Downtown Revitalization:

Some of N. David Milder’s Perspectives Columns

Column Index

Published in the Downtown Idea Exchange

Presented on this website with permission of Alexander Communications

Downtown Retailers Shouldn’t Settle for Good Enough

Time-squeezed Americans Need Convenient Downtowns

Creating a People-watching Niche

The Politics of Downtown Redevelopment Projects

Making Membership Buy-ins Easy

Retail Raptors and Raptor Niches

Nail, Hair and Skin Salons: Bane or Boon?

As We Leave the Recession, Affordable Retail Rents Are a Revitalization Imperative

The Growing Importance of Multichannel Retailing

Downtown Retailers Shouldn’t Settle for Good Enough

By N. David Milder

DANTH, Inc.

July 2003

I’ve been in the downtown revitalization field for more than 25 years, and the people who consistently give me agita are, to use a term coined by Herbert A. Simon in his Models of Man, the “satisficers,” meaning the merchants who want to earn personal incomes or store revenues that are just “good enough.” The reason for my heartburn is that downtown revitalization means change, and satisficers are anti-change agents who dread innovation and shun any risk!

Unfortunately, too many of the downtown independent merchants I know are “satisficers.” Satisficers can be contrasted with maximisers, who seek the biggest, or with optimizers, who seek the best. Satisficers, behind all their typical merchant complaints, are doing okay financially and won’t put in the time and effort required to make more money. In my experience, satisficers are the root of a whole syndrome of downtown problems, such as poor marketing, weak merchandising, marginal customer service, and downtown manager burnouts.

No desire to grow

The satisficer’s perspective is exemplified by the owner of an apparel store in an urban shopping district in New York City. He refused to participate in a BID advertising program because it would bring in too many customers, and he then would need more space! Similarly, the owner of a restaurant in a suburban downtown in New Jersey also refused to advertise, for fear that it would bring in more customers, which would mean she would have to grow and lose direct control of her operation.

Satisficers like bankers’ hours

Trying to expand downtown operating hours into the early evening brings out the satisficers in droves. Based on my firm’s numerous surveys of downtown trade area residents and field observations of store operating hours, I estimate that a shop open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and Saturdays is closed when 40 percent to 50 percent of all comparison shopping trips occur. Even when informed of this, the satisficers insist on closing by 6 p.m. — and you can spit blood trying to convince them to do otherwise. Rational argument does not work.

I’ve found that trying to get satisficers to improve their marketing, merchandising, and customer service is also usually doomed in terms of numbers. At most, 5 percent to 7 percent of the satisficers can be “educated.” Although these numbers are small, you might convince one or two key merchants, so the educational effort can still be worthwhile. Also, because they usually are paying — and complaining — members of the downtown organization, you have an obligation to try. Politically it’s a smart thing to do.

Attracting the strivers

The best strategies for dealing with the satisficers problem are redevelopment and recruiting strivers. A number of my clients have pursued redevelopment projects in part to get rid of existing satisficer merchants and to bring in retail chains or independents who are strivers instead.

Strivers bring a competitive edge

Strivers are independent merchants who are intent on increasing or maximizing their sales and incomes, building a very successful store, or creating a chain. Many immigrant entrepreneurs and merchants committed to customer service, advertising, and good merchandising are strivers. Recruiting strivers requires a lot of time and effort to research good merchants in other locations and interview them and those who have worked with them.

I’ve found that this kind of recruitment is harder than recruiting retail chains, and ultimately more important, because it’s the quality independents who give a downtown its distinctiveness and competitive edge.

If you go to conferences on improving downtown retailing, the focus is always on attracting the chains — little is said about the strivers. It’s about time that this changed.

Time-squeezed Americans Need Convenient Downtowns

By N. David Milder

DANTH, Inc.

July 2003

I am writing this article in Las Vegas (pop. 478,000), where hotel owners demonstrate an impressive ability to manage the way guests spend time. They want customers to spend as much time as possible in the casinos, so hotels are carefully designed and programmed to accomplish that goal.

Downtown leaders can learn much about the importance of customer time management from the Las Vegas casino owners. Time has become a crucial factor in downtown revitalization, because the amount of leisure time enjoyed by the average American has shrunk 37 percent since 1973. Increased time pressure now is one of the biggest determinants of consumer behavior, and because of it Americans are:

- More interested in living within a 30-minute commute of their work places — understandable since Americans spend an average of 1,900 hours a year at work, which amounts to about 20 more working days annually than 25 years ago.

- Shopping less at malls.

- Spending less time shopping.

- Engaging in more quick, single-task shopping trips where “quick in and quick out” is the operating principle. While the same consumers also still engage in the longer, multitasked shopping trips, they are not as frequent. My field observations also suggest that shoppers are more willing to pay more for a product if they spend less time acquiring it.

- More interested in living, shopping, and working in downtowns.

- Finding it harder to spend quality time with spouses and children and, consequently, searching for Central Social Districts — which are often most easily established in downtown environments.

- More inclined to eat in restaurants or buy take-out meals — 47 percent of the money Americans spend on food now goes to restaurants. Tim Zagat cites this as the BATH phenomenon; i.e., the restaurants and take-out places are a Better Alternative To Home. Often these restaurants and take-out places are in a nearby downtown.

- Time pressures are good for downtown

Overall, the growing time pressures faced by the American consumer have been a positive force for downtown revitalization. However, unless downtown leaders take fitting actions, that situation can quickly erode. Appropriately serving the consumer’s time needs is an essential component of both customer satisfaction and creating an appealing downtown image. There are many functional areas where this can play out, but here are some of my observations about how time pressures are impacting downtown parking problems.

An intercept survey done in the Cedar Lane Shopping District in Teaneck , NJ (pop 39,000), found that most shoppers spent less than one hour in the district. Given the variety and quality of the shops, there was little incentive for browsing shoppers to spend much more time. The movie theater and restaurants were the biggest draws for visitors staying longer, but patrons came mostly in the evening, after the other shops closed. I strongly suspect that the same shopper “time expenditure” pattern exists in all but the largest and strongest downtowns.

Providing parking for the time-squeezed

In most downtowns, the focus of parking studies is on the creation of more capacity, usually in the form of surface parking lots or decks. These parking facilities are best suited for shoppers who need to spend at least an hour on their trips — just getting in and of the facility and walking to and from their downtown destinations can take up a big chunk of time. Rarely have I seen comparable attention paid to the parking needs of shoppers who need just 15–30 minutes to accomplish their tasks. Downtown parking must be designed to support the consumer, whether he or she is in a browsing/shopping mode or in the “quick in, quick out” mode.

One way to respond to the “quickie” shopper is to have some well-designated, on-street spaces metered for no more than 30 minutes. Effective enforcement will be necessary to make these spaces work as intended. A side benefit of these actions is the additional friction they create for downtown employees who feed the meters.

If quickie shoppers cannot find a space on the street within steps of their retail destinations, then it is important that the downtown prevent a long search for a parking spot. Easily identified and legible signage indicating where the closest lots are located would be helpful — even more helpful would be information about their capacity and, better yet, how many vacant spaces they have. About a decade ago a transportation planner told me about an electronic signage system for parking lots that could communicate information about available spaces. Such signage systems are common in European cities, but I have never seen or heard of one in the United States.

Downtowns ignore consumers’ time pressures at their own peril.

Since the publication of this article the author has seen an

electronic signage system in the garages at The Grove in Los Angeles.

Parking Availability Sign at The Grove

Creating a People-watching Niche

By N. David Milder

November 2003

About a year ago, I was sipping an espresso outside of the Café de Flore on the Boulevard St. Germain in Paris, when I had an epiphany about downtown entertainment niches. In downtowns known for their truly urban flair, an informal type of entertainment takes place in which people, just by being themselves, entertain each other. This kind of informal entertainment seems to be maximized when a downtown can attract interesting people and provide opportunities for visitors to engage in casual activities that they enjoy and that engross and amuse observers.

Cafes as outdoor theater

It occurred to me that Café de Flore was not just a dispensary of food and drink but also an important entertainment venue. Right there, a lot of things were grabbing my attention and amusing or moving me. Most of all, it was the people I could observe — those sitting at nearby tables, the pedestrians strolling by, the waiters, and even some car drivers displaying rather unique maneuvers.

Gardens and parks

While the Tuileries Gardens, in the heart of Paris, are breathtaking, I am always amused by the other people who are visiting them. You can watch lovers, young and old; children on a carousel and their adoring parents minding them; model boats sailed by youngsters in a pond; folks eating an ice cream or other snacks; fellow tourists exploring, gawking and often behaving in strange, but nonthreatening, ways; and just people watching other people. The park is like one big stage set on which the visitors are both the performers and the audience. The carousel, model boat pond, snack kiosks, and chairs provide opportunities for visitors to perform and entertain the other visitors; they are like a self-programming entertainment infrastructure.

In my opinion, this is what great public spaces do: they provide opportunities for people to engage in activities that they enjoy and that also interest and amuse nearby people-watchers. Think of the ice skaters drawing the ever-present crowds above the rink in Rockefeller Center. Similarly, in Manhattan’s Bryant Park, you’ll find young men and women seated and watching each other and chess players, who always attract an audience. Greenport, NY, a much smaller community, has used a carousel, outdoor concert facility, and waterfront location to create another wonderful public space where people can entertain each other.

Restaurants

Dining in a Parisian restaurant, to me, is like being in a show where I have a role. Because they are Parisian, they have a kind of exotic allure. And the presentation of the food, from the sommelier uncorking a wine bottle to a fish being filleted or crepes suzette being flambéed at your table, is filled with skillful, amusing, and theatrical performances.

Bringing it home

You don’t need a big cultural complex like Lincoln Center or an entertainment mall like Cocowalk to have a successful downtown entertainment niche. Moreover, you don’t even need a cinema, a legitimate theater, or a concert hall.

Downtowns in the United States, be they large or small, can have strong and successful entertainment niches if they provide opportunities for people to entertain each other. Such opportunities can be fostered by such facilities as:

- Outdoor ice and/or inline skating rinks

- A carousel

- A model boat pond

- A children’s pony ride

- Tables where people can play chess, checkers, or dominoes

- A Wi-Fi hotspot to access and cruise the Internet on laptops

- A place to catch the sun — a favorite pastime for office workers and young tourists in the spring and summer

- Places to buy food and eat lunch alfresco

- Outdoor cafes for sipping coffee and eating snacks

- Downtowns that can successfully attract people whom the general population might consider strange, but nonthreatening, will also be entertaining. Such groups might include ethnic groups new to the community — almost always teenagers with their avant-garde clothing styles and body piercings.

Theaters, movie houses, and concert halls can be great for any downtown, but without the kind of people entertaining each other with activities like those described above, a downtown’s entertainment niche is liable to be dormant most of the time, when facility doors are closed. People-to-people amusements can occur all day long.

The Politics of Downtown Redevelopment Projects ©

By N. David Milder

March 15, 2004

(An expanded version of this article appeared in “Making Business Districts Work: Leadership and Management of Downtown, Main Street, Business District and Community Development Organizations,” published by the International Downtown Association during in 2006.)

Increasingly across the nation, the name of the game in downtown revitalization is shifting from district management to redevelopment. While downtown leaders usually welcome their growing involvement in redevelopment, all too many initially fail to recognize — often, until it’s too late — just how “political” such projects can be. Consequently they often are very reactive and ineffective when the inevitable political brouhahas emerge.

The fact is that redevelopment projects, by their very nature, usually motivate some residents and businesspeople to oppose them and often there are community groups ready to organize, mobilize and finance this opposition. So, if your downtown is serious about redevelopment, your leadership should be ready and able to politically navigate such situations.

Some Do’s and Don’ts

Here are some suggestions for handling a number of the political problems associated with downtown redevelopment projects:

Have an areawide plan

Some years ago, on assignment to Regional Plan Association, I interviewed most of the big developers in New York City to find out what would get them more involved in the outer borough downtowns. Their overwhelming answer was for the city to prepare areawide plans that would designate development sites, with their allowed uses and densities and establish environmental, parking and traffic parameters for the surrounding areas. Such plans may be the gold standard for dealing with redevelopment project approvals. For the developers, comprehensive areawide plans mean that most of the important potential conflicts that a project might provoke are resolved before the developers become involved — and this promises huge reductions in their risk and front-end costs. But for downtown leaders and/or city redevelopment officials, creating such plans requires money, time and a strong consensus-building process — assets they frequently lack. Also, it is almost impossible to create an areawide plan after a proposal for a redevelopment project is placed on the table.

Prepare a compelling case

All too often downtown leaders are so involved in attracting a developer and getting the deal done that they don’t pay enough attention to creating a compelling brief for their project. Try to figure out ways to make the project’s benefits immediate and tangible to residents– residents with a detailed understanding of how a redevelopment project can help them will be more motivated to actively support the project. Describe, for example, how the project will protect against property tax increases, add jobs, create affordable housing for local residents, bring in retailers that the community wants, etc.

Campaign for the project

This campaign should begin well-before any pivotal make-or-break vote about the project occurs. In addition to well placed stories in the print and electronic media, this should also involve presentations to key community groups and decision-makers

Mayor’s roles. Some mayors want to be the city’s redevelopment guru, energizer and/or deal-maker. Almost invariably, this creates strong political turbulence. Citizen support for the mayor’s redevelopment project(s) becomes inseparable from their political support for the mayor. Ideally, you want the mayor to be able to support a project without the project being perceived to be under his or her political ownership. The most effective mayors I have worked with in downtown redevelopment tended to be strong public advocates of revitalization and the guardians of the redevelopment decision-making process, assuring its staffing, financial resources and smooth and effective functioning, while demanding real accomplishments from its participants.

Don’t forget city council

In many municipalities, the city council will be making critical decisions about downtown redevelopment projects. Council members will have to incur the political costs that supporting the redevelopment project might entail. They are more likely to withstand political slings and arrows if they are brought into the redevelopment decision-making process early, rather than later. For example, Bob Benecke, the city manager of Englewood, NJ, has held workshops on downtown revitalization for council members and he frequently briefed them on potential projects in the confidentiality of caucus sessions to test and mobilize their support.

Try to mobilize civic groups

Neighborhood groups from areas not immediately adjacent to a redevelopment site sometimes may have good reasons to support a redevelopment project. A good illustration of this occurred in Garden City, NY, which is run politically by four residential property associations. A few years back, one property association – the one closest to the main commercial strip– objected to the implementation of long-planned parking improvements that were needed to assure the financial health of some key office buildings. Their objections prevailed until the other property associations realized that this would result in more of the tax burden being shifted from downtown commercial rate payers to residential rate payers throughout the town.

Don’t hold large public meetings

In large public meetings about redevelopment projects the group dynamics usually encourages participants to be critical and vituperative. Rational discussions and civil exchanges of information are minimal. Project proponents never convert those on the fence or opposed to the project. On the other hand, these meetings often do galvanize, energize and strengthen project opponents.

Use small group meetings for public input. A more effective approach for public outreach is to meet with small groups, especially with the leaders of significant neighborhood and civic associations. In these smaller meetings the conversation cannot be one-sided — be prepared to listen and negotiate. Also, look to establish common grounds.

Avoid long lists of projects

Downtown experts have long admonished downtown leaders to take a comprehensive approach to revitalization. Sometimes this advice impels downtown leaders to want to publicly identify every possible downtown redevelopment project so they can show their constituencies just how thoroughly they are doing their job. One mayor I know insisted on presenting to his community a long and detailed list of recommended downtown redevelopment projects. If one project is going to stimulate public opposition, you can image how much agitation six or seven projects can ignite– and they did! A more prudent approach is to move project by project, using one project’s success to garner support for additional redevelopment projects.

Chose savvy developers

Look for developers who are willing to try to buy out property owners and don’t rely entirely on public takings. Conversely, the municipality should try to minimize the number of properties on which it has to use its eminent domain powers in order to assemble a redevelopment site.

The need for redevelopment in many downtowns, be they large or small, is undeniable. Moreover, for the first time in decades, there are scads of developers who are looking for downtown projects. Equally undeniable, is the need to have the community support these projects. While redevelopment projects, by their very nature, may engender conflicts, the key factor is not that such conflicts might occur, but how they are handled.

Making Membership Buy-ins Easy

By N. David Milder ©

October 15, 2004

Over the past six months I have been active in helping to plan the agenda for Downtown New Jersey’s annual conference and in “producing” and moderating a workshop on how to reinvigorate New Jersey’s Special Improvement Districts. In the course of these activities, I have communicated with a number of downtown managers, both in NJ and NY. One of the most frequently mentioned problems was how to get their memberships to participate in and support their organization’s programs. Some downtown consultants refer to this as the “membership buy-in” problem.

These concerns resonated strongly with me. For the past 16 months I have helped manage the Bayonne Town Center (BTC), a SID management corporation in Bayonne, NJ. Over the course of that period of time, the organization had implemented a number of programs and made procedural changes that had increased membership participation and support for the BTC and its programs. Almost inadvertently, the BTC had found some important components of an effective strategy to strengthen “membership buy-ins.” An important element of this strategy was to create and utilize incentives — and do away with disincentives.

Do No Harm!

One of the primary rules in medicine is, first, to do no harm. This is also a good downtown management operating principle.

According to city ordinance, the plans for all facade and sign changes in the Town Center must be approved by the BTC’s architect. From this function, the BTC had somehow developed a strong enforcement role. Enforcement naturally entails a high probability of conflict and conflict means a high probability of hostility. While the BTC wanted to continue to advocate and encourage sound facade and sign improvements, it became obvious that our enforcement role was eroding membership support. Consequently, the BTC worked very, very hard to get the city to take on the main burden for enforcing facade, signage and sanitation ordinances. The BTC had to stop being the cop, while the city had to play more of the cop role, Now, the BTC is increasingly viewed as a facilitator in the sign and facade review process and not the organization with club that it uses to whop its members on the head. Moreover, there are now several district business operators who are communicating our more favorable image to their friends and neighbors.

Use Incentives to Implement Your Strategy

Across the nation, incentives are frequently offered by economic development organizations to implement their growth strategies. They succeed by enticing developers, retailers and major corporations to act in accordance with the organization’s plans. Car makers and consumer goods companies (e.g., P&G) offer incentives to increase sales. Incentives, can also help downtown organizations strengthen their membership buy-ins, especially in such program areas as facade improvements and marketing.

For many years, the BTC had tried to convince one particular business owner –who had a very large building facade at a very strategic location — to improve his facade. In spite of the substantial financial incentives offered by the city, about $35,000, we could not get this operator to act. Recent discussions with the operator revealed that he was concerned about the uncertainties of the total costs, which might exceed $100,000, and how to finance the portion of the costs not covered by the city’s grant. The BTC offered to help pay, on a matching basis, for an architect who would do elevations and cost estimates for improving this facade (but no construction plans or documents) and linked him to low-cost loan funds available through the Bayonne Economic Development Corporation.

Over the past year, interviews with shop and property owners revealed that one of the strongest reasons why more of them had not undertaken facade improvements, despite the generous direct assistance provided by Bayonne’s Community Development Department, was that they had not reached the stage where they were ready to apply because they:

- Had no idea of what they wanted their new facades to look like

- Or the materials that would be used

- Or the costs

- Or what architects and contractors they might use for the job.

- Moreover, these business operators are so busy that it is difficult for them, acting alone, to find answers for such questions. The BTC’s response was to try to make things easier for them:

With board approval, the BTC soon will be hiring an architect to work for “free” with five business operators and deliver to them renderings (no construction plans or documents) of what their new facades could look like along with job cost estimates and samples of materials

The BTC will also provide them with the names of local architects and contractors who could do the job.

The BTC has also developed a successful newspaper advertising program. We are doing niche and coop ads where the BTC entrepreneurs the ads — making it easier for the merchants to participate –and pays for 50% of the ads, which correspondingly lowers the advertising costs of participating merchants. Eight of nine jewelry shops, for example, signed up for the Valentine’s Day jewelry niche ad. Fathers Day advertising efforts are notoriously difficult, but we were able to get 18 district businesses signed on for our coop Fathers Day ad. A big coop ad at Christmas is anticipated. The Bayonne Urban Enterprise Zone has agreed to provide $9,000 in this new fiscal year for more niche and coop ads. This can be leveraged into an advertising effort worth at least $18,000.

There are certainly many other elements to a successful membership buy-in strategy. Two of the most frequently mentioned are good two-way communications between the organization and its members and effective membership participation in the program planning process. Nevertheless, incentives can also be an effective element. It is a mistake to think about incentives solely in financial terms. Actions the downtown organization can take to make it easier for its members to participate in such programs as facade improvements and media advertising can be as or even more effective.

Retail Raptors and Raptor Niches©

By N. David Milder

DANTH, Inc.

May 15, 2005

In a world full of Wal-Marts, Targets, Home Depots, Lowe’s, power centers and super regional shopping malls, downtowns need strong and aggressive retailers, not the meek retailers who fear competition. Recruitment efforts, consequently, need to focus on more than just filling vacancies; they need to target “retail raptors,” the merchants, large and small, who are not afraid to compete for and win market share. Unfortunately, the very way that many downtown organizations plan their recruitment efforts diverts them from looking for retail raptors.

For decades, downtown managers have been taught that an effective retail revitalization strategy must be based on a type of market research that goes by various names, e.g., gap analysis, out-shopping, or retail leakage. The basic goal of such studies is to identify the difference between the supply and demand for retail goods in a particular trade area. Demand is usually operationalized by measures of consumer expenditure potentials, while supply is normally represented by measures of retail sales. A gap (or leakage) exists when demand exceeds local supply. Recruitment efforts then are focused on attracting retailers who can fill the gap by “recapturing” local retail expenditures.

The unstated assumption on which this analysis is based is that it is easier for retailers to win “gap” expenditure dollars than non-gap dollars. Implicit in this assumption is that the gap filling retailers really will not have to fight too hard to win back this market share. Telling retail prospects that they can fill a gap is tantamount to telling them that they can, without too much effort or skill, easily succeed in your downtown. This increases the probability that meek retailers will be recruited to plug the retail gap: after all, the strong ones are not really needed and the meek will be easier to recruit.

Out in the real world, there are many successful retailers who could care less about retail gaps, leakages or outshoppers because they are prepared to fight for — and win — market share. They can range in size from mom and pop independents to large chains. These raptors certainly are not mindless — they really know who their customers are and what merchandise and services they want. They usually are extraordinarily good at this and they often invest substantial amounts of money to research this subject. The raptors will look closely at demographic and psychographic data to see if a trade area has their kind of customer. They are not too worried about the competition because they are confident, based on experiences in other markets, that if there are enough of their type of customers in the trade area, they can win enough market share for their new store to make lots of money. For example, Starbucks wants to know how many people in a market area will be willing to spend $3.00+ for a cup of coffee and views other coffee houses as market builders, not threatening competitors. Does anyone really think that Wal-Mart really cares about gaps or retail leakages? Wal-Mart is criticized precisely because it is the quintessential retail raptor — it will come in and grab an enormous market share whether or not a gap exists.

A traditional gap analysis can point out opportunities to create new retail niches, but will totally overlook the opportunities to create raptor retail niches out of strong existing downtown niches. For example, my firm DANTH, Inc. recently did an economic development strategy for a very attractive suburban community in NJ. A prior study had noted that in the home furnishings area there was a sales surplus within the township — local merchants had more sales than local residents were spending for home furnishings products. The prior study, producing a typical conclusion for a gap analysis, saw no growth opportunity in home furnishings since there was no gap. DANTH, to the contrary, saw home furnishings as a strong existing niche that could expand its trade area and win a small, but significant share in a far larger market area in which over $260 million is spent annually on household furniture and equipment.

In fact, the ultimate goal behind a niche-based retail revitalization strategy is to create such raptor niches, those that can win market share in larger market areas. Moreover, in our experience, it is far easier to take a fairly strong existing niche and make it grow by expanding into new markets than it is to create a totally new retail niche.

I have done many gap analyses. I am certain that I will do many more of them in the years to come. They can make insightful contributions to a productive research effort on which a sound retail recruitment or retail redevelopment strategy can be based. But, they should not be the sole analytical effort. Downtown managers must also be able to identify, through relevant research, opportunities to attract individual retail raptors and to develop raptor retail niches.

Nail, Hair and Skin Salons: Bane or Boon?

By N. David Milder

DANTH, Inc.

October 15, 2005

Downtowns frequently complain that they are being overrun by nail, hair and skin salons as well as other personal service operations such as fitness centers and spas. For many years I, too, viewed clusters of these personal service operations as indicators of a weak downtown retail base and an eroding environment for pedestrians. Today, I have a much more nuanced view of “salons” and other personal service operations. In some downtowns these operations may pose considerable challenges, but in others they can be real assets worth nurturing. Let’s examine typical fears about these sorts of businesses, and the rationale for a reassessment.

Why salons are often feared as a bane

Opposition to personal service operations, especially salons, can be intense and sometimes provoke local government actions to constrain their growth. For example, elected officials in Nutley, NJ (pop. 27,360), and Maplewood, NJ (pop. 23,870), recently have passed ordinances prohibiting nail salons from being within 500 feet of each other — a zoning tactic used in other communities to disperse porn shops.

Opposition to salons and other personal service operations are frequently based on the fear that they:

- Reduce the number of retail venues and diminish the merchandise selection that the downtown can offer to shoppers. In some districts their growth does force out shops offering comparison shoppers goods, leaving the retailing to convenience operations, which indeed weakens the downtown.

- Inhibit window-shopping and strolling by downtown visitors because their windows lack merchandise and are thus deemed not interesting to look at (more on this later).

- Are willing to pay high rents and thereby make it more expensive for new retailers to enter the district and existing retailers to renew their leases

Why salons should be seen as an asset

While vacationing in Beverly Hills, CA (pop. 33,780), a few years ago, my wife Laura — knowing of my then low-regard for personal service operations — pointed out how many hair, nail and skin salons as well as spas and gyms we had seen as we strolled the downtown area. We did a quick count and stopped at 35. Discussions with relatives and friends who live in California evoked knowing smiles. These establishments, they said, were key elements in the way that Beverly Hills operates. The wealthy like shopping, but love having their bodies pampered. And shopping and pampering often go together. I concluded that if the personal services were such an asset in such a chic district as Beverly Hills, then I should reconsider my attitude towards these operations. Here is what my reassessment brought to light:

The unique strength that downtowns can have is their ability to generate large numbers of multipurpose trips. Financial, insurance and real estate services have long been key assets in many downtowns, be they small or large. But personal service operations, such as the salons of famous hair stylists, skin salons and spas also have long been important attractions in some of the greatest American and European downtowns.

This appears also to be happening in much smaller, less glamorous, and lower profile downtowns as well. For example, an Elizabeth Arden Red Door Spa will be anchoring a major new redevelopment project in Cranford, NJ (pop 22,580). In the Bayonne Town Center, Bayonne, NJ (pop 61,840), a “pamper niche” containing 33 businesses based on gyms, spas, hair salons and nail salons draws lots of people to the Town Center from Bayonne and beyond.

Nationally, the demand for such personal services has seen very strong growth. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, between 1997 and 2002, revenues from hair, nail and skin care services jumped by 42 percent nationwide. Revenues from “other personal services” increased 74 percent over the same time period. Meanwhile, retail revenues have been stagnant at best. Downtown leaders would be crazy to ignore such a growing market opportunity.

Personal service operations usually have much smaller market areas than comparison retailers. The latter can be in another town and still capture the same shoppers, but the salons and spas usually need to be in or near a downtown to tap their customers.

Many downtowns have few income-producing residential units above their retail-prone commercial spaces. In others, such residential units are rent controlled. This means that landlords must rely on their retail spaces to obtain their desired revenues. This creates a pressure for high commercial rents. Quality retailers can easily find competitive locations to suit them and so rarely pay high rents. The personal services have fewer locational options, so they are more likely to pay the higher rents.

A hemorrhage of comparison retailers is a serious problem that requires strong intervention. If this is happening downtown, it’s not because nail salons crowded them out. And while a zoning response may limit or prevent nail salons, it still allows other service operations such as hair salons and real estate offices to open. Often, the underlying problems are more structural and their resolution involves ways of providing more income for landlords, e.g., by removing rent controls or providing incentives to create revenue -generating above the store residential units.

Many districts find themselves with an over supply of retail-prone commercial spaces that is in poor condition and difficult to rent to quality retailers. Much of this poor quality space also cannot be supported by local consumer retail spending power. In such instances, the entry of personal service operations can function to lower the overall vacancy rate and generate foot traffic.

While personal service operations may not offer mer+++chandise in their windows, they often can provide great “informal entertainment” attractions: people in motion behind the windows, getting pampered, working out, kids demonstrating discipline and grace in the martial arts or ballet. These establishments can be real assets as downtowns rely increasingly on entertainment.

Salons and barber shops are often key social institutions, where people gather to socialize and gossip as much as to have their bodies pampered. In many traditional downtown area neighborhoods, the best way to distribute a newsletter or flier is to leave it in the hair salons. Such operations can help a downtown establish itself as the community’s “central social district.”

What to do?

Knee jerk opposition is wrong. Each instance in which personal services exhibit strong growth must be closely examined, as they are often unique. Often, a profusion of salons and other personal services can be a real traffic generator and a strong downtown asset. In other instances, they can be a symptom of tough underlying problems relating to property ownership and retailing. In such cases, it is important to respond to the causal factors and not just their symptoms.

As We Leave the Recession, Affordable Retail Rents Are a Revitalization Imperative

By N. David Milder

DANTH, Inc.

Published in the Downtown Idea Exchange May 2010

Introduction

As we slowly emerge from the Great Recession the time has come for downtown organizations to work hard on encouraging small independent retailers to seek affordable rents and landlords to offer them. If they do not, downtown retail will contract and street level storefronts will be occupied even more by financial and personal service operations – or remain vacant for long periods of time.

In the new normal, small downtown retailers will be facing increased pressures to keep their operations lean and mean because capturing sales from today’s deliberate consumers is far more difficult than from the abnormally free-spending shoppers of the 1990s and 2000s. One budget line item they can focus on is the cost of the spaces they lease for their stores. This is a major long-term business expense and it is important that these retailers do not pay more than they can afford. It is also a business cost where “newbie” retailers dominate those going astray, though badly inept or unscrupulous merchants also tend to pay a lot more than they what good merchants would deem affordable.

Looking at the other side of the coin, it is also in the interest of landlords to ask tenants to pay affordable rents. In the new normal, far fewer stores will be opened by national chains and, among those, a smaller percentage than in the past will be placed in downtowns. Landlords, as a result, will need many local independent retailers to fill their storefronts. This will also be true to a significant degree for those who have built new mixed use buildings with expensively constructed ground floor storefronts. Additionally, as their rents reach ranges considered unaffordable by competent merchants, the more likely they are to attract incompetent or sleazy businesses and also more likely to have storefronts stand vacant for long periods of time.

Defining Affordable Retail Rents

A useful formulation for determining an affordable retail rent is roughly 15% of the shop’s annual sales. DANTH’s merchant surveys and personal interviews with merchants over many, many years as well as the work of other firms, such as Urbanomics, found that downtown merchants generally felt that they could afford total rent costs that were 8% to 12% of their annual sales. However, more recently merchants say they are OK with 15%. While there is certainly some error factor present here, 15% is probably plus or minus just a few percentage points off the correct number. The major points of the analysis presented below are not affected by this error factor.

In a typical downtown, independent retailers with annual sales of $500,000 to $1 million are relatively rare. Most independent downtown retailers would be quite happy with sales in the $300,000 range and joyous with sales around $450,000.

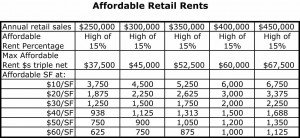

The table above depicts information about:

- How much rent is affordable to retailers with $250,000, $300,000, $350,000, $400,000 and $450,000 in annual sales.

- How many square feet of space this “rent money” can buy at various prices per square foot.

The table also shows how with increased rents more and more of a downtown’s most successful merchants cannot afford to occupy the amount of space they might even minimally need for their operations. Look at how quickly “small” spaces in the 1,500 SF to 2,000 SF range become unaffordable. At $40/SF not even a retailer with sales of $450,000 can afford a 2,000 SF; at $50/SF even a 1,500 SF storefront becomes out of reach. Of course, for the $300,000 shopkeeper, that happened at lower rents: a 1,500 SF shop is unaffordable at rents of $31/SF and 2,000 SF at $22.50.

Affordable rents should be tied in with balloon leases, where rents increase at an agreed upon rate as the retailer’s sales grow. Some savvy downtown landlords are already using balloon leases.

To The Groaners

To the downtown managers and Main Street managers who groan that is impossible to deal with landlords:

- Dealing with downtown landlords and dealing with them effectively is part of your job. If you are not doing it, start doing it. If you do not how, learn how. If after all that you still can’t deal effectively with landlords, get another job.

- Every occupation has jerks; but they also often have a lot of reasonable, effective and even innovative people. This applies to landlords, too.

- Find the landlords you can work with to implement an affordable rents program, then use them as a model to recruit others

- One thing is certain: if you do not try, nothing will happen.

To landlords and developers who groan that they need the high incomes from their new and expensively constructed retail spaces to pay off their loans:

- You are big boys, you like to brag that you are big boys, so act like big boys

- You either goofed in your calculations or you really did not understand that in most downtown mixed use projects outside of places like Manhattan and downtown Chicago, etc., the residential and office rents, probably for some time, will have to subsidize the retail spaces. This is especially true of unproven, revitalizing downtown locations

- Given the current economic conditions your options are really either affordable rents that will diminish your losses or long-term vacancies and continued lack of rental revenues

To landlords who believe they should get market rate rents as defined by the highest asking rents they’ve heard about in the district:

- Your unaffordable rents are likely to produce vacancies, because so few accomplished retailers would be interested, or perpetual churn, because you are likely to attract inept or schlocky merchants who are prone to failing or disappearing

- This will affect the resale value of your property and this is not a great time for any commercial property

- Have you really calculated the difference between the income that an affordable rent will yield and the zero dollars you will likely reap from the months your stores stay vacant because you want higher rents?

The Growing Importance of Downtown Multichannel Retailing

By N. David Milder

DANTH, Inc.

Published in the Downtown Idea Exchange May 2012

The Great Recession, fused with many prior socioeconomic trends has produced a “new normal” for downtowns. Downtown leaders must adjust their thinking about how downtowns function and how they can be revitalized. One critical change is the emergence of multichannel retailing which blends brick and mortar stores, e-commerce, catalog sales, and backdoor retail channels. While the large chains are rapidly adopting this strategy, independent merchants that dominate small and medium-sized downtowns have been slower to adapt. Consequently, many downtown organizations need to create programs that facilitate transitioning independent merchants to multichannel retailing.

The emerging multichannel paradigm

For decades, downtown merchants have had an overwhelming focus on a downtown’s physical stores and the customers that come through their front doors. Today, successful retailers are increasingly pursuing a multichannel strategy in which they integrate their physical stores with a strong Internet presence. The Internet now is involved, one way or another, in 45% of the nations retail sales.

The role of the physical store may be changing, but it will not disappear. Physical stores may no longer be the sole point of sale. Many retail chains are finding that while brick and mortar sales may be stagnant, online store sales provide growth opportunities. Many customers may use the Internet to research merchandise, which they then purchase in a physical store. However, shoppers may also visit physical stores to examine a product, and then buy it online to save on sales tax or for a lower sales price. Either way, single channel stores are likely to be outside of this critical search-purchase behavioral pattern.

Downtown merchants that adopt a multichannel approach may be able to increase their penetration of their current market area while expanding its boundaries. E-retail and backdoor retail channels can lessen dependence on walk-in customer traffic by providing meaningful interactions with consumers in their homes, on their jobs, in their social groupings, and while they are traveling. Getting downtown small business operators on the Internet remains a challenge, but this may be overcome if their downtown organizations properly scope out why they are so Internet resistant and then implement corrective programs.

How downtown organizations can support merchants

With the growth of multichannel retailing, downtown organizations need to ask themselves if current programs and allocations of staff and money are appropriately responsive to the situation.

Backdoor retailing allows merchants to sell to local businesses, organizations, and municipal agents, as well as to consumers at other locales where they can deliver information, show and deliver merchandise, and conduct sales. E-stores, web pages, and the use of Twitter and Facebook are recent electronic variants of backdoor retail operations. There are many nonelectric variants that small businesses uncomfortable with ecommerce may find easier to implement. For example:

- The owner of a gourmet chocolate shop with a website focused not only on individual customers, but on corporate gifts and wedding favors speaks about the health benefits of chocolate at meetings of healthcare-related companies, and has booths at bridal shows.

- A tobacco shop in Rutland, VT, is also a distributor of tobacco products to merchants in Rutland and the surrounding region, with annual sales ranging from $1 million to $2.5 million.

- A women’s clothing shop takes its wares to model and sell at local women’s clubs, PTA meetings, etc.