By N. David Milder

Introduction

This article is a follow up to:

- “Some Key Aspects of the New Normal for Downtowns: some emerging challenges” which can be found at: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2013/12/some-key-aspects-of-the-new-normal-for-downtowns-some-emerging-challenges

- “The Changes in the Retail Industry That Are Impacting Our Downtowns” which can be found at: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2016/09/the-changes-in-the-retail-industry-that-are-impacting-our-downtowns

- “How Smaller Rural Downtowns Are Faring Under the New Normal’s New Retailing“ which can be found at: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2016/10/how-smaller-rural-downtowns-are-faring-under-the-new-normals-new-retailing

- “Downtown Retailing in Smaller Rural Regional Centers Under the New Normal” which can be found at: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2016/10/downtown-retailing-in-smaller-rural-regional-centers-under-the-new-normal

Following the path of the last article, it also will explore how the changes in the nation’s retailing are manifesting themselves in different types of downtowns. The changes this article will look at again are:

- The emergence of the deliberate consumer

- Reduced demand for retail spaces

- The growing strength of e-commerce

- The continued growth of a broadly defined “value” category of retailers

- The decline of traditional department stores and traditional specialty retailers

- The uneven opportunities for small merchants

This time the focus will be on suburban downtowns that have the kind of prestigious retail chains that many downtown leaders, in both the suburbs and cities, very often crave or covet: Gap, Talbots, Starbucks, Victoria’s Secret, Williams Sonoma, etc. I will focus attention on a few of these downtowns that I know well, because I have visited them and/or previously done research about them. Between 1994 and 2000, I did several projects for the Englewood EDC and worked closely with its director, Peter Beronio. I’ve done one small assignment for Westfield’s Main Street program but, I researched in-depth the downtown’s retailing for two assignments I did for the neighboring town of Cranford. I’ve continued to visit Westfield over the years, because I found it to be so successful and interesting. For eight straight years I visited Wellesley, MA, about four times a year as my daughters attended college in the area. I last visited in 2008 and have tried to keep pace with its retail mix since then online. I will then compare these downtowns to downtown Morristown. In contrast, that district depends on successful smaller retailers whose prospects are enhanced by the downtown’s strong Central Social District assets. All four downtowns are among my favorites because of their scale, walkability and attractive establishments that provide food and drink.

The trophy retail downtowns, to varying degrees, are now being wounded by the very retailers that have previously made them strong: the traditional specialty retail chains. The strength and character of the demand for local retail space consequently has changed very significantly – not only do the landlords in these downtowns need to find different tenants, but they also must provide different kinds of spaces to accommodate them. The changing strength and presence of the major retail chains are also altering the array of problems local independent merchants have to face.

I suggest that many of the conclusions and observations I make below should be treated as hypotheses, since I cannot claim that they are based on a rigorous, wide reaching, systematic research effort. However, I hope that the discussion below convinces readers that I have done enough number crunching, field visits, personal interviews and analytical thinking to warrant my observations and conclusions being deemed worthy of serious attention and consideration.

Many of the old rules of the retail game are still in effect. Bad urban design and the lack of appropriate spaces can still thwart downtown retail health and growth. Also, the dynamics of constructive economic destruction can still mean that when some retailers falter in a market, others have the opportunity to enter and compete for that lost market share. When conditions change, downtowns need to develop appropriate adaptive responses – this is the biggest challenge now facing downtowns of this ilk.

Some Background on These Communities

Wellesley, MA. On my first trip to Wellesley in the early 1980s, as I walked along Central Street, I was first grabbed by a very attractive aroma that I traced to one of George Howell’s Coffee Connection locations. Inside, they were roasting coffees that smelled delicious and tasting them proved that they were. Howell is one of the best coffee bean selectors and roasters in the nation. He later sold his chain to Starbucks and his Wellesley location is today a Starbucks. Also, noted chef Ming Tsai has his Blue Ginger restaurant in this downtown.

After that terrific cup of coffee, I then quickly noticed that the downtown had an attractive scale, was very walkable and was filled with a mix of very attractive independent retailers, small regional chains and highly coveted national chains. I had never seen before so many prestigious retail chains in one suburban downtown.

Wellesley is most definitely a college town, but not a normal one, because it is also a very wealthy residential suburb of Boston and adjacent to a number of other wealthy suburbs. As can be seen in the above table, the average household income in Wellesley is about $237,462; for Wellesley and its abutting towns, the average household income is $188,239. These numbers are substantially higher than those for Westfield and Englewood, that, in turn, are also well above those for most other suburban communities. This affluence is reflected in the median value of owner-occupied homes in Wellesley, $914,000.

Wellesley College with its 2,344 students, has a definite impact on this downtown’s eateries and drinking establishments. The campus is within very easy walking distance of the downtown’s commercial core. While the research results I’ve reviewed recently suggest that college students nationally have significantly less discretionary funds available to them than they did in years past because of much higher costs for tuition, board and fees, my strong guess is that this is far less the case for Wellesley College students. For one thing, their costs for tuition, room, board and fees total $61,088 per year and only affluent households can afford those expenditures. While many of the students will get financial assistance, many of them will still come from households that have above average household incomes. Babson College, known for its entrepreneurship education, with about 3,000 students, is also in this town. It costs about $62,440/yr for a boarding student to attend. Additionally, within an easy walk of the downtown core is the Dana Hall School with its 356 female students in grades 9-12. Its annual costs are $40,116 for day students and $53,211 for boarding students.

Wellesley College provides many cultural-entertainment facilities: a movie theater, legitimate theater and art museum.

The strange thing is that so few of the retailers seem to focus on the students. Most of the apparel shops, for example, have been those that target an older demographic. The students seem more likely to shop in malls in Natick and Chestnut Hill.

Entrance to the Wellesley College Campus on Central Street, downtown Wellesley.

On Central Street in downtown Wellesley, this is one of the largest Talbot’s stores I’ve ever been to.

According to the Census Bureau’s On-the-Map dataset, Wellesley has a significant number of people working there, with 16,813 having fulltime jobs. The presence of this many college students and employees means that there is a significant local daytime population for merchants to tap.

Total annual retail sales in Wellesley are fairly robust, about $432 million. The Natick Mall is 5.5 miles away, The Shops at Chestnut Hill are 7.7 miles away. Both remain powerful, with impressive lists of high quality retail tenants. They are among the small percentage of malls that are doing really well under the new normal and in sharp contrast to the retail malls in Rutland, VT, and Scottsbluff, NE, that I discussed in my last article.

There is a downtown merchants association, but the development of this district does not appear to have been impacted by any EDO or revitalization strategy. That speaks loudly about the strength of the community’s economic development related assets and healthy market forces.

Englewood, NJ. Of these three communities, Englewood is the one I know best having done many assignments there from 1994 to 2000.

Englewood is the most diverse of the three communities. About 45% of its population is white only. In comparison, both Westfield and Wellesley are over 85% white only.

Englewood has a fairly high average household income, $115,679, and its trade area’s is $131,256. Its most affluent shoppers do not reside in the city, but in other parts of its trade area. However, its median income, at $73,249, is just 1.6% higher than that of the state. This points out that a lot of people, mostly of color, with relatively modest incomes, live near the downtown. However, Englewood also has had as residents some very successful people of color, such as Dizzy Gillespie, Eddie Murphy, George Benson, Nancy Wilson and Patrick Ewing.

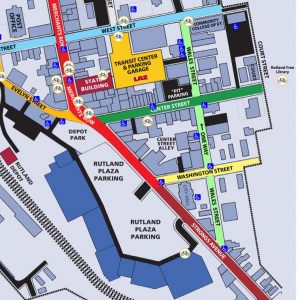

This income divide was reflected for many years in how the downtown worked. An active railroad track ran through the heart of the downtown and “the other side of the tracks” along Palisade Avenue (the primary retail corridor) was a very meaningful term. The east side had many successful boutique shops and restaurants that successfully attracted upscale shoppers living up the hill in Englewood as well as from Tenafly, Alpine, Closter, Haworth, etc., (see the above map). The city has long had a sizeable daytime workforce, recently totaling about 14,708 fulltime jobs, but it’s eateries and merchants can also easily tap the 8,437 workers employed in major corporate offices located nearby on Rte 9W in Englewood Cliffs.

The west side of the downtown, however, was falling into increasing decline. Armory Street became the scene of much drug use and sale as well as prostitution.

Entrance to Palisade Court in downtown Englewood

Group USA and The Children’s Place on West Palisade Avenue. Both are now gone.

Around 1991, the city brought in Treeco, a local developer and land owner, to build an in-downtown shopping center, Palisade Court (see photo above). It was and is anchored by a large (now 60,000 SF) supermarket. While that center was successful, it failed to help revitalize the shops just steps away on West Palisade Avenue, because it was so inward looking. However, by 1996, a surge of new, highly desirable retail chains began to appear on East Palisade Avenue, e.g., Ann Taylor, Nine West and Starbucks. Within a few years the problems on Armory Street were cleared. Soon thereafter Group USA opened in its own new building on West Palisade, bringing in Mikasa with it. Group USA also brought in The Children’s Place, when Mikasa left (see photo above). Treeco, too, was actively recruiting quality new retailers and developing a substantial number of housing units. It would bring in Victoria’s Secret and New York & Company. By 2000, downtown Englewood was the success story of downtown revitalization in New Jersey, and leaders in many other communities wanted to emulate its achievements. It’s success was noted frequently in the media, including several articles in The New York Times.

The city of Englewood has very strong total retail sales, over $1 billion a year. A lot of that comes from its 11 major automobile dealerships, with most of them selling high value brands — such as Mercedes Benz, Lexus, Infiniti, Porche and Audi. They are strong regional draws. However, Englewood’s retailers potentially must contend with powerful malls: the Shops at Riverside is 4.3 miles away, the Outlets at Bergen Town Center is 6.1 miles away and the Garden State Plaza is 7.3 miles away. All of these malls were upgraded in recent years.

During its most successful years of downtown revitalization, Englewood had an extremely effective economic development team that included its mayor, the city manage, its community services director, its planner and the president of the city council. They were able to get the sustained support of most city council members and to develop consensus among these key decision makers about the strategy to pursue and the projects to build. Today, that team and the consensus about strategy and projects appear to be gone.

This downtown has the Bergen PAC, which was formally the John Harms Center. It draws a considerable audience to its many events. The downtown has no movie theater. Its restaurants have been strong, but now seem to be in flux. It also lacks a well-activated and popular public space.

The downtown’s retail revitalization has greatly benefited from having a capable developer, Treeco, and a very savvy commercial broker, the Greco Realty Group LLC, located in the city.

Westfield, NJ. I initially visited this downtown around 1995 or 1996 to do a small assignment for its Main Street program. I was then impressed, because I found another of George Howell’s Coffee Connections there. Ever since, when I think of one of these two towns, I inevitably also think of the other. A year or two later, I had to take an in-depth look at Westfield’s retailers as I researched for a retail revitalization strategy DANTH was developing for the Cranford Downtown Management Corporation. By then Starbucks had replaced the Coffee Connection, and the downtown had a growing number of important retail chains. The presence of a real department store, Lord & Taylor, had long given this downtown a key recruitment asset. Some of those retailers were regional chains that fell victim of the dot.com economic downturn, but they were soon replaced by a trend of more and more high quality specialty retail chains.

The Gap in downtown Westfield. This chain is harder and harder to find in suburban downtowns – photo from Google Maps

By around 2007, when I again had to study downtown Westfield’s retailers. Its cluster of highly regarded national retail chains reminded me of a lifestyle mall, but one without a common ownership.

Westfield long has had lovely homes and great schools. Recently, it acquired a direct commuter rail connection to Manhattan. Consequently, it is an even more highly desirable residential community than ever before. It’s population is well educated – 66.4% have a B.A. degree or higher. The average household income is $187,669/yr, and the average for Westfield and it surrounding communities together is about $152,000/yr. Westfield’s median household income is $138,165, so a substantial majority are probably in the $100,000+ bracket. That affluence is reflected in the median value of owner occupied residences in Westfield, $653,900.

Ann Taylor in downtown Westfield. In the 1990s, this chain stood out for its interest in suburban downtown locations. Today, it looks very closely at such locations.

One thing that downtown leaders elsewhere should take away from this discussion of Wellesley, Englewood and Westfield is that if they want to attract “trophy retailers,” they better have an awful lot of households with incomes above $100,000/year – over $200,000 would be better still.

Total annual retail sales in Westfield is the lowest of the three communities being looked at in this article, at $262,436,000/yr. Of course, over a quarter of a billion dollars in sales is far from shabby in anyone’s book. The nearest major mall, the very powerful Short Hills Mall, is about 8.9 miles, or about an 18-20 minute drive, away. There also is a substantial amount of retail strung out along the nearby Rte 22 corridor, but those retailers are not of the kind likely to compete with the ones in downtown Westfield – those in the Short Hills Mall are. On the positive side, the distance between downtown Westfield and Short Hills means that some retail chains could consider having stores in both locations. That is not the case, for instance, with Maplewood and Morristown; both have been basically shunned by major retail chains because of their proximity to Short Hills. I think that factor helps explain why Westfield attracted so many of the highly coveted specialty retail chains.

Of the three communities, Westfield has the fewest people working in the community, 9,281.

This downtown has a movie theater. It lacks a well- activated and popular downtown public space. It does have about 50 restaurants, and many are highly rated and been around for a long time. Its inventory of fast food restaurants includes a lot of today’s most popular with Millennials: e.g., Panera Bread, Chipotle, and Five Guys.

Papyrus is in all three of the downtowns under discussion.

Downtown Westfield probably has the smallest daytime population of the three communities. It has really depended on the repute of its large cluster of high quality retail chains to generate daytime customer traffic. The rents close to the strongest of these popular retail chains will be significantly higher than spaces farther away from them. Independent merchants are thus caught between wanting to be close to these strong retail attractions and having to pay the higher rents to do so.

Westfield also has benefited from having an effective local commercial brokerage community and a well-run, nationally recognized Main Street program that also manages a SID.

What Happened

As was explained earlier in this series of articles, specialty retail chains have been facing increasing competitive pressures since the end of the Great Recession. A good number have gone bankrupt. Many others are struggling, closing many stores and trying to establish a more effective online presence. Consequently, it is not surprising that these three downtown have seen the flight of many of their prized national retail chains, though to significantly varying degrees. This flight has posed a number of challenges, some old, others new. Most importantly, it poses the challenge of formulating an effective strategic response.

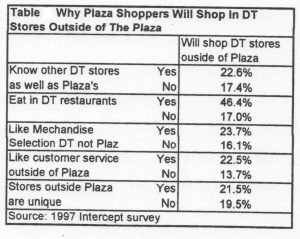

The Extent of Retail Chain Closings. The above table lists the major retail chains I could identify that are now present in each of these downtowns as well as those that have left in recent years:

- Englewood, NJ: A total of 19 major retail chains were at one time located in Englewood since 2008. Eleven, 58%, have left. Seven of the 11 sold apparel. Eight of them remain.

- Westfield, NJ. This downtown attracted a total of 34 major retail chains, of which 14, or 41%, closed. Nine of the 14 sold apparel of one kind or another. That still leaves the downtown with an impressive array of 20 national retailers that includes: Ann Taylor, Banana Republic, GAP, Lord & Taylor, Urban Outfitters, Victoria’s Secret, Williams Sonoma and Trader Joe’s.

- Wellesley, MA. Of the 17 retail chains that I was able to identify as having a downtown Wellesley location during this time period, five, or 29%, closed. Of the five, three sold apparel of some sort. 12 of the retail chains remain downtown. However, a local newspaper article provided information that suggests that in this downtown, the small independents and small chains may have been the worst hit by the new normal’s tougher environment for retailers. For example, Kaps, a four-location menswear chain, closed down. A good number independents also reportedly closed or moved to new locations that had lower rents and good proximity to the customer traffic generated by the Natick Mall.

Why They Closed. First, in absolute numbers, the more national chains a downtown had, the more it was likely to lose them: Westfield 14 of 34; Englewood 11 of 19, and Wellesley 5 of 17.

Also, in these three downtowns, the percentage of retail chain closures seems to be associated with the affluence of their potential customers. Wellesley and its surrounding towns have the most affluence, and that downtown has the lowest percentage of retail chain closures. Englewood and its trade area have the lowest household incomes of the three communities (though averaging over $100,000), and the highest percentage of chain closures. Might other downtowns, with even less affluent trade areas face even more retail chain closures? The sample size of three is admittedly miniscule, but this finding, when added to other pieces, begins to paint a picture worthy of serious consideration, if not of certain acceptance.

Tony Schilling, of Relocation Realty, is a very savvy commercial broker based in downtown Westfield. He has helped put many major retail chains in New Jersey downtowns, including several in downtown Westfield. He has been involved in the selection of 30 Chico’s store locations. He reports that the chains in downtown Westfield told him that, since the Great Recession, they saw a serious drop in customer traffic and spending. This, of course, is consistent with the Great Recession induced emergence of deliberate consumers, whose geographic presence and intensity diminishes as incomes rise.

Tony also pointed out that the situation for retail chains in downtown Englewood was probably worsened by the strengthening of the nearby malls. They not only may have taken away customers, but they also could take away retailers. For example, Gymboree closed in Englewood and opened in a nearby mall. While many malls are failing, and more are struggling, others in the best locations are adapting to the new conditions and doing quite well. The malls that these three downtowns compete with fall into that category.

Also, a few years ago, a top level executive managing the retail related business of a major national real estate brokerage firm, told me that the sales of the national retail chains in downtown Westfield were not as high as their stores in successful retail malls and that this was also true of most other suburban downtowns where they are located. This, unfortunately, means that these downtown chain stores are liable to be on the chopping block should their corporate masters face very rough waters.

A few downtown managers I’ve communicated with recently tried to explain away the closing of a retail chain in their district by stating it was a corporate problem. In my opinion, that avoids some important truths. As can be seen in the above table, few of the store closings were the result of a corporate bankruptcy. What usually has happened is that the parent corporation finds itself in serious trouble and, in trying to right itself, decides to close its poorest performing stores. The performance of that store may have something to do with the chain’s corporate strategy – e.g., its products are targeted for a market segment that is aging out, becoming fewer in number and buying less. It also could be that the demographics of the store’s trade area or its daytime popualtion have changed and have fewer of the kind of customers that a retailer is focused on. It’s essential that downtown leaders know what’s what on this score and not flippantly ascribe retail chain closures to just corporate problems.

According to Tony, many of the retail chains in downtown Westfield report that they and local independents are being badly hurt by the growth of e-commerce. Some of these chains, e.g., Chico’s, are trying to create a stronger online presence. If that is their strategy for the future, then their return to downtown locations is not likely to any significant extent. Such a return would also probably be based on significant use of a “click to brick” strategy where shoppers order online and pickup their purchase in a downtown store. In turn, that probably would reduce the retailers space requirement. Theoretically, if their sales transactions are so online driven, it could also reduce their need for prime geographic locations.

Some Important Fallouts of These Closures. Obviously, when retail chains close, vacancies are created. If a good number of these closings cluster in time and geography, the problem can be very serious indeed. Another problematic aspect of such a situation is that, unless another chain with a large space requirement can be found, it probably will be too large and its rent will be too high for most independents to lease.

Moreover, according to Tony Schilling, the retail chains that are now looking for new downtown locations want much smaller spaces than years ago: 1,800 SF to 2,500 SF instead of 5,000 SF to 7,500 SF. This creates a serious problem for landlords of the larger spaces that will need to be divided, with the smaller spaces being leased separately. This all jives with reports on the national level that retail chains are looking for smaller spaces, and I find it enlightening to see what that means on a local level. For downtown Westfield, and its landlords it also may mean that a significant amount of today’s retail space will have to be converted to other uses.

Because the major retail chains are such important traffic generators, when their numbers are greatly reduced that makes the downtown a less viable location for the remaining chains as well as for small merchants. That appears to have happened in Englewood according to the owner of a small retail chain with a store in that downtown, and Tony Schilling says it also has happened in Westfield. I think downtown Wellesley has been better able to absorb its closures shock, with the least reduction in daytime customer visits, because it had fewer closures and the district has so many other assets going for it.

The entry of major retail chains into a downtown usually is associated with a significant rise in retail rents. Tony Schilling reports that, at least in downtown Westfield, the reverse can also occur. According to him, retail rents there are now about 20% lower than they were before the Great Recession and the ensuing flight of many retail chains.

For small merchants, the situation is a two edged sword: they may find they are paying lower rents, but the major retail chains are pulling fewer shoppers into the downtown.

How Can Such Downtowns Successfully Adapt to the New Retail Conditions?

In my opinion, this is now a key question for downtown Englewood and downtown Westfield. The following are some broad strategic options they might consider.

- Keep going after traditional chains. If downtown leaders do nothing, this is their default strategy, which now is metaphorically akin to continually butting their heads against a stone wall.

- Go after emerging and growing chains or those that like smaller cities. One of the most interesting things I have recently observed in my research and travels through NY, NJ, MA, VT and CT is the number of small chains that have recently opened downtown stores. Some of them that opened in Westfield and Englewood are listed in the above table at the very bottom. Additionally, there are many retail chains that feel quite comfortable in cities with populations of 15,000 to 35,000, such as Maurice’s and Francesca’s, though they often tend to prefer shopping center locations over those in downtowns.

- Develop strong retail niches. Back in the early 1990s, downtown Englewood had a very strong niche of women’s apparel boutiques clustered closely together on North Dean Street and West Palisade Avenue. Its success helped convince the national chains about the viability of locations in downtown Englewood. Today, after many of its national apparel chains have closed, a rejuvenated women’s apparel niche has emerged, primarily in the same Dean Street and West Palisade area. It now has 24 boutiques, five of which belong to small chains. Savvy local commercial brokers are recruiting to this niche. A niche marketing program run by the Englewood EDC would probably have a high ROI. Other downtowns should consciously try to develop such niches. They can attract considerable customer traffic that helps keep the downtown active, retail sales flowing, property values strong and town tax revenues from declining.

- Economic gardening to seed and nurture high quality small independent retailers. This is an approach that the vast majority of downtown EDOs run quickly away from, because it is very tough to execute and hard to get a meaningful ROI. However, over the recent years, as I’ve tried to wrestle with how downtowns in rural and suburban areas can leverage growing contingent worker workforces, I’ve become convinced that they need to tap some meaningful economic gardening capability, whether it is in-house or in another organization. Perhaps a very focused problem-solving approach would make them more effective and easier to operate. For example, of the 24 boutiques in Englewood’s women’s apparel niche, less than one-third had any meaningful internet presence. In general, many non-Millennial retailers still need to become more agile on the Internet and able to use the social media effectively. A program to help them could have considerable impact.

- Develop a “quality of life” retail recruitment program. I hope to write an article about this soon. On my recent trip to VT, I found two retailers who had moved to the Rutland area because they liked its quality of life and then opened women’s apparel stores in its downtown. Years back, I met the former road manager of Pink Floyd, who had opened a housewares store in downtown Woodstock and then a restaurant in downtown Rutland. Around then, I also met in Rutland three people born and raised in the NYC metro area, but now lived in Vermont, while having successful telecommunications enabled careers managing an investment fund, being a computer graphics specialist and being a business consultant. I’ve read about a chef who went to meet his new in-laws to be, then living in a retirement community west of Phoenix, and he liked the area so much that he then decided to stay and open a restaurant there. I’ve also read about creatives living in Brooklyn, NY, who started to summer in the Catskill Mountains and then opened hotels, restaurants and shops up there. As Phil Burgess, president of the Annapolis Institute, has noted, lots of folks once they pass 50 years of age “reboot” their lives and careers. I am confident that rebooters are also moving to our suburbs that offer a high quality of life. Some may also want to open a shop or a restaurant.

- Accept the potential economic value of “pamper niches” and leverage them. DANTH,Inc has found that pamper niches composed of hair and nail salons, spas, martial arts studios, yoga and Pilates studios, and gyms were important components of the street level business mixes in such diverse places as downtown Beverly Hills, CA and Bayonne, NJ. They attracted lot of patrons with money to spend and their shops do not create pedestrian discontinuities. Too many downtown leaders still have rather snobbish attitudes towards operations in this niche. The reality is that, in many downtowns, pamper niche operations are filling storefronts vacated by retailers. Sometimes, it’s better to try to leverage them than opposing them.

- Go after the value retailers as downtown Rutland did, but be sure to take care of key urban design issues. Some retailers are doing quite well these days. They are the “off-pricers” such as TJ Maxx and its sister brands, Ross Dresses, Stein Mart and Century 21 department stores. Downtown Rutland showed that having them and big box retailers can produce significant positive benefits for small merchants. However, that positive impact could have been far greater, if the Rutland Plaza project has been designed to be better integrated into the downtown core. That would have allowed local merchants to win a lot more cross-shopping from the Plaza’s patrons, while maintaining the downtown’s walkability.

- Reduce the strategic emphasis on retail. Instead develop and strengthen central social district (CSD) entities. In my 40 years of trying to help downtowns revitalize, I cannot count how often local political and community leaders wanted, more than anything else, strong retail to appear in the form of new department stores and/or a cluster of national chain stores. However, the truth of the matter was that few of these downtowns ever before had the type of retail they were aspiring to. Perhaps, in their “Golden Age,” they had had a small local department store and some well-known and well-regarded independent operators, that socio-economic forces had recently weakened, but very, very few had a branch of a major national department store chain or scads of national specialty retail chain stores. The latter did not even exist to any large degree during those hallowed golden years. This suggests that a vibrant, popular and economically healthy downtown does not equate with just an overwhelmingly strong retail base, but that a number of other factors may be as or even more important to a downtown’s success. Indeed, it even can be argued that, especially today, the health of a downtown’s retailing is more and more dependent on the strength of these other factors. Today, in downtowns across the nation and in communities of all sizes, CSD functions are increasingly important to their sense of vibrancy, economic well-being and municipal tax revenues. CSD functions facilitate people coming downtown to have enjoyable experiences with their friends and relatives or with new people that they meet there. Entities that perform CSD functions are wide ranging: e.g., vibrant and popular public spaces, libraries, churches, senior centers, community centers, restaurants, watering holes, hotels, entertainment and cultural venues, downtown residential units, etc. See: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2016/02/central-social-districts

Downtown Morristown. This district is a great example of a strong CSD and its importance. Although the town has annual retail sales around $520 million, it has not attracted anywhere near the number of prestigious national retail chains that have located in Englewood, Wellesley and Westfield. For years a former department store stood vacant. In the early 1990s, there was a strong feeling among community leaders that the downtown was in decline. Making matters worse was the fact that this downtown was surrounded by a very large amount of competing retail. The very powerful Short Hills Mall is close enough that any chain located there cannot be located in Morristown. Back in 2010, I came up with a very long list of specialty retail chains and noted their presence and distance from downtown Morristown. Everyone one of them was within a distance that would mean a new Morristown location would cannibalize sales from their nearby existing store.

Today, this downtown is vibrant, attractive and often cited as a model for suburban downtown revitalization. Morristown does not have a large population, about 18,500, and its median household income, around $76,000,is only slightly above that of the state. However, its primary trade area had a population in 2010 of roughly 99,000 and a median household income near $122,000. Its total trade area’s population was over 220,000, with income levels similar to that of the primary trade area. About 61% of the primary trade area’s households have incomes of $100,000+. Almost 60% of the trade area’s residents have a B.A, degree or higher. An even stronger retail development asset is downtown Morristown’s daytime population. There are about 23,000 fulltime jobs in Morristown. Most impressively, the downtown has attracted 1,500+ new market rate residential units It also has 77 eateries and watering holes with combined sales of $79 million+/yr. Its Community Theater has about 230 performances annually with a reported attendance of 200,000. Its 10 screen cinema has an attendance estimated at 360,000/yr. The district’s three major hotels have an estimated 196,000 hotel guest days/yr. The Morristown Green is the venue for many major events that attract crowds of people downtown. DANTH’s estimates that the downtown spending potential of nearby office workers, new residents and high school students totals over $132.9 million/yr and that the hotel guests probably add another $9 million just for their restaurant expenditures.

Since so many of the specialty retail chains in Englewood, Wellesley and Westfield sold apparel, it’s interesting to look at the size and composition of downtown Morristown’s apparel niche. It has 23 stores in a broadly defined apparel niche that includes women’s clothing, but also menswear, 2 bridal shops, uniform and tuxedo shops, three national chains and three small regional chains. This diversity makes it less vulnerable to industry and national economic vicissitudes. Two of the national retailers, Athleta and Jos. A. Bank, are also found in one or more of the three other downtowns under discussion. However, the Century 21 department store in downtown Morristown is of special interest because it is a high end “off-price” operation. This is one of the kinds of retailing that is now doing well nationally. Century 21 also shows that such a large store can be inserted into a downtown without disrupting its walkability or attractiveness, if the appropriately sized space already exists – or can be developed.

© Unauthorized use is prohibited. Excerpts may be used, but only if expressed permission has been obtained from the author, N. David Milder.

Women’s Apparel Shop in Downtown Great Barrington, MA

Women’s Apparel Shop in Downtown Great Barrington, MA