By N. David Milder

Introduction

A key facet of the New Normal for Our Downtowns is that many of the most important challenges they now face result from their successful growth and increased popularity — not from their failures. Nowhere is that more evident than with the issues of traffic and pedestrian congestion. Meeting those challenges probably means that many of our downtowns will have to develop and operate in new ways. Many observers believe the changeover to autonomous vehicles will have enormous positive impacts on how many of our downtowns operate, most notably in the ways vehicles structure the uses of downtown spaces. Yet, the transition to automated cars probably will be slow, with completion requiring 30 to 50 years. The objective of this article is to explore this transition and some useful actions downtowns might take during this crucial and lengthy period of time.

First, it’s important to be clear about the problems that many experts believe automated cars hopefully will successfully address.

Traffic Congestion Is an Old Problem That Is Now Growing Exponentially in Importance.

By 1908, the term “traffic jam” was already in popular use, so traffic congestion is a problem that has long been with us (1).

It also can be found in towns of all sizes. I remember in the late 1960s sitting in our car for over an hour in a traffic jam just outside the small town of Waynesville, OH, (population under 3,000) because the town’s streets and parking lots could not easily accommodate all the people that wanted to visit its large niche of attractive antique shops. Similarly, in the 1990s, I sat in stalled traffic for what seemed like an eternity in the small town of Manchester, VT, (population around 4,400) because so many shoppers were visiting its many outlet shops. These examples illustrate how successful small towns with strong attractions have long experienced significant traffic congestion problems.

Larger communities, especially in their downtown areas, also have long experienced traffic congestion simply because of their compactness and density – characteristics that give them a competitive advantage. However, under the new normal, their downtowns are now so successful that they are experiencing even higher levels of traffic congestion that threaten their future well-being. As a terrific report on traffic congestion in Center City Philadelphia noted:

“The revival in Center City in the last 30 years has contributed to the problem (traffic congestion), bringing a greater density of development: taller office towers, more hotels, expanding health care and educational institutions, conversion of parking lots, older industrial and office buildings to residential use and the addition of new retail, restaurant, entertainment, cultural and tourist destinations. Greater density means more people at more time times of day animating the (downtown’s) 2.2 square miles….”

“Parking and traffic regulations remain essentially unchanged in the central business district from the era when Center City was a 9-to-5 downtown with two rush-hour peaks. But today Center City is filled with office workers freed from their desks by digital technology, eating lunch and holding meetings in restaurants and cafes. It’s a destination for tourists and shoppers, animated by tens of thousands more residents, students and visitors to medical and cultural institutions. It’s become a place pulsing with vehicular and pedestrian volumes continuously throughout the day and evening hours.” (2).

The tie between a downtown’s economic success and traffic congestion also is demonstrated by this finding about traffic in Manhattan: “Since 2013, as the city’s economy and population increased, daytime speeds in the Manhattan Central Business District (from 60 Street to the Battery) declined by 11 percent” (3).

In 2017, average traffic speed in the Midtown core of that CBD was 4.7 MPH, not all that much above the 2.91 MPH average walking speed in NYC found in 2006 (4).

Traffic congestion has reached such levels in NYC that city and state leaders have tried (and failed so far) to introduce “congestion pricing” to keep vehicles from entering Manhattan. It has been implemented in London, Stockholm, and Singapore and on a few toll highways in the US such as I-66 in the Washington D.C. area and I-15 in San Diego. In other communities, altering regulations and strengthening enforcement are the major tools to cope with increased traffic congestion.

The table above shows the 25 cities with the worst traffic congestion in the USA, according to INRIX Research. They are located all over the nation. Our most populated cities certainly rank high, but it is also notable that five of these cities only had populations in the 58,000 to 212,000 range – Stamford, Tacoma, Santa Cruz, San Rafael and Santa Barbara – and that three were in the 58,000 to 91,900 range – San Rafael, Santa Cruz, and Santa Barbara.

It’s Not Just the Downtowns, It’s Also the Roads/Highways That Connect to Them. The economic health and well-being of most downtowns depend not only on the ease and costs of moving around within them, but also on how difficult and costly it is to get to and from them. The frequent traffic congestion found on the major roads leading into them can be very off-putting to those that have to work or do business in a downtown, not to mention those who want to visit for pleasure and entertainment reasons.

It’s Not Just Cars on the Roads – It’s Parking Them, Too. Many of the cars that enter a downtown stay dormant, i.e., parked, for substantial parts of the day. These parked vehicles occupy a significant proportion of a downtown’s land. As one recent report noted: “Parking consumes a significant amount of land, especially in suburban areas where auto use is highest and surface lots are more common than multi-story garages” (5). Shopping malls notoriously dedicate most of their land – about 80% — to the parking and movement of vehicles.

The extent to which downtown spaces are dedicated to auto-related uses depends a lot on how many people use cars to get to and from them. There can be considerable variation. For example, back in 2003 Michael Manville and Donald Shoup noted:

“If you took all of the parking spaces in the Los Angeles CBD and spread them horizontally in a surface lot, they would cover 81 percent of the CBD’s land area. We call this ratio—of parking area to total land area—the “parking coverage rate,” and it is higher in downtown LA than in any other downtown on earth. In San Francisco, for instance, the coverage rate is 31 percent, and in New York it is only 18 percent” (6).

Other observers have noted that: “streets and parking take up 45% of land in downtown Washington, D.C. and up to 65% in downtown Houston” (7). This variation in parking coverage rates means there will be variation in the ability of reduced parking demand to translate into freeing up land that can be put to more pedestrian friendly uses.

Downtown parking structures are also very expensive to build – about $50,000 per parking space – and add significantly to downtown development project costs, while using a lot of scarce and valuable land.

The Obvious Thing That Any Solution Must Achieve. Traffic congestion essentially means that there are too many vehicles in a defined geographic place. The obvious thing that any solution to traffic congestion must achieve is to reduce the number of vehicles in the place of interest, e.g., a downtown. Fewer vehicles means less land need for the vehicles’ movement and parking. That is precisely what many advocates (e.g., Uber, Lyft) claim that a system of automated ride-sharing vehicles can accomplish. However, as will be detailed below, there are substantial reasons to question those claims, especially for the early decades of the transition period. In turn, that can have important implications for the actions municipalities may want to take during those crucial years.

Yogi Berra: “No One Goes There Anymore – It’s Too Crowded!”

Pedestrian congestion is more of an emerging problem. Pedestrian activity can have two faces. On one hand, over the past 15 to 20 years, significant levels of pedestrian activity have become an essential element in our understanding of how successful downtowns and Main Street districts work. The well-deserved and growing attention that downtown “walkability” has garnered reflects the concerns of those active in downtown revitalization about the physical and social conditions that encourage strong pedestrian activity. It is also a de facto acknowledgment of the importance of such activity.

On the other hand, there is ample evidence that pedestrian activities can reach levels that are too dense, induce avoidance behaviors and tarnish the image of a downtown in the eyes of the public. The above statement, by the oft astute Yogi Berra, depicts a growing threat that is present daily in many of our larger downtowns and to lesser extents in some of our smaller cities. The situation here in NYC has become fairly obvious. For example, a headline in a 2016 article in the New York Times blared: “New York’s Sidewalks Are So Packed, Pedestrians Are Taking to the Streets” (8).

While this congestion may happen unsurprisingly in Manhattan on 5th Avenue in and near Rockefeller Center, in the Times Square Bowtie, along Broadway and elsewhere in Lower Manhattan, around Macy’s and near Penn Station, I have been in similar pedestrian traffic jams, though less frequently, on the sidewalks of Austin Street in Forest Hills, NY; Main Street in Flushing, NY, Jamaica Avenue in Queens, and on Fordham Road in The Bronx. Indeed, pedestrian activity has been increasing throughout the city as the table below demonstrates. NYCDOT has been counting pedestrians at 100+ locations throughout the city since 2007 annually in the spring and in the fall. It creates a Pedestrian Volume Index based on the counts at 50 of those locations. Between the Spring of 2007 and the Spring of 2016, there has been an 18.3% increase in pedestrian activity in NYC.

New York is not alone in experiencing pedestrian congestion. I have also observed it in such diverse places as Main Street in East Hampton, NY, Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Newberry Street in Boston and Ocean Drive in Miami Beach.

N.Michigan Ave in Chicago. Too many or too few pedestrians?

How many downtowns are inducing avoidance behaviors and having their images tarnished by too much pedestrian traffic congestion? My suspicion is that it is happening far more often than their leaders and stakeholders either realize or would want. Perhaps this is due to their focus on building up pedestrian activity, so the downtown can be well-activated and have ample users when that focus is no longer needed. Whatever the reason for this disregard, once again, it is the success of our revitalization efforts that creates a new challenge – too much pedestrian activity.

In turn, this situation raises the question of: at what point does the density of pedestrians begin to significantly make walking an irritating, joyless labor and an inducement for avoidance behavior? How much pedestrian traffic is too much? One suggestion is that a pedestrian needs a space envelope of about 1m2 (9). My bet is that number has no empirical data about individual behaviors, preferences and attitudes to support it! My stride alone could take up most or all of that space and I am of average height. The most important issue is how much space allows a pedestrian to feel comfortable and safe – not how many of them can be crammed onto a length of paved sidewalk.

Research also suggests that walking speeds are influenced by a community’s population size and level of economic development (10). Consequently, they may be expected to increase as a downtown revitalizes. However, increased walking speed once it crosses an unknown threshold, may deter pedestrians from strolling and window-shopping – activities critical to a downtown’s retail and entertainment operations. Moreover, as anyone visiting Times Square these days probably will attest, high volumes of pedestrian traffic can bring walking speeds down to a crawl.

High pedestrian volumes also can impede strolling and window-shopping. Retailers definitely want significant levels of pedestrian traffic, but if the volume gets too large it can become superfluous or provide too much friction for comfortable strolling and window-shopping or entering/leaving shops. This is reflected in two of my findings about the 34th Street district in Manhattan:

- The highest retail rents were not on the blockfaces with the highest pedestrian counts.

- Major retailers seem to appreciate high pedestrian counts close to Macy’s and clusters of other major retailers more than the very high pedestrian counts close to Penn Station (11).

What, then, is an optimal pedestrian flow for retailers? The Traffic Engineering Handbook 2015 (TEH) – citing data that has been in the Handbook at least since the mid-1960s – suggests that pedestrian flows larger than 1,100 to 1,600 people per hour per 22” lane are not conducive to retail activities. On a sidewalk along a downtown commercial street that has an 8’ to 12’ pedestrian zone – as recommend in Boston — that would mean between four and six 22” wide pedestrian lanes (see above table). The TEH’s recommended pedestrian volumes for retail would mean between 4,400 and 6,400 pedestrians/hr in a four-lane zone and between 6,600 and 9,600 pedestrians/hr in a six-lane zone.

However, if we look at the NYCDOT p.m. counts for the 50 locations used to construct its Pedestrian Volume Index, we find that:

- 9, or 18%, had counts above 4,400/hr

- Only 5, or 10%, had counts above 6,400/hr

- Only 2, or 4%, had counts above 9,600/hr. (One location is by Macy’s, the other is across from Penn Station.)

The 1,600 people/hr/lane rate seems to result in a very high pedestrian flow even by NYC standards, one that makes me doubt it is conducive to strolling and window- shopping. The 1,100 people/hr/la rate is still relatively high, but probably closer to what is conducive to having successful retailing. More research on this question is needed.

Under the new normal, as more and more downtowns succeed, as more of them have significant levels of pedestrian traffic, more of them probably will have pedestrian congestion problems.

The Auto-Pedestrian Congestion Interaction. Of course, there also are basic relationships between pedestrian and auto congestion. They each can reinforce the other. For instance, dense auto traffic makes it harder for pedestrians to cross streets, while dense pedestrian flows at corners makes it more difficult for autos to make turns. To help cope with this situation in NYC “a new tool has emerged to help increase pedestrian safety: The Pedestrian/Traffic Manager—an individual trained and certified exclusively in the movement and safety of pedestrians in high density areas (12).

Spaces for vehicles turned into spaces for people. Broadway near 36th Street in Manhattan

Historically, auto traffic and pedestrian congestion also have fought each other. For example, early in the transition to automobiles, wide city sidewalks were reduced in size to provide more room for vehicle traffic. Of late, cities such as NYC, have been doing the opposite, emptying road bed spaces of vehicles to provide more room for pedestrians – see the above photo. Many urbanists believe that autonomous vehicles will enable much more of the street spaces used by vehicles to be converted into vibrant public spaces for pedestrians.

The Promises of the Automated Car Revolution

These are the major positive impacts that the changeover to automated vehicles promises to achieve:

- Much safer vehicles due to automation/computerization of driving functions and new safety features.

- Reduced CO2 emissions created by the switch to automated vehicles powered by electric engines.

- Reduced need for parking spaces created by:

- Reduced private ownership of vehicles means less need for residential parking.

- Increased use of ride for hire automated vehicles for work and pleasure trips means reduced need of parking spaces for visitors to office buildings, manufacturing plants, shopping malls, sports stadiums and arenas, government offices, etc.

- Reduced need for land used for highways, roads, and streets because:

- There will be significantly fewer vehicles because there will be vastly increased ride-sharing.

- More, importantly, there will be fewer vehicle miles driven since there will be vastly increased ride-sharing.

- Vehicles will need narrower road spaces because vehicles will be more accurately guided by GPS or road beacon systems.

In 2017, these promises stimulated the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) to issue its future-peering and optimistic Blueprint for Autonomous Urbanism (13). In this vision of our urban future, the adverse impacts of automobiles are substantially diminished, and the needs, comforts, and pleasures of people are the engines for urban design. For example, under the Blueprint, people would have more spaces for walking and leisure and vehicle speeds would be so slowed pedestrians could even cross streets midblock! There is much to admire in this vision, but there also are many questions about when and how it might be realized.

Some of the claimed benefits of the automated car revolution, especially when made by people with strong vested interests in it, strain credulity and seem more like marketing puff. Often this puffery also is full of politically tenuous positions. The leaders of Lyft are good examples. As reported in a 2018 article on Verge:

“Lyft’s… co-founders, John Zimmer and Logan Green, have released policy papers predicting the end of personal car ownership in major cities by 2025, and calling for more people to carpool by charging a fee to those who don’t” (14).

With about 263 million passenger cars, motorcycles, lorries, buses and other vehicles now registered in the US, it is certainly dubious that personal car ownership will end in our major cities by 2027. Also, only political naïfs would believe that fining people who do not carpool would not create huge political problems.

More generally, Lyft stresses that ride-hailing could reduce the number of personally owned cars on the roads (15). According to its spokesman: ”Lyft is focused on making personal car ownership optional by getting more people to share a ride, helping to reduce car ownership, and partnering with public transportation”(16). Uber, according to its spokesman has a similar goal: “Uber’s long-term goal is to end the reliance on personal vehicles and allow a mix of public transportation and services like Uber” (17).

Of course, there is another possibility: ride-hailing services will increase the number of vehicles on the road and significantly worsen urban traffic congestion.

The Predictions

The Importance of the Long Transition Period. There is a real need for downtown and municipal leaders to recognize that the transition to autonomous vehicles will take decades to complete (18). Until then, there will be very long periods when roadways will be shared by autonomous vehicles, those that are legacies, and those that are driven, but have lots of hi-tech safety features to protect their drivers and passengers. Even the transition away from gasoline powered vehicles will likely take decades to complete. One of the most important issues for downtown and municipal leaders is when, if ever, will the number of automated vehicles reach the point where they will reduce the need for parking spaces, roads and highways?

Autonomous vehicles will have a relatively small presence in the near future. In its 2016 report, McKinsey concluded that worldwide: “Once technological and regulatory issues have been resolved, up to 15 percent of new sold cars sold in 2030 could be fully autonomous” (19). McKinsey also concluded that by 2050, about 33% of new cars sold worldwide could potentially be a shared vehicle (20). That suggests that the vast majority of vehicles sold 30 years from now will still be of the unshared variety!

IHS Markit looked at autonomous vehicle sales in the 2020 to 2040 period in the Americas (see above chart). It predicted that autonomous vehicle sales in the U.S. would reach 7.9 million units/yr by 2040 (21). Given that annual vehicle sales in the US in recent years have been in the 15 million to 17 million range, it appears probable that most vehicles sold in the US for the coming 20+ years will be legacy type vehicles, though many of their operations and safety features may become automated.

Municipalities and downtowns that forget to take into account the very large number of legacy and unshared vehicles do so at their own economic peril! Yet, the growth of autonomous and shared vehicles will mean that they, too, cannot be ignored.

BP, the big oil company, in its Energy Outlook 2018, sees only 25% of the car sales worldwide in 2040 being electric powered. Even if we allow a 100% or even a 200% error factor to offset any possible BP bias, that still leaves a whole lot of non-electric vehicles being sold – and many more will still be on the road. These data suggest that the ability of autonomous electric-engined cars to reduce CO2 emissions probably will take many decades to reach significant levels!

The BP data are also interesting because they show that the number of passenger vehicle kilometers (vkm) powered by electricity will grow significantly faster than the sales of electric powered vehicles in 2040. This also points out that the numbers of miles/kilometers traveled by vehicles, with and without passengers, probably are far more important variables for analyzing traffic congestion than auto ownership statistics.

The following quote from the Driverless Future report is extremely important. It notes that:” The possibility that millions of car owners could shift to ridesourcing and give up car ownership offers an opportunity to alleviate congestion, provide equitable access to jobs and services, and create development that is more inclusive and sustainable. However, it is also expected that vehicle miles traveled will rise as consumers are exposed to new mobility services. This would lead to more congestion” (22). This illustrates the importance of the vehicle miles traveled variable and its associated data.

The Speed of The Transition Will Probably Vary by the Type of City or Town. The McKinsey study also concluded that: “City type will replace country or region as the most relevant segmentation dimension that determines mobility behavior and, thus, the speed and scope of the automotive revolution” (23). In McKinsey’s view, in the US, regions automated vehicles will have marginal penetration in small towns and rural areas, where private cars will continue to be the preferred means of transportation. However, in the larger, most congested cities car ownership and use is more burdensome and shared mobility has significant competitive advantages and consequent higher probabilities of adoption (24).

Another relevant study, “Driverless Future: A Policy Roadmap for City Leaders”, by Arcadis, HR&A, and Sam Schwartz, argues that the shift from car ownership to using shared automated vehicles will vary according to the strengths of the following variables:

- Population density.

- Level of car ownership.

- Strength of public transit.

- Residential density (units/acre).

The above table is constructed from data on page 9 of the Driverless Future report. The analysis of shifts from personal car use for commuting to the use of shared automated vehicles is cost driven. This analysis then ties the shifts with residential unit density. Areas with 0-3 units per acre are deemed now likely to prefer autos for commuting; places with 10-20 units prefer bus transit and places with 30-150+ units per acre prefer rail. The analysis projects that car ownership will probably shift into the use of shared automated vehicles (AVs) to a much greater extent in the NY-NJ MSA, 46% to 60%, than in either the L.A. MSA, 36% to 46% or the Dallas-Ft Worth MSA, 21% to 31%.

The conclusions that the shift from the use of personal cars to shared automated vehicles will be greater in the NYC Metro than in the L.A. and Dallas-Ft Worth Metros, and that it will be lowest in the Dallas-Ft Worth Metro appear to me to be correct. The overall differences on the estimates for the NY and Dallas Metros are 25% for the low estimates and 36.4% for the high estimates. However, to me, there appears to be a number of questionable things about this analysis. For example, the ranges between the lowest and highest estimates of the reductions in personal vehicle ownership in all instances are quite high. That strongly suggests these should be treated as ballpark estimates – valuable if used carefully, but far from definitive. In all fairness, the study’s authors do state conditionally that the MSA in question “could experience a shift of….”

Also, the residential density variable really does not seem to make all that much difference:

- For the NY Metro the range for the low estimate across the five residential unit density categories is 37% to 45.7%, a delta of 8.7%. The range for the high estimate is 66.7% to 70.0%, a delta of 3.3%

- For the L.A. Metro the range for the low estimate across the five categories is 35.5% to 38.6%, a delta of 3.1%. The range for the high estimate is 44.2% to 46.8%, a delta of 2.1%

- For the Dallas -Ft Worth Metro the range for the low estimate across the five categories is 18.3% to 20%, a delta of 1.7%. The range for the high estimate is 25.0% to 33.6%, a delta of 8.6%.

The focus on car ownership is questionable. As the BP and Driverless Future reports discussed above indicate, vehicle miles traveled is probably the really crucial variable. Certainly, it is more probative when analyzing the issues of CO2 emissions, road safety, traffic congestion, and the land needed for roads and highways. However, data on the use of personal cars to commute to work may be far easier and cheaper to obtain.

Most importantly, the assumption that the shift away from personal car use will be based solely on economic factors should be strongly questioned. The reasons why only 25% of NYC’s residents use their personal cars to get to work and 52.9% use public transit, while 75.6% of Dallas’s residents drive their cars to work and only 9.5% use public transit are probably far more historical and cultural than economic. These cultural factors are also present in L.A., as well as in such cities as Charlotte, NC, and Columbus, OH. They are why these communities do not have stronger and better utilized public transit systems – it isn’t that these cities lacked the wealth or economic strength.

In such communities, it will not be easy for even cheaply priced rides in shared automated vehicle to overcome the feelings of power, control, freedom, comfort, and even joy, that riding in their own vehicles provides to a whole lot of Americans. For these car owners, the benefits may be worth spending a good deal of money to retain them. Just consider that the average cost of an off-street parking space in NYC is about $400/mo and in Manhattan, as shown in the illustration below, the prices can be a whole lot higher, $600 to $1,000. These car owners have a proven ability to accept an awful lot of financial pain in order to drive to work. Forecasts of their abandoning their own vehicles for cheaper shared rides to my mind lacks similar levels of evidentiary support!

Of course, the implementation of a steep congestion pricing program could make the economic factors much more salient. But, but, but….

Already, in many of our largest cities, less than half of their residents commute to work alone in their private cars: 22% in NYC; 35% in San Francisco, 38.9% in Boston; 49.2% in Seattle and 49.5% in Chicago. The introduction of shared autonomous vehicles into their congested areas seems unlikely to capture customers from those driving their cars. More likely are those already using other transportation modes. Because of that their introduction might actually increase congestion. Some evidence for this contention is provided by a very solid study of the impacts of “TNCs”, a.k.a. Uber and Lyft, on congestion in NYC by Schaller Consulting. While the vast majority of the TNCs’ trips are neither shared nor automated, Schaller’s major findings are still salient because they strongly indicate the types of riders who are prone to be attracted by automated ridesharing services:

- “TNCs accounted for the addition of 600 million miles of vehicular travel to the city’s roadway network over the past three years, after accounting for declines in yellow cab mileage and mileage in personal vehicles. The additional 600 million miles exceeds the total mileage driven by yellow cabs in Manhattan.”

- “Growth in trips, passengers and mileage is seen throughout the city as TNCs attracted yellow cab riders, those who would otherwise use the bus, subway or their personal vehicle, and people who would not otherwise have made the trip.”

- “TNC mileage nonetheless continues to grow rapidly because exclusive-ride trips still predominate, and because most TNC customers are coming from transit, walking and biking. Migration from public transit translates to increased mileage even if the trips are shared.”

- “Trip growth in Manhattan has been concentrated during the morning and evening peak periods, when yellow cab shift changes produced a shortage of cab availability, and late evenings and weekends when passengers may prefer the comfort and convenience of TNCs over yellow cabs or transit services”.

- “A continuation of TNC-led growth in travel is not a sustainable way to grow the city” (25).

Models, such as the one employed by Driverless Future, predict that the highest conversion from commuting by car to the use of shared automated vehicles will be in many dense urban residential areas where that often will mean relatively few people actually make the change because so few are now using their cars On the other hand, the introduction of many shared automated vehicles into such urban environments may worsen traffic congestion. It may well be, that congestion in Manhattan will only be reduced if shared automated vehicles are only used to transport out-of-town commuters.

Finally, the modeling of, and discussions about automated vehicles have almost exclusively focused on those carrying passengers, but auto makers, such as Ford and even Tesla, see huge market opportunities for those that will deliver freight to companies and purchases to consumers. A major feature of the current retail revolution is the quest to provide at least same day, if not same hour delivery of online purchases. The numbers of these vehicles could rival those used for conveying passengers.

One solution may be limiting freight deliveries to slow, after dark hours, though some businesses definitely will strongly resist. The real challenge is the final 100 yards problem of getting the package from the automated delivery vehicle into the hands of the customer, where after dark deliveries probably will pose a problem. Amazon currently is experimenting with using drones for package deliveries, which may pose still other problems. One way or another automated package delivery may pose major problems for downtowns and cities sooner than the automated passenger vehicles because it may be relatively easy for companies like Amazon, Walmart, Kroger, Best Buy, Macy’s or even Uber and Lyft to field fleets of them to meet already proven demand. Downtown and municipal leaders need to keep the regulation of automated freight and package deliveries high on their agendas – and finding the right ones probably will not be easy.

The Sine Qua Non for Solving the Traffic Congestion Problem

It’s been said that our dense urban areas, such as downtowns, have a geometry problem: there is a finite amount of land and a growing number of automobiles that want to use it. Passenger vehicles can vary both in how many passengers they have the capacity to transport and how many they actually do carry. The photo montage below assembled by Jon Orcutt demonstrates that if each only carries one passenger, then the same number of vehicles, occupying the same amount of road space, regardless of whether they are private cars, Uber vehicles or autonomous cars. If all the seats in these vehicles were occupied, then about four times as many people could be transported without increasing the number of vehicles or the amounts of needed road and parking spaces to accommodate them. Those are the basic advantages for the community of ride-sharing/carpooling efforts.

Recent simulations, however, have indicated that for ride-sharing to have meaningful positive impacts, they will have to carry more than the four or five passengers that is the capacity of our average passenger cars. The ride-sharing vehicles will need to carry between 12 to 18 passengers. As one very astute observer has noted: “… governments will need to support the growth and development of fleets of 12- or 18-seat minibuses, to supplement (rather than replace) public transit systems, which they will also need to support” (26).

Riding in shared minibuses may not have as much allure for the riding public as the image of riding alone in a well-appointed automated vehicle. One may also wonder what the images of Uber and Lyft may be once they become fleets of minibuses or what the value of their shares of stock will be.

One also might wonder about the appeal of riding in close quarters with a group of strangers. To many, it may sound like being in the rush-hour in the NYC subway. A 2018 study in Greenwich, England found that survey respondents associated a good deal of potential social discomfort with ridesharing. They felt that a “key emotional benefit to travelling by car or taxi is the sense of control and personal space.” While public transport does not have such spaces, it does have informal ‘social rules’ that are applied. Respondents were “unsure on how such ‘unwritten rules’ would apply to ride-sharing.” (27).

Uber and Lyft are the current major pretenders to the shared automated vehicle service throne, though they are basically still app-initiated ride- hailing operations. So far, the public’s disposition to using them is not favorable. A 2016 survey for Vox found that 53% of its respondents said it was unlikely they would ride in an Uber or Lyft vehicle in the next ten years and 61% reported they were unlikely to use an Uber-style self-driving car service if it becomes available in their area. That is a lot of people who do not want to use the largest wannabe automated rideshare services (28).

A rigorous study by researchers at UC-Davis of their current actual users in seven major metro areas — 4,000 users in the metro areas of Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. — produced many interesting findings:

- “In major cities, 21% of adults personally use ride-hailing services; an additional 9% use ride- hailing with friends….”

- “Parking represents the top reason that urban ride-hailing users substitute a ride-hailing service in place of driving themselves (37%).

- “Avoiding driving when drinking is another top reason that those who own vehicles opt to use ride-hailing versus drive themselves (33%).”

- “The majority of ride-hailing users (91%) have not made any changes with regards to whether or not they own a vehicle.”

- “Directionally, based on mode substitution and ride-hailing frequency of use data, we conclude that ride-hailing is currently likely to contribute to growth in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in the major cities represented in this study” (29). In other words, the ride-hailing services right now appear likely to make traffic in our cities more congested.

If people are afraid to ride in self-driving vehicles, then they surely will not be ride-sharing in them. A survey done for the AAA in 2017 found that: ‘Three-quarters of U.S. drivers would be afraid to ride in a self-driving vehicle, while 19 percent would trust the vehicle and 4 percent are unsure’. Baby Boomers were more afraid (85 per cent) than Millennials (73 per cent), but the latter’s percentage is still very high (30). A year later AAA’s annual survey found that fear levels had dropped to 63 percent (31). However, that survey was completed before the well-publicized death caused by an Uber automated vehicle in AZ.

If ridesharing is indeed the key to reducing traffic congestion, then the strategic imperative for downtown and municipal leaders concerned about this problem must be to devise and implement policies and programs that will sufficiently incentivize the public’s use of fleets of 12- or 18-seat minibuses. Simply getting them out on the road will not be enough. They probably will need to be very appealing in terms of safety, convenience, comfort, and enjoyment as well as price.

The Probable Persistence of the Multi-Modal Regional Traveler

The essence of suburban communities is that their residents are relatively dispersed and, perhaps outside of their downtown or Main Street areas, walking to destinations is rather difficult, while they lack public transportation, so residents are very car-dependent. To a lesser, but still significant extent, the same can be said of some the suburban-like neighborhoods found in some of our larger cities. In fact, many of them actually started out as suburbs.

A study of Lyft and Uber in Austin TX found that when these two ride-hailing services were briefly kicked out of town, their riders returned to using their own cars. According to Robert Hampshire, lead author of the study: “The takeaway isn’t so much that Uber and Lyft reduce the need to own a car, but rather they limit how often people use a car they already own…. A large fraction of these people already had a car and just weren’t using it as much” (32).

These Uber/Lyft riders and car owners in Austin are “multi-modal” travelers within their region. My impression is that too many of the studies about autonomous car impacts neglect looking at the significant numbers of residents in neighborhoods and towns in metropolitan areas who have long been “multi-modal” travelers. I previously have written about the situation here in the outer boroughs of NYC:

“44 percent of the households in both the Bronx and Brooklyn have cars, while 64 percent do in Queens. Even in Manhattan, where garage spaces can cost ($1,000+ per month) and in several of its zip codes over 40 percent of the residents walk to work, 23 percent of the households own cars. The car-owning residents in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens tend to be tri-modal from a transportation perspective. They walk a lot to local destinations — perhaps longer and more frequently than anywhere else in the US — and use subways, buses, and even commuter rail to get to work. But they are extremely likely to use their cars to travel to any other types of destinations “ (33).

Residents in many of the suburbs in the NY-NJ- NYC- Newark MSA also are multi-modal travelers. Take Maplewood, NJ, for example, a town with roughly 24,4000 residents, among whom about 57% are in core creative class occupations. The town has a direct commuter rail connection to Manhattan and Newark. Among its residents who are in the labor force about 56% commute to work alone in their personal cars, but:

- 30.9% commute to work via public transit (mostly by rail).

- 8.0% worked at home.

- 1.2% walked to work.

I would bet the family farm – if we had one – that almost all of these employed Maplewood residents who do not use a vehicle to commute to work also are in households that have one or more automobiles. If they didn’t, they would find it very difficult to get around town, much less do comparison shopping or visit major entertainment venues in other communities (see table below).

While commutation trips may offer the best opportunities for people to give up the use of one of their cars, strong arguments can be made that:

- The degree to which that might occur will vary and certainly be less than 100% (see the discussion of the Driverless Future study above).

- Residents in the suburbs and in neighborhoods outside of large city cores make many trips to non-work-related destinations. The use of vehicles shared with other people going to these non-work-related destinations may often not be comfortable or desirable while being the sole occupant of automated vehicle operated by a ride-hailing service might not be very affordable. Personal cars will remain for them the best transportation mode, even among those who stopped using them to commute to work.

Can you really imagine taking a shared vehicle with 10 to 18 passengers to transport you and your shopping bags home after a weekly shopping trip to a large supermarket or a shopping trip to COSTCO? And what about traveling home after shopping trips to a large mall or big box store? Think also about going to a play or concert at a venue that is within a 30-minute drive in a shared automated vehicle that has numerous stops to pick up and discharge passengers? That scenario brings to mind the “airport shuttles” I’ve used to get to my hotels on a few business trips. They were cheaper than taxis, but much more time-consuming and aggravating because of their extra stops. They also were not all that comfortable, but then that holds for taxis, too.

Now some would say that the shopping bags could be delivered by another automated vehicle. Indeed, one of the quickest and largest adoptions of automated vehicles probably will be the fleets of them used to deliver packages. Their numbers initially may well grow faster than their use by passengers because many fewer decision-makers will be involved and they will have a clarity of purpose and benefits. Nevertheless, using AVs as an adjunct to shopping trips to brick and mortar stores to transport the purchases would mean two vehicles would be used on a person’s shopping trip instead of just one.

I live in Kew Gardens, NY, a community that the USPS, in its usual wisdom, divided across two zip code areas. The 11415 area contains only Kew Gardens residents, while the 11418 area has mostly non-Kew Gardens residents. The density of residential units in 11415 is 25.2 units/acre, in 11418 it’s 11.4 units/acre. In contrast, the posher and much more affluent 10021 zip code in Manhattan has a residential unit density of 114.7/acre. Kew Gardens was built as a suburb of Manhattan and even with its many apartment buildings it still retains many large single-family homes and many suburban characteristics. Those who know NYC well, know that many neighborhoods in the outer boroughs share these suburban characteristics. One of them being that many residents are multi-modal travelers within the region.

The above table lists three of destinations we go to with some regularity by car because reaching them via public transportation simply takes too long and involves transfers that are too often “iffy.” I used my Uber app on a Thursday mid-morning, to see what it would cost for them to then take us to these destinations. Uber’s shared ride services were not available for me, so I selected the Economy option. The prices for these trips, presented in the above table, are plainly unreasonable. $133.40 (plus tip?) to get and from Jones Beach?

I’ve read that prices for Uber rides can be expected to go down, especially in shared automated vehicles that probably have 8+ passengers. Do I really want to go on this automated mini-bus with my cooler, beach chairs, and umbrella? Or would I rather have my own vehicle? Moreover, how much cheaper would the ride be? Even 50% less would not be enticing. Furthermore, without a driver, how would sanitation and order be maintained within a shared vehicle?

Here in Kew Gardens and neighboring Forest Hills we can reach Manhattan via the Long Island Rail Road and several subway lines. Unless traffic congestion is severely reduced and automated shared vehicle ride costs are very affordable, I doubt that many residents will use the shared automated vehicles to commute to Manhattan. However, many residents live more than a half-mile from the subway and LIRR stations and use a bus or car service to get to and from them. Uber-type services may be able to capture some of these commuters. However, the fact that the city now charges just one fare to riders who use the bus and transfer to the subway probably severely limits that penetration. Before that program was instituted, fleets of private vans – shared but not automated vehicles — brought subway riders from southeastern and western Queens to Jamaica Center’s subway stations. The one-fare program significantly reduced van ridership. The poor frequency of many bus lines in outer borough neighborhoods, on the other hand, makes Uber and Lyft attractive. Interesting that the UC-Davis seven-city study discussed above found that the Uber-Lyft operations were complementary to rail transit, but hurt buses and taxis.

Back in the 1950s, our apartment complex had a car service that would take tenants to and from the subway. I can envision several condo buildings in our community that might in the future have their own automated “station car,” probably bought second hand, to perform this chore – if the city would give its permission.

Maplewood and many other towns and cities in the NYC Metro Area are in situations very similar to those described in Kew Gardens (see table above). They have commuter rail stations with parking lots filled to the gills with the cars of commuting train riders. Ridesharing automated vehicles may be a way to deflate the demand for these scarce station parking spaces and perhaps put the land to better uses. Summit, NJ, is already experimenting with using Uber to forestall the need to build additional parking capacity. Municipal leaders in such communities should definitely be exploring this possible use of shared automated vehicles to reduce station area parking.

In Chester, NJ, (population about 1,500) Alstede Farms runs a free shuttle between it and the NJT station in Gladstone, NJ, as well as to the Historic Main Street Chester area during the summer months. In the Denver Metro Area, the City of Englewood (population about 34,000) has a free trolley that transports riders to 19 stops connecting CityCenter Englewood, businesses in downtown Englewood, and the medical facilities in and near Craig Hospital and Swedish Medical Center. Note that the Englewood shuttle does not impact on how their riders come to Englewood, but helped them move around the tows more easily while there. Many other suburban towns may want to explore the potentials of similarly using shared automated vehicles as shuttles between major commercial nodes, though there are sure to be financial challenges and require strong corporate sponsorship.

Whether or not the shared automated vehicles can be used similarly as shuttles to make it easier for suburban residents and visitors to get to and from their downtowns is another issue.

Municipal leaders responsible for such suburban communities and suburban-like neighborhoods in our larger cities must realize that these places are not like Manhattan, Center City Philadelphia, downtown Chicago or downtown Boston where a lot of non-commuting destinations are within easy walking distances and car ownership is relatively low. Too many of their residents’ non-commuting trips are unlikely to be adequately served by shared automated vehicles for probably decades to come – if ever – and they will probably need to have a personal vehicle at their disposal. This strongly suggests that, for the foreseeable future, multi-unit residential buildings probably still will need parking capacity of about one space per unit.

As noted above, parking consumes a lot of land in suburban communities, especially when they have large workforces arriving weekdays and/or large shopping malls within their borders. The ability of shared automated vehicles to reduce the amount of suburban land used for parking is not clear. Yes, they probably can reduce the amount of land needed for rail station parking. While a lot of shopping mall land is changing use simply because some malls are closing, it is doubtful that high percentages of shoppers will rideshare to retail stores.

A number of suburban downtowns, e.g., Englewood, NJ, and Great Neck Plaza, NY, have found that parking structures are badly underutilized even before any significant appearance of Uber, Lyft or shared autonomous vehicles. Their potential patrons strongly prefer surface lots, and/or they deem the location of the garages to be too peripheral. Futureproofing these garages –- i.e., making it feasible to convert all or parts of them to other, non-auto related uses -– probably would have been a good idea, but not because of the impacts of shared automated vehicles.

if the suburban roads are not badly congested and the job site has ample parking, why would workers switch to shared automated vehicles on their commutes? The price differential with using personal cars would have to be awesome. Of course, a good number of suburban roads are badly congested – e.g., Rte 1 in NJ between Trenton and New Brunswick and Rte 9 through Boston’s western suburbs. However, overcoming the dispersion of rider residences may be a significant limiting factor. To get into your own car to travel to and park at a rideshare pick-up point may not seem either appealing or logical to many potential suburban users. The alternative of having the vehicle makes numerous pickups also does not seem likely to be attractive to riders. Ridesharing programs have been around for decades and the reasons they did not become far more popular probably still have significant applicability today when envisioning automated ridesharing systems.

But, We’re Driving Fewer Miles and Millennials Don’t Like Cars

One of the arguments frequently offered to support the contention that Americans will easily adapt to automated vehicles is that they are driving fewer miles. Although this was true during and briefly after the Great Recession, in recent years Americans are driving more than ever before – see the above chart on vehicle miles traveled (VMT). In 2016 Americans drove a record number of 3.22 trillion miles on the nation’s roads…, up 2.8 percent from 3.1 trillion miles in 2015” (34). It was the fifth straight year of increased vehicle miles driven.

Moreover, projections by the Federal Highway Administration suggest total VMT by all vehicle types will grow on average 1.07% annually through 2035. However, the growth will slow significantly between 2035-2045 to bring annual growth rate for the entire 30-year 2015-2045 forecast period to 0.78%. This would be quite a moderation in the annual VMT growth rate from the past 30 years when it grew at an average rate of 2% — but it still would be growth (35).

Closer to 2010, Millennials were seen as an urban loving, car and driving hating, experience wanting, under-employed, relatively poor and burdened with large student debts, non-nesting, non-home buying age cohort. Surveys also showed them to be the most likely to use app-summoned ride-hailing services such as Uber and the most willing to ride in driverless cars.

Today, our understanding of the Millennials is changing as their life situations have significantly altered. They are now the largest age cohort. With time and age, they have become better employed, are earning more money, and have started to nest. That means they are marrying, having children and buying homes and cars. The Millennials were deeply impacted by the Great Recession with it forcing them to defer nesting and buying homes and cars for many years.

Moreover, as a Zillow survey found: “Almost 50 percent of millennial homeowners live in the suburbs, while 33 percent live in an urban neighborhood and just 20 percent live in a rural area” (36). That means that about 70% of them will live in relatively low-density population areas where cars are an essential means of getting around for even everyday chores. Even back in 2014, a survey found that 80% of Millennials surveyed said that they plan to purchase a vehicle in the next five years (37). According to a report in Forbes, Millennials are buying cars in significant numbers: “…(M)illennials, now the largest generation in the U.S., bought 4 million cars and trucks last year, second only to the baby boomers, according to J.D. Power’s Power Information Network” (38)

The rural Millennials are unlikely to have a strong propensity to use shared automated vehicles. The propensity of newly nested suburban Millennials to use such vehicles is unknown at this point in time. The key question is if their assumption of a more traditional lifestyle correlates with more conventional needs and attitudes relating to transportation modes. On one hand, my observations of Millennials now living in the suburbs suggests that they are strong advocates for well-activated downtowns and that suggests that they may make their own imprints on their suburban communities. Yet, they cannot avoid being effected by the significant dispersion most suburbs have,

Looking to the Future States of Traffic and Pedestrian Congestion

Shared automated vehicles provide no silver bullet solutions to these problems and if not properly implemented that can actually increase their severity.

The need to have a successful ridesharing system composed of minibuses capable of carrying 12 to 18 passengers means attracting sufficient users probably will be a huge challenge.

Too little attention is being paid now to the probable problems that will emerge during the long transition period when legacy, driven and automated passenger and freight/package carrying vehicles will share our roads.

A real challenge is that for the traffic congestion in our center cities to be reduced it is primarily the car use of their non-resident regular users that must be changed. That means huge jurisdictional and political problems.

There are real dangers that civic leaders will buy into the shared autonomous car dream too early and make premature moves on reducing parking space requirements or attempting major street and road redesigns. Small scale projects, such as using shared automated vehicles to take suburban commuters to their rail stations, will probably be most appropriate for several decades. Huge freeing of parking and road spaces for repurposing and improving a downtown’s walkability and public spaces are also unlikely for several decades, if ever.

Concern about the safety of a vehicle’s passengers, passengers in other vehicles and pedestrians should be a primary focus now and until automated systems are proven not just in test/experimental situations, but by years of actual full implementation. The Uber traffic accident in AZ showed a shameful lack of public sector concern. The appropriate regulation of the industry will be difficult to design and implement. The baby needs real care, though we don’t want to drown it in its bathwater.

ENDNOTES

1) See: https://www.etymonline.com/word/traffic

2) “CENTER CITY REPORTS: KEEP PHILADELPHIA MOVING” produced by the Center City District, the Central Philadelphia Development Corporation and the Central Philadelphia Transportation Management Association, pp1-2. https://centercityphila.org/research-reports/2018congestion

3) “Mayor’s Management Report,” City of New York, September 2016. Figures are for fiscal year 2013 and 2016. Cited in Bruce Shaller. ”UNSUSTAINABLE? The Growth of App-Based Ride Services and Traffic, Travel and the Future of New York City,” p.18.) http://www.schallerconsult.com/rideservices/unsustainable.pdf

4) For auto speed see: Fix NYC Advisory Panel Report, January 2018, p.7. http://hntb.com/HNTB/media/HNTBMediaLibrary/Home/Fix-NYC-Panel-Report.pdf . For NYC pedestrian speed see: Rachel Pincus. “Yes, Your Sidewalk Etiquette Could Be Better.” CITYLAB Aug 28, 2015. https://www.citylab.com/life/2015/08/how-to-share-the-sidewalk/401660/

5) DRIVERLESS FUTURE: A POLICY ROADMAP FOR CITY LEADERS, by Arcadis, HR&A, and Sam Schwartz http://driverlessfuture.webflow.io/

6) Michael Manville and Donald Shoup, People, Parking, and Cities, Access, Number 25, Fall 2004, p 7 http://shoup.bol.ucla.edu/People,Parking,Cities.pdf

7) See endnote 5, p.12.

8) Winnie Hu, “New York’s Sidewalks Are So Packed, Pedestrians Are Taking to the Streets.” The New York Times. June 30, 2016. http://nyti.ms/29dy7m3

9) See endnote 2, p.4.

10) Eric Jaffe. “Why People in Cities Walk Fast.” CITYLAB, Mar 21, 2012 https://www.citylab.com/life/2012/03/why-people-cities-walk-fast/1550/

11) N. David Milder. ”34TH Street: A Fabled Shopping District and Window on the Future of Downtown Retailing.” Downtown Curmudgeon. April 15, 2017. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2017/04/34th-street-a-fabled-shopping-district-and-window-on-the-future-of-downtown-retailing

12) Ileanna Pappas and Janet Campbell. “A New Breed of Pedestrian Advocate is Making City Streets Safer for Everyone.” Planetizen, Sept. 13, 2013. https://www.planetizen.com/node/65198

13) It can be downloaded at: https://nacto.org/publication/bau/blueprint-for-autonomous-urbanism/

14) Andrew J. Hawkins “Lyft thinks we can end traffic congestion and save $1 trillion by selling our second cars: Do we really need that second car?’ The Verge, Jan 10, 2018. https://www.theverge.com/2018/1/10/16870732/lyft-traffic-congestion-car-ownership-ces-2018

15) AP. “Studies are increasingly clear: Uber, Lyft congest cities.” https://www.apnews.com/e47ebfaa1b184130984e2f3501bd125d

16) Ibid.

17) Ibid.

18) N. David Milder. “Let’s Get Real About: Self-Driving Cars. Social and Political Engineering Will Also Be Required.” Downtown Curmudgeon Blog. Sept 7, 2017. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2017/09/lets-get-real-about-the-supposedly-imminent-nirvana-of-self-driving-cars

19) McKinsey Auto 2030 Report Jan 2016, p 11. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/disruptive-trends-that-will-transform-the-auto-industry

20) Ibid, p.9.

21) Kate Gibson. “Forecast: Autonomous-Vehicle Sales to Top 33 Million in 2040. The Drive. 2/21/18. http://www.thedrive.com/sheetmetal/17298/forecast-autonomous-vehicle-sales-to-top-33-million-in-2040

22) See endnote 5. The italicized emphasis was added by NDM.

23) Endnote 19, p. 9

24) Ibid.

25) Schaller Consulting. UNSUSTAINABLE? The Growth of App-Based Ride Services and Traffic, Travel and the Future of New York City. February 27, 2017. P.1.

26) David Roberts. Unless we share them, self-driving vehicles will just make traffic worse – Vox, 7/24/17, p.9 https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/5/18/15604744/self-driving-cars-cities

27) MERGE Greenwich: Customer attitudes to Autonomous Vehicles and Ride-sharing. April 2018. https://mergegreenwich.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2018/04/MERGE-Greenwich-Consumer-attitudes-to-AV-ride-sharing-3.pdf

28) Timothy B. Lee. “We polled Americans about self-driving cars. Here’s what they told us. Vox. Aug 29, 2016. https://www.vox.com/2016/8/29/12647854/uber-self-driving-poll

29) Regina R. Clewlow Gouri and Shankar Mishra. “Disruptive Transportation: The Adoption, Utilization, and Impacts of Ride-Hailing in the United States.” Research Report – UCD-ITS-RR-17-07. October 2017. Institute of Transportation Studies ? University of California, Davis. Pp. 1,2.

30) Erin Stepp. ‘Americans Feel Unsafe Sharing the Road with Fully Self-Driving Cars: AAA Fact Sheet: Vehicle technology Survey — Phase II. 2017’, Newsroom/AAA.com, available at http://newsroom.aaa.com/2017/03/americans- feel-unsafe-sharing-road-fully-self-driving-cars/

31) Erin Stepp. ‘More Americans Willing to Ride in Fully SelfDriving Cars” January 24, 2018. Newsroom/AAA.com. https://newsroom.aaa.com/2018/01/americans-willing-ride-fully-self-driving-cars/

32) Danielle Muoio. “Uber and Lyft could destroy car ownership in major cities.” Business Insider. Sept 4, 2017. http://www.businessinsider.com/uber-and-lyft-limit-personal-car-use-study-2017-8

33) N. David Milder. “Let’s get real about self-driving cars: The transition will take a

significant amount of time.” Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, February 15 2018. Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 223–232, p. 228

34) David Schaper , “Record Number Of Miles Driven In U.S. Last Year.” NPR. February 21, 2017 https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/02/21/516512439/record-number-of-miles-driven-in-u-s-last-year

35) Office of Highway Policy Information. Federal Highway Administration. “FHWA Forecasts of Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT): Spring 2017.” May 4, 2017. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/tables/vmt/vmt_forecast_sum.pdf

36) See: http://zillow.mediaroom.com/2017-03-01-Millennials-Buying-in-the-Suburbs

37) Deloitte. 2014 Global Automotive Consumer Study 6. http://tinyurl.com/y9ygdeew

38) Joann Muller. Mar 24, 2016 “Millennials Finally Show Up At Car Dealerships (And Automakers Breathe Easier).” FORBES. http://tinyurl.com/yckxnwzq

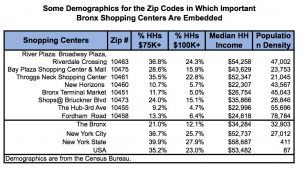

Are retailers flocking to The Bronx’s old, well-known urban corridors? Not so much. To pedestrian and mass transit oriented locations? Some, but far from most. Or to car oriented shopping centers with large parking lots or large parking garages that are cheek to jowl with major highways? Now, we’re surprisingly on the yellow brick road. Let’s take a closer look and see what I mean.

Are retailers flocking to The Bronx’s old, well-known urban corridors? Not so much. To pedestrian and mass transit oriented locations? Some, but far from most. Or to car oriented shopping centers with large parking lots or large parking garages that are cheek to jowl with major highways? Now, we’re surprisingly on the yellow brick road. Let’s take a closer look and see what I mean.