By N. David Milder

Introduction

This is the second of a two-part article on the need to be very cautious when doing or using a leakage analysis. Part 1 focused on the analytical issues associated with this economic development research tool. It can be found at

https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2016/09/retail-leakageleakage-analyses-should-be-treated-with-great-caution-by-analysts-and-end-users-analytical-issues.

This article will focus on the problematical data too often used in leakage analyses.

GIGO is an acronym well-worth knowing. It stands for Garbage In, Garbage Out. Too many leakage studies are very problematic because the data they use are very questionable. This is often not the result of data suppliers being slovenly in their data gathering or analysis – although sometimes, it is – but because getting information about small and medium sized firms’ sales, workforces and finances can be very difficult. To counter this problem, the leakage market data firms sometimes will try to use business census and related data to estimate the sales of the firms in the major NAICS codes that have been identified in a study area. Their resulting estimates are not based on primary research and have a number of degrees of separation from the original firm level data that is usually unknown to the data purchasers. Different research firms will have different methodologies for making these estimates. Which, if any of them, produce accurate estimates about NAICS retail categories’ sales is a key question. Unfortunately, I have not seen any studies that validate the accuracy of these estimates. This suggests caution and prudence in their use.

A Good Starting Point for the Discussion

The table above is a good starting point for this discussion. It shows the results of the leakage analyses generated by Nielsen and Esri for a city in the West that has a population of about 30,000. These two respected private firms provide a lot of the demographic and business data used in the economic development field and the table is representative of the leakage analysis data they produce. They certainly are not the only ones that generate the data used in a leakage analysis, but because of their affordable prices and easy online access, they are used by many EDOs (mostly by their consultants) looking for such information.

The table’s first column shows the NAICS retail categories being analyzed. Leakage analyses subtract retail sales in the study area from consumer expenditures. If the expenditures exceed sales, there is a leakage. Conversely, if sales are larger than consumer expenditures, there is a surplus. Columns three-five provide the data on consumer expenditures, store sales and leakages/surpluses for each category. The data in columns three and four are estimates – these firms have not directly surveyed the residents of City XYZ about their expenditures or the retail stores about their sales. That’s one reason why their leakage analysis reports can cost $50 and not $25,000. The data in column five are simply the results of subtracting the data in column four from those in column three.

Given that the numbers in column five are supposed to facilitate an understanding of economic growth potentials and possibly an assessment of the market viability of substantial private investments, looking at the table probably leaves the reader disturbingly confused. While there is agreement in direction (i.e., leakage or surplus) and quantitative closeness in some categories, e.g., gasoline stations, furniture and home furnishings, on many others the size of the leakage/surplus differs substantially, e.g., food and beverage stores, or conflicts on direction, e.g., health and personal care stores and eating & drinking places.

Looking at the estimated data in columns three and four, there is an even more divergent pattern. The estimates of both consumer spending and stores sales are in most cases substantially different. These two market data-producing firms are obviously using very different methodologies and/or formulas to generate these estimates.

How, then, do we know which, if any, of these leakage estimates can be trusted?

An Example of the Explanations They Provide

If you call these firms or look online for explanations of how they generate their estimates, they may use quite a few words, but seem nonetheless not very transparent. Here, for example, is how ESRI in “2014 Methodology Statement: Esri Data—Retail MarketPlace,” a 2014 white paper,” described how they estimated retail sales:

“Estimates of retail sales begin with the benchmark, the 2002 and 2007 CRT (Census of Retail Trade) from the US Census Bureau. Trends from the economic censuses are used to update the base along with Esri’s extensive portfolio of demographic and business databases. These include commercial and government sources such as the Dun & Bradstreet business database and economic statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Supply estimates also incorporate data from the Census Bureau’s Non-employer Statistics (NES) division. Smaller establishments without payrolls, such as self-employed individuals and unincorporated businesses, account for a small portion of overall sales. However, these businesses represent more than half of all retailers in the United States. Their inclusion completes the report of industry sales.

Esri’s model captures economic change by first differentiating employer and non-employer sales growth. Multivariate statistical techniques are used to model data that is subject to disclosure issues in CRT and NES. Sales estimates have been recalibrated against the Monthly Retail Trade (MRT) survey and independent sources to address the disparities that can exist between independent input data sources. This methodological improvement yields a more precise estimate of the retail sales attributable only to domestic households.

Esri licenses Dun & Bradstreet’s business database, which also provides sales for the retail market. Although Esri utilizes this database in the derivation of small-area estimates, the methods differ. Esri estimates retail sales only to households for implementation within the Retail MarketPlace data. Additionally, Esri relies heavily on data from both the CRT and MRT to improve estimation. Furthermore, the Dun & Bradstreet business data file is reviewed and cleaned to improve data content. All estimates of market supply are in nominal terms and are derived from receipts (net of sales taxes, refunds, and returns) of businesses that are primarily engaged in the retailing of merchandise. Excise taxes paid by the retailer or the remuneration of services are also included, for example, installation and delivery charges that are incidental to the transaction.”

This explanation shows that Esri s methodology is a rather complicated, multi-step process, which involves quite a few data sources and data manipulations. Part of those complications is the result if its recognition that the estimates based on one data source or another are in need of improvement.

Dun & Bradstreet (D&B) and MRT data are needed because:

- The business census data are aggregated to such geographic units as states and counties that are not congruent with the non-legally defined boundaries of many study areas. Addressed based D&B data can be aggregated to the needed geographic boundaries.

- The business census is done only every seven years and the actual data are only released two to three years after it is taken. Depending when they are used by outside analysts, the business census data can be three to six years old. The census data cannot be depended on to detail what businesses are there and what they are like. The D&B data are supposedly more recent and able to establish who is there now. ESRI’s methodology recognizes the importance of knowing how many firms by size there currently are in each retail NAICS code in a leakage analysis study area. The NES data are used to address the presence of small firms.

On a key question, whether and how Esri uses D&B’s data on firm sales, Esri’s white paper is unclear.

My take aways from Esri’s explanation of how estimates of retail sales are made are that it

- Reveals the sources of some of the data they use, e.g., the Census Bureau, BLS, Dun & Bradstreet. However, they do not detail the data obtained for each retail firm (e.g., name, NAICS code, sales, number of employees) or, very importantly, how these data may have been statistically manipulated to produce their estimates. This is understandable to the degree that their methodology provides a competitive advantage over their rivals and therefore needs to be kept confidential. Nevertheless, it makes assessing their estimates more difficult.

- Additionally, and perhaps even more importantly, Esri provides no indication that they have validated their estimates, i.e., shown that their estimates are accurately measuring what they are supposed to be measuring, or that they even made an attempt to do so. How, then, can we know that their methodology is sound? How can we have confidence in them?

- Is a complicated methodology with many steps. I was taught that every time basic data are manipulated or added to there is a potential for a new error factor to be brought in. Esri has added steps to its methodology to overcome some known errors. Whether they are successful or simply add new errors is unknown.

I have not found any better explanation from Nielsen or its corporate predecessor Claritas about how they estimate retail sales.

A Closer Look at Basic Supply Side Information: Retailers –Their Number, NAICS Codes, Sizes and Sales

Accurate basic firm level data are absolutely essential to an accurate and useful to a traditional leakage analysis. Having directed numerous surveys of business firms, especially retailers and those prone to renting office spaces, and conducting countless personal interviews with business owners and managers in the USA and France, I am well aware of the difficulties involved in getting reliable data from business firms. This is especially true for the sales and finances of small and medium-sized operators.

As the following quote from Mike Stumpf indicates, I’m not the only one that questions the verisimilitude of the firm-level data that is often the foundation of a leakage analysis. From a recent email, here is Mike’s description of how ESRI looked at one area’s business mix:

“ESRI looked at the area’s business mix, then talked about the very large number of establishments in the financial sector. ESRI’s database lists every ATM as a business establishment! A grocery store with a deli, pharmacy, and liquor store can be listed as four different businesses, each with its own estimated sales, but then they do not pick up the restaurant in the Mexican grocery. Their sales estimates for one Mexican bakery were under $100,000, but they actually do more than that in a single month.”

Both Nielsen, ESRI and other leakage analysts obtain basic data about the stores in a study area from other market research firms, such as InfoUSA, Dun & Bradstreet or, its subsidiary, Hoovers, etc. that focus on firm-level data gathering. Nielsen and ESRI combine that info with data from the economic census and other sources to produce their estimates. In a sense they are heaping estimates upon estimates, with each potentially having unknown error factors that may combine through addition or multiplication.

Over the past three decades my company, for our client’s downtowns, has purchased establishment level data from some of the same business market researchers that have supplied firm level data to ESRI and Nielsen. On occasion, we obtained such data from local economic development agencies. Our experience with those data made a deep impression because:

- There were usually error factors of 20% to 40% in the listings of firms. The errors, as might be expected, were most frequent among the really small firms that have a high probability of failure and turnover, but some of a downtown’s larger retailers were too often also omitted or listed after they had closed. We have seen annual retail churn rates in our clients’ downtowns (they include newcomers as well as closures) that can range between 5% and 30%. Unless these gatherers of firm-level data research businesses annually, which is very expensive, there is a high probability that their collected facts will be out of date. The year-to-year errors can really add up.

- The Retail NAICS codes often may be wrong. Our discussion with one of the businesses that gathers firm-level data revealed that the downtown firms themselves were surveyed and provided their NAICS code(s). They were aware that errors were frequent. They attributed this to a difficulty in getting knowledgeable executives to respond to their survey. My review of the NAICS codes listed for retailers in the downtowns we bought data for frequently found numerous questionable codes.

- I have supplied the NAICS code for my firm in the business census and to insurance companies and found out what many of the not large downtown business owners have told me over the years: selecting the right NAICS code isn’t easy, its takes too much time, and consequently, they just put down whatever is easiest to get the task done. Some reported giving the job of responding to the business census and enquires from firms like InfoUSA to their secretary or assistant or salesperson. I suspect that there are even substantial NAICS code errors in the US Business Census returns — especially from respondents who are the types of independent retailers found in our small and medium-sized downtowns and urban ethnic neighborhood commercial centers. DANTH, Inc. has conducted many surveys of businesses over the years, including the largest corporations headquartered in Manhattan, those in the healthcare industry, manufacturers in Nassau County, NY, etc. We quickly found there was a tendency for high-level executives to avoid responding to our survey. They felt it was a waste of their time.

- Getting accurate firm-level retail sales data is really, really difficult. In addition to the surveys mentioned above, DANTH has also done numerous surveys of downtown merchants. Unsurprisingly, we found that there is strong resistance among most independent downtown merchants to providing such information. Interestingly, they sometimes reported that, off hand, they don’t know that information. The managers of the national chain stores also are loath to reveal their sales statistics. Many downtown managers – probably most – can attest to the difficulty of obtaining such information.

- One of the business market researchers reported to me a few years ago that they have similar challenges getting information about a firm’s sales, workforce and finances. For the national chains, they use the chain’s average store’s sales. For the independent merchants they ask for the number of employees – which they said small retailers are more willing to provide – and multiply that by the average sales per employee for that NAICS code in the state. D&B is in the credit rating business, so small and medium-sized retailers who are concerned about their credit rating have an incentive to respond to D&B inquiries.

Getting basic information about small and medium sized business is a tough job, fraught with potential errors. Given that this type of information is such a basic building block in the often-complicated process of estimating the retail sales of a study area, it seems wise to treat such estimates with caution and prudence.

DANTH, Inc. has used leakage analyses generated by Claritas Esri and UWEX. In each instance, I created small tests of the data. Sometimes running a leakage analysis on a small of part of the study area enabled a comparison of the number of firms with my visual counts. If a NAICS category was identified as being very strong, I tried to verify that by visual inspection and interviews with local business operators. In a project in Sherwood, WI, a fast growing community, I thought that both the demographic data and the leakage analysis of one provider were badly out of date. Instead, I used the UWEX Gap Calculator and data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. On another project, one of my little tests was to see if the leakage analysis had captured the sales of a food operation inside of a convention center. Finally, there is the “making sense test.” Sometimes I’ve looked at one of these leakage analysis reports and felt it just does not make sense. It just may be that the numbers do not jive in my mind with what I saw touring the study area and what I heard from local business people and economic development officials. Reports that fail the making sense test cause me to take a much closer look at the situation.

Sales Tax Data. In a number of states, retail sales tax information sorted by NAICS codes are gathered and published for the state, counties and sometimes the cities. These data are potential analytical gold for those researchers who find those geographic units congruent with their study area. Even when they are not, the validity of such data may provide a strong foundation for making needed extrapolations for the non-legally defined study areas.

Most of my project experience has been in states that do not provide such information. On the two occasions when I did projects in such states, I encountered some problems that impeded my use of the sales tax data. In one state, the sales tax is applied to only a portion of the merchandise in various NAICS categories and we could not determine what those percentages were. In the other state, the data for the counties were only provided at the two-digit NAICS code level, e.g., that of the entire Retail Trade category.

However, I have been told by some economic development consultants in California whom I respect that the state’s sales tax by NAICS code data enables them to produce more reliable leakage analyses.

Avoiding the Need for Retail Sales Estimates

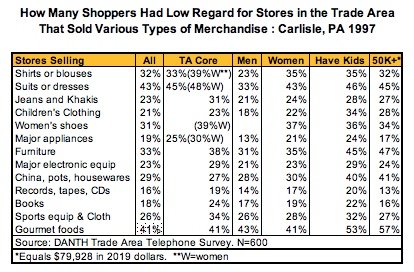

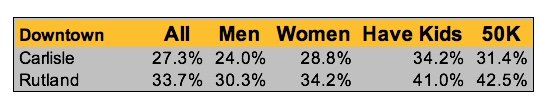

In the 1990s and early 2000s, instead of the usual leakage analysis, DANTH, Inc. used an approach based on the consumers’ satisfaction with the retail services in their market area. We thereby solved the unreliable retail sales estimates issue by avoiding the subject. Our analysis focused solely on the consumer. Back then, response rates to our telephone surveys were far more acceptable than today’s 30% or so and we asked respondents if they were satisfied with the stores within a 15 minute drive in each of the higher level retail SIC or NAICS codes. Those that were dissatisfied we deemed as probable out-shoppers and open to being attracted by new retailers within the trade area. We also knew from the survey about these dissatisfied shoppers’ incomes, education levels, age cohorts, etc.

Using consumer expenditures potentials generated by ScanUS, Esri or Claritas we also provided estimates of the consumer expenditures for some of the products associated with each retail SIC/NAICS code. The expenditures of the “underserved” shoppers were, in a sense, up for grabs and prone to being spent out of the trade area. Back then we were not able to match completely BLS product categories to NAICS codes as can now be done. Our retail growth strategies were based on capturing these up for grabs shoppers and a sample of their retail expenditures.

This approach is sort of like a leakage analysis, though not the same. However, it enables an analyst to answer the same important retail growth questions, with far fewer questions about the validity and reliability of the data used.

DANTH has not used this approach recently because the cost of a really good telephone survey has become unaffordable and their findings less reliable, while the use of lower cost non-panel online surveys have serious sample issues.

Of course, others have used local surveys to ask respondents about whether they mostly buy various products in town, out-of-town or online. That, too, tells you about the leakage of shoppers and avoids the need for data about retail sales. Here, again, being able to do an affordable survey with a representative sample is a critical question.

My guess is that within the next 10 years online survey techniques will solve the sampling issue and affordable surveys will be possible. Then researchers will be able to answer the questions that leakage analyses are intended to address without needing to know about local retail sales or complicated methodologies for estimating them.

The Demand Side – Consumer Expenditures by NAICS Category

BLS Based Approaches. As I have written elsewhere, the best way of obtaining reliable, acceptably accurate data on how consumers spend their money is to survey them. However, such surveys require substantially more methodological skills and resources than most other kinds of surveys. For many consumer items, the relevant information must be obtained close to the points in time when the expenditures are made, lest memories of them quickly fade. For example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) probably sets the gold standard for this type of research and it has half of its 14,000 survey respondents keep diaries of their expenditures and interviews the other half 5 times over 15 months. In contrast, I’ve seen many inept downtown and Main Street surveys that ask about shopper expenditures that are oblivious of the challenges involved, have no where near the rigor of the BLS surveys, have relatively few respondents and their results aren’t worth the paper they are printed on.

While the BLS expenditure data are solid and a good starting point, using them to inform estimates of consumer expenditures in a leakage analysis study area presents a number of barriers that must be overcome:

- The BLS uses categories to order its data that are product oriented, about the things people buy not the kinds of stores consumers buy in. The demand side retail sales data are ordered by the NAICS codes that are about the characteristics of aggregations of retail stores. To be useful in a leakage analysis, the BLS data have to be “crosswalked” into the NAICS categories. Such data crosswalks are enabled by a list of the products that are typically sold in the different retail NAICS codes that was produced by the Census Bureau. Using the list can take a lot of effort. Computerizing the list makes things easier, but also takes resources. Both Nielsen and Esri do these data coding crosswalks. This data crosswalking is a possible opportunity for errors to enter the analysis, but I think the probability of that happening are relatively low.

- The geographies used by the BLS are far, far larger than the size of any retail leakage study area. The 14,000 respondent BLS sample is still too small to provide enough respondents to be directly used even at the state level of analysis; the sample would average only about 280 respondents per state. Consequently, some methodology is needed to make estimates of consumer spending within retail leakage study areas that is based firmly on the BLS data. Both Nielsen and Esri have developed methodologies to make such estimates based on the BLS data. My research experience says these research tasks have significant opportunities for errors to enter into the analysis.

- Different types of people have different spending levels and patterns and different retail leakage study areas will vary in the kinds of people that live in them, e, g., by income, education, race, lifestyle group. The BLS data based estimation process needs to be able to adjust expenditure estimates by taking these population differences into consideration. Both Nielsen and Esri use their demographic and lifestyle segmentation databases, Prism and Tapestry, to make these adjustments. My research experience again says these research tasks have significant opportunities for errors to enter into the analysis.

The data presented in the table earlier in this article about City XYZ shows big differences in Esri’s and Nielsen’s estimates of consumer expenditures. This suggests that while they both are trying to address the problems just enumerated above, their methodologies vary significantly. Again we are posed with the problem of whose estimates, if any, should we trust?

The BLS data covers household expenditures. Used in a leakage analysis they inform only about the expenditures of study area residents. They do not appear to inform about the expenditures of day and overnight tourists and non-residents who work in the area. Yet, accurate estimates of retail sales should include the sales dollars from those types of customers. For many downtowns, the non-resident customer base can be extremely important. There consequently seems to be an imbalance between the customers included in the analysis on the demand and supply sides. Bill Ryan has recently upgraded UWEX’s Gap Calculator to incorporate data on the expenditures of tourists and people working downtown. Others should follow suit.

Also, of increasing importance, the BLS data does not tell us whether consumer expenditures are being made in brick and mortar shops or online. The total of online retail sales now only accounts for about 6.5% of all retail sales nationally. However, as can be seen in the above table,

- By 2017 it is anticipated, if trends continue, that e-commerce will account for 50%+ of the sales for music, videos, books, magazines, computer hardware and software, toys and games, electronics and appliances,

- By 2017 e-commerce is projected to account for 25%+ of the national sales of furniture, sporting goods, office equipment and supplies, clothing, accessories and footwear.

The vast majority of online purchases will be going to retailers based geographically outside of the retail leakage study area, perhaps across the country or even on another continent, yet they are very close because they can be reached from a living room chair almost instantaneously via a smartphone, tablet or computer. The online purchases are, of course, leaked purchases. The important question then becomes do local merchants have a real chance to recapture these dollars? The strong trend now is for online sales to grow at a rapid pace. Younger Americans, especially the Millennials feel very much at ease with making online purchases and they will be growing in number. Older folks are getting more accustomed to buying online, but not like the younger age cohorts, and many of them will soon fade away. Consequently, a strong argument can be made that, for the foreseeable future, it will be much harder for local brick and mortar merchants to win back dollars spent on the internet than for dollars spent in other brick and mortar shops located beyond their trade area’s boundaries.

If this is the case, then knowing about how many consumer dollars in a study area are going online is, in effect, identifying “dead dollars” that now are well beyond the reach of local retailers who really have little hope of recapturing them – unless they, too, are able to become strong competitors on the internet. Unfortunately, this is the type of information that many downtown leaders need to know, but don’t want to hear.

None BLS Approaches. Leaders of EDOs in many small and medium sized communities may want a leakage analyses done for their downtown, but the don’t have a lot of money to pay for a consultant. Some consultants and economic development organizations have constructed leakage calculators that can be used by EDO leaders or their staffs either for free or for little cost. These builders of these calculators do not have the funds that take the BLS data and crosswalk then into NAICS codes, or to generate expenditure estimates at the study area level, or to adjust such estimates through the use of a lifestyle database. Instead, they take a simpler and less expensive approach:

- They take the retail sales by NAICS code at the state level and adjust them for inflation

- Then they divide those sales numbers by e the population of the state to get per capita sales per NAICS code at the state level.

- Then they treat these per capita sales estimates as measures of per capita spending. They identify the population of the study area in question and then multiply the NAICS per capita sales estimates by that population number to estimate total consumer expenditures by NAICS codes for the study area.

- They then identify the median household income in the trade area and adjust the consumer expenditure estimates accordingly.

In a lot of ways this is a simpler and easier way of estimating consumer expenditures in a study area than how Nielsen and Esrsi do it. I’ve used the UWEX Gap Calculator and can attest that its easy to use. It’s intended users are small and medium-sized downtowns, where local leaders can input their own data about the retailers in their trade areas.

The use of sales data at the state level to estimate consumer expenditures at a study area level may raise a few eyebrows. It did mine. Since the state retail sales data includes tourist sales, those dollars are also finding their way into estimates of resident retail expenditures and inflates them inversely to the actual flow of tourists through the study area. The theoretical explanation for it escapes my understanding. But, can Nielsen and Esri prove that their estimates are any better?

Given that there is no evidence that the gap calculators do any worse than the leakage reports the big private market data firms put out, who’s to say they are not worth considering. The price is right. Moreover, they are methodologically rather transparent: it’s easy to understand how all the estimates are being made.

Some Final Comments.

To properly do our research we need to live in the real world and in that real world we most relay on doing secondary or tertiary levels of analysis on primary data collected by someone else. Professionally, we should have been trained to understand that we must be very cautious about how we do our secondary analyses and transparent about our methodology when we present our findings to others. We need to be even more cautious about how we accept the secondary analyses done by others – especially when their methodology is not transparent and their findings have a significant number of apparent errors and conflict with the findings of other analysts.

That is why I argue that the estimates of retail sales and consumer expenditures generated by most leakage analyses should be treated with caution and used with prudence.