms capturing their organizational expenditures. Moreover, many of them were not located in their downtown and were too big to be easily accommodated in one. I fear downtowns, especially the smaller ones, are highly unlikely to capture any large proportions of their downtown arts organizations’ expenditures because they have thin business mixes. Moreover, even in large cities, many of the vendors serving arts venues are not located in their neighborhoods. For example, much of the scenery and costumes for Broadway shows in NYC are created or stored in NJ, Brooklyn and other parts of Manhattan.

It should not be burdensome for an arts organization to identify its vendors who are located in its downtown and to total its payments to those vendors in a way that preserves anonymity. They might use their IRS Form 990 responses as a report structure. If they cannot do that, then a lot of other questions should immediately be asked of its managers.

Arts Audience Spending. The AftA data above shows that, on average, the expenditures of the audiences of the 23 smaller town arts organizations were larger, about $7 million, than those of the organizations themselves, about $5.6 million. That is the channel through which most downtown arts venues potentially can impact local businesses.

The best research tool for getting information about what the audience expenditures purchase is a survey based on a significantly large number of interviews. I would suggest at least 600 respondents are needed, the more the better. However, such surveys are notoriously hard to do because respondents’ memories of non-repetitive expenditures, such as how much they paid for dinner last night, or smaller incidental items, are likely to quickly fade. The surveys also can be expensive to conduct. The best approach is to do intercept surveys at arts events and ask about expenditures that happened within the last day. AftA has developed a good questionnaire to use that is available on its website, though downtown organizations might want to amend it somewhat to reveal expenditures made in their districts. With a bit of good training, staff or volunteers can administer it at local arts events. Of course, the questionnaires then have to be made machine readable and properly analyzed. The latter can require professional expertise and experience.

Some of our nation’s most prestigious arts organizations have had studies conducted of their impacts that –done on the cheap, quick or easy — were based on surveys carried out neither by them nor the research firms they hired, but by still other organizations with unrelated research objectives in mind. Other arts impact analyses were based on surveys that were too small, poorly worded or amateurishly administered. Every other piece of analysis based on those poor audience expenditure surveys was, garbage in-garbage out, worthless. Getting a good survey done of your downtown arts organization’s audience spending is a sine qua non for getting a fairly accurate and useful analysis of your existing arts program or project. Properly planned and executed, they can be quite affordable.

Here Is A Real Problem For Downtown Arts Advocates Of New Projects Or Programs: There is no existing actual audience for your proposed arts endeavor, only a potential one of uncertain size. Still, there may be other arts events in your district or community with audiences that could be surveyed. However, if they differ in when during the day their major visitation occurs or in how long the visits last, the results would require very careful and skilled interpretation.

If there are no local audiences to survey, the estimates might be made based on what has been found in comparable communities. Finding a truly comparable community or a group of them is not an easy task– and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Audience Spending Patterns In A Sample of Smaller Towns With Populations Under 25,000.

The 23 towns I selected from the AftA data set to look at this question all are comparable in that they have populations under 25,000. However, if you look closely at the survey-based estimates of the audience’s total expenditures for meals and drinks and overnight lodgings in each study area, you find that the ranges between lows and highs are quite large. Also, looking at averages may not be the most prudent thing to do. For example, in 19 of the 23 study areas, expenditures of non-resident audience members were below the overall average for all 23; for resident spending 14 of the 23 were below average. In a normal distribution, 11 or 12 would be below the average. The medians appear to give a better indication of where most of these study area audiences are.

The table above shows the total, average and median expenditures for each audience spending category in these 23 towns. It has two parts. The top displays the results for audience members who are local residents; the bottom covers audience members who are not local residents. The results for the average smaller study area seem impressive: about $3.69 million from non-residents and roughly $3.38 million by residents. Expenditures for meals and drinks are $1.11 million and $1.39 million respectively. However, a more conservative approach is probably more prudent, since so many of the 23 study areas have below average audience spending and most other arts venues in similar communities are likely to as well. Looking instead at the estimates of total spending based on medians shows significantly lower spending levels: the average median of total spending by non-residents is around $1.03 million and about $1.1 million by residents. Spending for meals and drinks are respectively estimated at $401,488 and $593,054.

The per person spending of audience members – see above table — as might be expected, reflects the patterns displayed in the aggregate category totals. Estimates of the total per person expenditures are very interesting. For non-residents based on the means is $42.94, and $31.54 based on the medians. For residents, the estimates are $20.27 and $17.35 respectively. The per person spending for meals and drinks by non-residents averaged $13.52, with a mean of $11.12, with residents averaging $8.84, and having a median of $7.95. To put some perspective on that spending level:

- In 2015, the average meal in the 22 largest family restaurant chains was around $28 per person. Red Lobster, for example, was at $20.50, Outback at $20.00 and Red Robin at $12.17 (3).

- Bryant House, near the Playhouse in Weston, VT, has seven entrees on its menu that range in price from $15 to $19.

- Roots, around the corner from the Paramount Theater in downtown Rutland, VT has several entrees all priced between $19 and $23.

This suggests that per person arts audience spending in these smaller communities is not relatively high. That means that to get any really significant aggregate audience expenditures, the arts venue must attract a significant number of admissions.

This is demonstrated in the table below. For each expenditure item, it simply takes estimates of the total expenditures based on averages and estimates of total expenditures based on medians at the study area level and divides them by the daily average and the daily median of per person spending. This is done for resident and non-resident audiences combined. The resulting estimates are the number of audience spending days needed to generate the total expenditures at the study area level for each expenditure item.

Planners of new arts venues in smaller communities should keep these statistics in mind when assessing their potential economic impacts. As should downtowners when advocates for new arts projects come a–calling.

The Biggest Audience Expenditures Go To Firms In Hospitality Niches. Expenditures for Clothing Are Negligible, But Those for Gifts /Souvenirs Can Be Significant.

Whether one looks at the averages or medians, data at the study area level or at the per person expenditure item level, the patterns are persistent and their strategic implications for downtown revitalization leaders are clear:

- The biggest POTENTIAL impacts of art venues are through their audiences’ POTENTIAL spending in hospitality type establishments – places that provide accommodations, food, and drink. For example, per person expenditure Items associated with a hospitality niche – refreshments and snacks, meals and drinks and overnight lodging – accounted for an estimated 61.2% of the total resident audience’s spending based on study area averages and 71.7% with estimates based on medians; 66.8% and 71.3 % respectively of the non-residents’ expenditures.

- Meals and drinks are the biggest single expense items (41.4% mean-based and 53.2% median based) for resident audience members and 30.3% and 38.9 respectively for the non-residents. So restaurants have the most opportunity to benefit from arts audience spending. Overnight lodging is the second biggest expense item for non-residents. (These observations are from the table above with the title starting: Categorized Audience Expenditures by Attendees).

- The potential impacts of arts audience spending on retail are very narrowly focused on just a few types of retailing.There’s little to no impact on such essential small town needs as a grocery or pharmacy.

- Audience spending for clothing is relatively meager. Downtown leaders should not expect such spending to help sustain their existing apparel shops or to stimulate their expansion or to attract new ones.

- However, arts audience spending for “gifts” may be significant. Unfortunately, their impact paths are not easy to research. Such expenditures may HELP attract art galleries, crafts shops, bookstores or gift shops that offer an array of such products, though huge amounts of book and music sales are now on the Internet. Moreover,

such spending pales in comparison to that for food, drink, and lodging. - Valparaiso, IN, has adopted a downtown revitalization strategy based on growing its hospitality niche and strengthening its strongly related Central Social District functions. Those are potential revitalization engines that all downtowns should also seriously consider.

Examples of Arts Audience Spending Looked at With Some Additional Information About the Local Context.

From an impact perspective, behind many of the things that downtowners want to know about a potential arts endeavor is this issue: can it favorably influence the decisions of businessmen that are related to the downtown? Will it, for example, make them feel more financially secure, or spark them to expand their operations, or to open new ones? It is hard to provide the necessary answers without an assessment of these operators and the overall market conditions in which they operate. However, some indications of what those answers might be can be obtained if we look at the downtown context in which the arts venue is situated. Often helpful in putting data about arts audience expenditures into a clearer perspective is identifying:

- The relevant trends affecting the downtown. For example, today apparel shops are facing strong headwinds (e.g., e-commerce and deliberate consumers) that probably will not abate any time soon.

- Simply if there are currently firms in the sector being looked at and their characteristics. If there are no establishments, then the related audience expenditures cannot be captured. Starting a new firm to capture them is far more complicated than for an existing firm to do so. But, weak or badly managed firms are unlikely to capture many of these dollars and may, in fact, be on the verge of closing.

- The size of the relevant audience spending compared to the annual revenues of existing firms in that sector. Business operators certainly will accept any new revenues, but for them to expand an existing operation or to open a new one, they usually have to see a very significant market opportunity

- Other influential forces that cross the arts venue’s impact paths and either facilitate or hinder the ability of art audience expenditures to stimulate business expansion and attraction.

Below, I will try to do this when looking at arts audience expenditures for overnight lodgings and restaurants. For reasons of space, I will not look at the retail related expenditures, except to note here that:

- They are relatively small, especially for apparel.

- The gifts expenditures have fewer and fewer stores to capture them as music and book sales have gone strongly to the Internet.

- The retail industry is in turmoil.

- Again, note that arts audience expenditures only go to a few types of retailers.

The analysis looks at six arts venues that are located in towns with populations under 17,000. I wrote about four of them in my last article: The Weston Theater Playhouse, The Brandywine River Valley Museum, The Norman Rockwell Museum and Goodspeed Musicals. Being added are the Paramount Theater in Rutland, VT and the Country Gate Theater in Belvidere, NJ. I used averages of AftA estimates of arts audience expenditures in the 23 study areas described above to estimate those generated by these six arts venues. They are probably on the high side as a result. The data on the number of firms in a town should be treated with caution. I used Google and Yelp to make these estimates. I have more confidence in the magnitudes of these estimates than in the precise numbers. Also, I used census data on “accommodations” because that category included operations such as hostels and B&Bs as well as hotels and motels. From here on, I’ll use “hotel” to cover both.

Hotels. Most hotel chains and developers, today, shy away from smaller towns and only see as viable projects with lots of rooms that cost tens of millions of dollars. Attracting a hotel developer/chain to small towns is not impossible, but it certainly can be very, very difficult. There is, for example, at least one chain, with 90+ locations, that specializes in smaller towns. Rehabbing an existing old hotel is never cheap and seldom easy. Whatever the size of the arts audience lodgings expenditures, converting them into new or renewed hotels is unlikely to be either quick or easy.

In the above table, notice that all of the towns have accommodation operations, even those with the lowest populations. Several of these communities have operations that call themselves small hotels or inns, with as many rooms as what others might call a large B&B. However, they often also have fairly popular restaurants and bars. Stockbridge, MA, and Weston, VT, are examples. These operations can capture some arts audience meals and drinks expenditures as well as some of those for lodgings.

The audience expenditure dollars for overnight lodgings vary being between 2% and 29% of the average accommodation establishment in the counties in which these six communities are situated. They account for less than one percent of all accommodations revenues in each county. A new hotel in these communities obviously would need to tap other market segments and would not be able to capture all of the audience expenditures. Arts audience lodging expenditures could be important, if only minority revenue sources, for a hotel with average revenues in four of these towns: East Haddam, CT; Rutland, VT; Stockbridge, MA and Chadds Ford, PA. In these communities, it is probable that existing accommodation establishments are benefiting to some unknown, but a probably significant degree, from the local arts organization audience expenditures. They probably do not in Belvidere and Rutland — and for contrasting reasons. My estimate of the maximum that the County Gate Theater’s audience might spend on overnight lodgings is just $11,070. That is far too small to produce any appreciable effect on either the downtown’s hotel or the town’s highway motel. Competition in the county is relatively sparse – only 14 competitors – so the local operations would have a stronger chance of winning a good share of larger audience lodging expenditures.

The situation in Downtown Rutland (population 16,495) merits a still closer look. It demonstrates the importance that other factors can play in determining if an arts audience’s expenditures will be captured and influence business operators in a downtown. Downtown Rutland has not had a major hotel since 1980 (it has a small hiking hostel), though the city has about two million tourists passing through it annually and several motels opened in the nearby Routes 4/7 corridor. For over 40 years community leaders have tried to attract a hotel developer for “The Pit,” a vacant site where the Berwick Hotel once sat. That site is across the street from the restored Paramount Theater. A recent effort to develop a 128-room, $18 million hotel notably selected another site in the downtown. However, that proposal has been on the table for several years now. Market support, according to a consultant’s report, is not a problem. Another report suggests the project stalled because of city tax rates. I suspect other factors may be involved such as city financial incentives or the need to relocate a bank drive–through that is now on part of the site. Without that hotel, there is no downtown entity that can capture a meaningful share of the Paramount’s audience lodging expenditures

The Paramount’s annual audience of 50,000 probably throws off (based on AftA estimates) about $184,000 in expenditures for overnight lodgings. That’s only about 30% of the average annual sales of hotels/motels in Rutland County. The Paramount’s audience, by itself, plainly cannot provide the needed market support for such a hotel. It might provide some market support, but the amount would also strongly depend on the hotel’s ability to compete with the county’s other 61 hotels/motels. The stalled Rutland hotel project shows that other forces can determine whether an arts venue’s audience expenditures can have clear paths for having positive impacts on downtown businesses.

Some smaller communities with strong scenic and leisure activity assets might attract a large resort hotel, e.g., Crested Butte, CO. Otherwise, nurturing B&Bs, Airbnb units and campgrounds might be better-calibrated facilities for capturing arts generated overnight stay expenditures. This is another good example of how the existence and attributes of an impact receiver can make a big difference in determining whether any impact will be made, as well as its magnitude.

The Brandywine River Valley Museum is located in Delaware County. Of the six counties in the table, Delaware is by far the largest with a population of 558,979. It also has some of the most prestigious educational institutions in the nation: Swarthmore, Haverford, Bryn Mawr and Villanova. These factors will also generate substantial demand for hotel rooms – and restaurant tables.

Restaurants. As noted above, whether the eateries in these smaller towns can capture the arts audience expenditures for meals depends a lot on their characteristics and those of their immediate environs. It’s also important to realize that the restaurant industry today is in the midst of a significant upheaval, if not quite to the extent seen in the retail industry (see for example https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/06/its-the-golden-age-of-restaurants-in-america/530955/). Consumer preferences are changing and restaurant operators are trying desperately to keep up with them. This creates more uncertainty about any analysis of an arts audience’s impacts on restaurants.

Nevertheless, the data in the above table suggest that even in these smaller towns, arts audience expenditures may be of considerable interest to local restaurant operators.

All of these towns have at least six eateries, four of them have 14+. Furthermore, four of them have sufficient audience expenditures to support between 1.0 and 2.8 restaurants with annual revenues equal to their county’s average. Also, in those four towns, if each eatery is allotted an equal share of the audience meals dollars, they would average earning between $28,333 and $291,429 from this source. In Chadds Ford, that revenue share, $291,429, is itself above what is minimally needed to support a small 1,500 square foot eatery, $275,000. Stockbridge’s share is about 75% of that number. Those revenue shares would be 16%, 6% 39% and 40% of the average restaurant revenues in their counties. It seems reasonable to conclude that at least restaurant owners are likely to pay attention to these arts venue audiences. Indeed, many are probably now capturing significant revenues from them.

Belvidere is where restaurant operators are less likely to pay attention to its theater’s audience. Only $30,600 in audience meals and drinks expenditures are generated there. Proposals have appeared to build several hundred units of market rate housing in this community. Such units are likely to be predominantly occupied by households with fairly affluent incomes such as those presented in the above table. Just 25 new units occupied would provide three to five times more potential revenue dollars for local restaurants than the theater’s audience now can. Larger numbers of units might have some benefits for the theater. It may increase demand for tickets to its performances. It may also stimulate the improvement of local restaurants, which then enables them to make more theater goers happy and the eateries can capture more of the audiences’ meal expenditures.

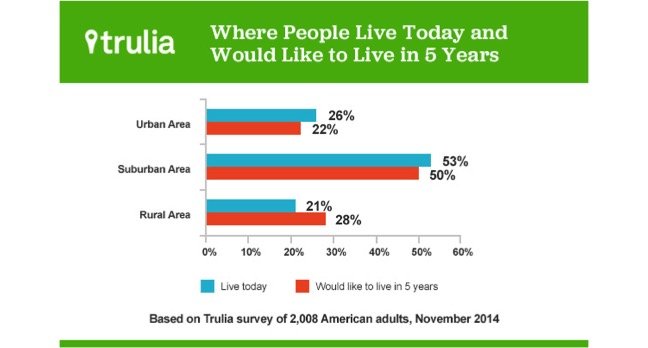

Of course, the expenditures of these new households would go to shops across the whole gamut of retail and professional service functions and have far, far greater potential impacts on the local business community than any arts venue can. Downtowners in smaller cities should also explore housing as a revitalization engine. Conversely, the presence of arts venues can make a community a much more attractive place to live and help bring in more residents.

Weston, VT, also appears to be a place where its arts audience probably will not attract much attention from restaurant operators. However, it is special because the Playhouse audience’s spending for meals is condensed into 10 weeks during the summer. The $204,000 spent during that period may have the impact of $800,000 spent elsewhere over 12 months. As a result, local restaurants might pay a lot more attention than the sales potential numbers alone might suggest. These expenditures also come at a time when there are no “leaf peepers” or skiers — the prime market segments for Windsor County’s hospitality operations. This shows just how important the timing of audience expenditures can be.

More Studies On The Arts’ Impacts On Downtown Real Estate Should Be Done — and Can Be Done — in Small Downtowns.

Any study of a downtown arts venue’s impacts should have a real estate component.

As noted above, many parks are venues for performing arts events. Some also exhibit art or hold crafts fairs. Their ability to impact on nearby property values has been well-established since Olmstead did so for Central Park. Some of the research done on parks has employed techniques and produced findings that should be of considerable interest to those analyzing the impacts of arts venues. Studies done on Bryant Park and Millennial Park in downtown Chicago, are two good examples.

Some interesting research, done over the past decade or so, has been very sophisticated methodologically. These studies recognize that impacts occur in a multi-causal world, using statistical techniques and relevant data that enabled them to estimate the individual impacts of several variables. Two of them are:

- Landauer Valuation & Advisory’s study of Bryant Park’s impact on nearby office building rents and property values(4).They used a multi-regression statistical model to isolate the park’s impact compared with several other relevant variables. They also incorporated personal interviews with 29 appraisers, commercial brokers, and building representatives.

- Stephen C. Sheppard and his team at Williams College’s Center for Creative Community Development did a landmark comprehensive study on the impacts of MASS MoCA, including those on property values in North Adams, MA. They also studied the impacts of the Kenosha Museum in WI on that town’s property values (5).

Unfortunately, as Sheppard has acknowledged, the methodologies used are relatively expensive. Today, only organizations with large budgets are likely to use them.

There is a real need for less expensive, yet similarly, effective research techniques to be developed to study the impacts of arts venues on downtown properties. In smaller towns, fewer properties may make such an analysis easier, if property records are computerized and properly kept.

Some attempts to do so have been conceptually muddled. For example, one study selected an inappropriate geographic area to use as a comparable to establish the impacts of a PAC on its neighborhood. Others mistakenly take the total cost of a new building as the dollar expression of an arts venue’s impact on it – disregarding the possibility of other impacters or that the size and cost of the building might have been heavily influenced by the space requirements of its future anchor tenant.

In smaller downtowns, simple real estate research techniques may be ample for meeting the information needs of their leaders and stakeholders. To begin with, many of these small downtowns will not contain a huge number of properties, so data collection may be easier. In the larger small downtowns, selecting a subarea around the existing or proposed arts venue might also reduce costs and simplify the research. Also, for these downtowners, impact findings that state the magnitudes, not in metric terms, e.g., numbers of dollars or jobs, but through the many ordinary ordinal quantifiers contained in our everyday language (e.g., more-less, strong-weak, large-small, etc.) may not be optimal, but still very sufficient. Though they may not be able to quantify in terms of dollars how an existing arts venue has affected the rents, occupancy rates and property values of nearby properties, they can establish if there have been positive or negative effects. Collecting before and after data on these variables should be feasible. (Landlords and municipal data can provide a lot of the most important data.) Visual inspections of the properties from photographs from previous years and field trips to see current conditions can also provide important clues. Most importantly, interviewing local landlords and a convened panel of experts who really know the downtown’s properties can provide very useful insights on those impacts and whether they have been small or large, important or unimportant, etc.

As for a proposed arts venue, finding comparable projects in comparable downtowns probably will provide useful insights. However, again, finding that comparable may not be easy, so it’s best to be prepared for that.

If the impact analyst can develop reasonable estimates of how much residential, retail, restaurant and hotel space the new art venue might generate that can be turned into estimates of how it would increase demand for those spaces, then asking local landlords, developers, bankers and savvy real estate brokers how they would respond to that increased demand might be instructive in a directional manner, but certainly not predictive with any precision. But, then, you can’t make wine from rocks.

The biggest lesson I have learned from the impact studies done on the Lincoln Center for Performing Arts is the importance of looking at how arts venues affect the desirability of their surrounding neighborhoods as places to live. Restaurant and retail growth usually follow residential growth, as does increased pedestrian activity. An intercept or online survey of local residents to determine how an existing arts venue has affected how much they like living in that town or how much a new venue would do so, can provide very strategically important information. In these small downtowns, the fate of the businesses operating in them as well as residential property values is heavily tied to how many people live nearby and the personal and financial resources they have. Residential development is a key even for smaller downtowns. The degree that arts venues can contribute to it is an important impact path to know about. It also can be part of a quality of life business recruitment strategy.

How the Downtown Works

Dead pedestrian spaces, traffic congestion, improved physical appearance, pedestrian traffic levels, improved walkability and many more aspects of how your downtown works can be impacted by any new venue, including those related to the arts. As a downtown’s Central Social District functions grow in importance, so do those issues. Below are some of the kinds of information I would try to collect and some ideas about where to find them.

The Information Needed (And How To Get It):

- Arts organization spending by category and identification of district vendors. (Its annual budget and IRS 990 Form; interviews with organization staff or from its vendor list).

- The number of events. (From organization calendar.)

- When during the day the events are held. (From the organization’s calendar.)

- The number of people attending the events: annual total, event average, time of day average. (From organization records.)

- The arts event related audience expenditures (ideally from an intercept survey at the arts organization’s events; otherwise ballpark estimates based on comparable communities.)

- Attitudes and perceptions of downtown users about how downtown arts venues and the town’s desirability as a residential location (Intercept and online surveys.)

- Building Improvements: new, major rehab or addition, minor rehab or addition. (Visual inspections, organization reports, review of photos, review by architects; surveys of downtown residential and daytime populations.)

- Data on rents, commercial and residential in downtown buildings (Landlords, realtors.)

- Increased auto traffic and congestion. (Traffic counts, field inspections, consultant reports.)

- Parking: increased demand, spaces added. (Parking agency and studies.)

- Mass transit: increased demand and use. (Transit agency.)

- Public spaces added: if so, is it well-activated or stagnant.

- Dead spaces added. (Field inspections and distance measurements made with a “wheelie.”)

- Increased pedestrian activity and congestion points. (Counts and field observations.)

- Increased need for police and sanitation services. (City departments.)

The Bottom Line

Downtowners in smaller communities who focus on making the arts the chief or only engine for revitalizing their downtown are likely to be disappointed. The range and depth of the impacts arts venues have are insufficient by themselves to spark lots of other businesses to prosper or grow. They often themselves need other strong downtown actors and/or favorable conditions to prosper.

The arts, however, have a value in and of themselves. We should want arts venues basically because of their intrinsic value and how their programs and holdings inform and celebrate the human condition. True, they also can make important contributions to a small downtown’s economy. They can be a valuable component in a comprehensive downtown revitalization strategy. Growing arts venues as part of a larger effort to grow the downtown’s Central Social District functions and to increase the community’s attractiveness as a residential location can succeed because there are strong impact linkages among them. Together, they have true synergies and, for a change, their pathways are fairly well known.

Do not, however, give the arts the role of becoming a downtown’s economic savior. More often than not, that will be a bridge too far.

ENDNOTES

1) See: Baker Tilly. “Restaurant Benchmarks: How does your restaurant compare to the industry standard?” http://www.bakertilly.com/uploads/restaurant-benchmarking.pdf

2) Americans for the Arts. ARTS & ECONOMIC PROSPERITY 5: THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF NONPROFIT ARTS & CULTURAL ORGANIZATIONS & THEIR AUDIENCES. http://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/research-studies-publications/arts-economic-prosperity-iv

3) Ashley Lutz. “Here’s how much it costs to eat at 22 chain restaurants.” Business Insider, March 23, 2015. http://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-it-costs-to-eat-at-resaurants-2015-3

4) Landauer Valuation & Advisory, “Valuation Study of: Bryant Park Business Improvement District.” New York, NY, December 2014

5) Stephen Sheppard, “Measuring the impact of culture using hedonic analysis.” Center for Creative Community Development, October 2010, pp.28. See also: Stephen C. Sheppard, Kay Oehler, Blair Benjamin and Ari Kessler. “Culture and Revitalization: The Economic Effects of MASS MoCA on its Community.” C-3-D Report NA3, 2006, pp.17.