Posted by N. David Milder

Why Restaurants Can Be So Important for Downtowns

1. They Can Strongly Respond to Very Basic Human Needs. At the most fundamental level, downtown restaurants can be powerful because they can help fill many of the most basic needs of downtown users. Most obvious is the need for food when people are away from home. Those likely to have such a need include downtown visitors from near and far, those who work in the downtown as well as residents in or near the downtown who want food other than what their pantries and refrigerators can provide. Additionally, to basic sustenance, the food’s quality can provide pleasure or pain, delivering strong incentives for return visits or avoidance.

The context in which the food is provided also can satisfy our basic needs for social interaction and our desires to be with people who we like and enjoy. Responding to these needs, many cultures highly value providing bounteous good food and drink at a meal shared with others as an essential way of displaying hospitality, affection and respect to others. We often go to restaurants to have a good time and that usually means not only enjoying food and drink, but also sharing those pleasures with those we like or love.

Really great restaurant operators understand the drawing power that can be created by an eatery that responds across the board to our needs for sustenance, pleasure and social interaction — and they include themselves in the equation. For example, Jean-Claude Vrinat — under whose leadership Taillevent dominated the Parisian restaurant scene for decades — once explained that great food, great wines and great service were necessary, but insufficient reasons for his restaurant’s success. The key factor was to treat all of his guests as if they were members of his family. His quests, he believed, were looking, most of all, for an enjoyable, entertaining experience and this had a very important social component that his restaurant had to respond to. Of course, his food and wines had to be exceptional (his wine cellar was legendary), but it was the ability to make his guests feel at home while having an exceptional experience that made Taillevent truly extraordinary.

Restaurants also provide pleasure through their ability to function as informal entertainment venues. People watching is perhaps the simplest form of entertainment and restaurants can provide copious opportunities for watching the ways that fellow diners and restaurant staff behave. Many of the staff’s activities are like well-practiced performances: flambéing food, the opening of wine bottles, filleting fish, mixing drinks, the making of pizzas and tandoori foods, etc. Indeed, some restaurants even have chefs tables where guests pay extra to be able to watch their food being made.

Few, if any, of the other types of downtown operations can respond to a similar package of basic human needs. Restaurant operators who understand that they are selling a lot more than just the calories needed to keep their customers’ bodies functional are much more likely to be successful.

2. They Can Perform Critical Social and Economic Roles. Restaurants are sometimes special neighborhood meeting places where people who live or work in an area go to be with their neighbors, coworkers and friends. British pubs, the “locals,” are great examples of this, but their functional equivalents can be found around the world and in places large and small in the USA. They can provide the “third places” that help generate a sense of community in a district and structure its cohesion.

Popular eateries and watering holes within easy reach also can be a critical amenity for firms in many downtown niches. Hotels, antiques shops, museums, and theaters, for example, typically draw their patrons from a much larger trade area than their downtown’s retailers and these patrons have a high probability of needing food and comfort during their visits.

Downtown retailers also may find that nearby eating and drinking places are pleasing and needed amenities for their customers. Often, a strong downtown restaurant, e.g., the Golden Lamb in Lebanon, OH, or a restaurant niche, e.g., in downtown Rutland, VT or Morristown, NJ, , can bring in customer traffic that can be shared with downtown retailers. In 2010, in downtown Morristown (town population 18,529), there were 77 restaurants and nine cafes/coffee bars and this niche drew more customers downtown than any other economic segment in the district. A ballpark estimate of this niche’s sales was $79.4 million+. The fact that 21 downtown eateries were listed in Zagat is very unusual for a downtown of this size. The 11 rated in Zagat averaged 20+ scores on food, service and décor, indicating that they were well-regarded by their customers (1).

However, in many small and medium-sized districts, a lot depends on how the operating hours of retailers and restaurants overlap. For example, retailers who close at 5:00 pm or 6:00 pm are not likely to benefit much from a popular nearby restaurant that is only open for dinner. Similarly, a shop that opens at 10:00 am is unlikely to benefit much from the customer traffic generated by a nearby eatery for breakfast.

Eating and drinking places also can have some impact on the locational decisions of both residents and businesses, though it is probably not decisive. Their influence on corporate locational decisions has likely waned over the past 30 years. Back in early 1984, Regional Plan Association surveyed 47 major corporations headquartered in Manhattan about the criteria they used to assess potential back office locations. Fifty-one percent reported that the proximity of restaurants and shops were important (2). It was the sixth strongest of the 19 locational criteria the corporations were asked about. Today, it is doubtful that a similar survey would have comparable results. Large corporations now want to keep their staffs inside their buildings as much as possible. To that end, many have on-site subsidized cafeterias, with some (e.g., Google) famously even providing free food. However, it can be reasonably argued that popular eating and drinking places may be a more important locational factor for downtowns that have a lot of smaller businesses with workers that need to do a lot of social networking, e.g., where there is an innovation district or in county seat downtowns.

According to a 2013 survey done for the National Association of Realtors, about 45% of Americans want to live in a city or suburban area that is near shops, including restaurants (3). The survey also found that 42% of the respondents felt there were too few shops or restaurants within an easy walk of their homes, while 48% felt there was the right amount (4).

Very importantly, restaurants are also often pioneers in revitalizing neighborhoods and commercial centers. Three powerful reasons for this, as will be discussed below, are that:

- The much venerated real estate adage “location, location, location” seems to hold less power for restaurants than for other commercial operations

- Restaurant often need to capture a much lower market share to survive than other commercial operations

- Affordable rents, e.g., less than 10% of annual sales, are critical to a restaurant’s success and often are more easily found in areas that may be distressed, but have “good bones” and an attractive location.

Some Important Factors That Impact on the Success of a Downtown Restaurant Niche

1. Density of Potential Customer Spending Power. When it comes to restaurants and dining out, trade area population size and household incomes are two very important factors. Together, they determine the size of the pool of dollars for which restaurants can compete.

Residential Populations. Obviously, larger towns have more people, who are likely to have, in aggregate, more money to spend in restaurants than the residents in smaller towns. Consequently, the larger towns are likely to have more and stronger restaurants in operation.

For the analytical needs of most communities in the US, the densities in our very largest cities are so great that they stand apart and their restaurant scenes are not salient. For example, in 2007, New York City had 16,921 eating and drinking establishments that captured about $14.4 billion in annual sales (5). Looking within the city, in a 3-mile radius of the Queens Plaza commercial district in the Borough of Queens, there are about 1.18 million residents who spend about $2,9 billion annually on food away from home (6).

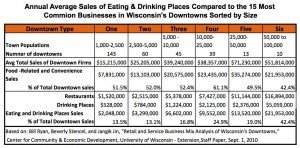

The table above, based on some excellent research by a Bill Ryan led research team, is more reflective of what will be found in most states. It shows some interesting business sales data for downtowns in 303 communities in Wisconsin with populations ranging from 1,000 to 100,000. It presents the average total annual sales of eating and drinking places in these downtowns and enables them to be compared to the total annual sales of the 15 most common types of business found in these downtowns, with the results sorted into six categories according to the towns’ population sizes. Some findings to consider:

- The average total sales in these 300+ downtowns does not rise strictly with the size of their community’s population. Sales peak in the communities with populations between 25,000 and 50,000. This indicates that other explanatory factors are involved. Household incomes is certainly one of them. The size and nature of the downtown’s close-in residential population is probably another

- Food-related and convenience sales, which includes both restaurant and food store sales, represents at least half of the total downtown sales in all the communities with less than 50,000 populations. Interestingly, they represents just 42% of the downtown sales among those in the 50,000 to 100,000 range. There are no food store sales reported in the 10 downtowns in that category, just sales from eating and drinking places! The lack of food store sales supports the hypothesis that the downtown’s close-in population is an important explanatory variable

- The total sales of the eating and drinking establishments increases steadily with population size from about $2 million in the communities with 1,000 to 2,500 populations to $22,9 million in cities with population between 50,000 to 100,000

- The sales of the eating and drinking places in smaller communities, with populations under 25,000, range from about $2 million to about $9.5 million. While $2 million is the lowest amount of sales, it is not a negligible finding. First of all, it shows the capability of these eating and drinking places to capture real dollars. Two million dollars are not chump change. Also, in these smaller towns, most of these establishments do not have to be $1 million or even $500,000 operations to survive or perhaps prosper

- Looking across the six population categories, there is an unsteady trend for the percentage of total downtown sales captured by eating and drinking places also to increase, with a very slight decline in category “Two” and more substantial decline in category “Five. The latter is not unexpected, since the total sales variable is in the equation .

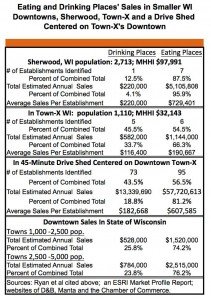

To get some tangible idea of what such sales might mean in smaller communities, let us consider two small communities in WI, Sherwood and Town-X. The table immediately below presents some data on their restaurant scenes.

The data demonstrate that despite their size, small towns still can attract quite a few eating and drinking establishments. Sherwood, WI, with a population of 2,713, has one drinking place and seven eating places. (Several of the eating places also have strong bars.) Town-X, WI, with a smaller population of 1,110, has five drinking places and six eating places. Having a lot of drinking establishments appears to be common in the part of WI where Town-X is located: about 45.5% of the eating and drinking places in Town-X are watering holes, while that percentage for a surrounding 45-minute drive shed is 43.5%. An important difference is that the average sales of Town-X’s eating and drinking places are significantly smaller than comparable establishments in the drive shed. Two possible explanatory factors are that parts of the drive shed are more densely populated than Town-X and the town’s median household income is about 14% lower than the shed’s. Nationally, many other small towns will have eating and drinking places with characteristics similar to those found in Town-X: they are relatively numerous, with relatively low sales and a comparatively high percentage of drinking establishments.

From a downtown revitalization perspective, the problem with the restaurants in such smaller communities is often more their quality than their potential to be profitable (which certainly is challenging for all restaurants). In turn, this is influenced by the difficulty in attracting more capable operators, who are likely to find the larger profit potentials of bigger communities more attractive. While many smaller town restaurant operators have the ability to become more accomplished through training, the bottom line question is: do they have the motivation, time and money to get such training?

Featuring quality local food products and dishes is certainly a sound business strategy, but if having a local focus means operators are responding to undemanding standards for food, service and ambience, be they their own or those of their local customers, they are unlikely to grow their trade areas or attract many tourists.

Sherwood demonstrates another pattern, that is rarer, but happens often enough to deserve notice. Sherwood is located on the fringe of the Appleton Metropolitan Area, near a popular state park that sits on Lake Winnebago. Its residents have a median household income of almost $98,000/yr. Its restaurants have total annual sales, about $5.1 million, far above the $2.5 million average for towns in the 2,500 to 5,000 population range found by the Ryan team. DANTH’s research found Sherwood restaurant owners reporting that most of their customers were from other communities, yet there was still sufficient leakage of local residential restaurant expenditures to warrant recruiting some new operators (7). Apparently, the Sherwood restaurants’ concepts were more suited to out-of-towners than local residents, so the residents went elsewhere. This is not an uncommon situation in communities benefiting from a strong tourist trade or that are comparatively affluent and their eating and drinking places attract less affluent diners from nearby communities.

Other Downtown Users. Downtown office, blue collar and uniformed workers, tourists and students are other important components of a downtown’s daytime population that heavily structure the demand for downtown food services. A good example of this is Gering, NE, the county seat of Scotts Bluff County. It has a residential population of 8,480. Its downtown daytime population has the following components:

- About 1,544 people employed within a 10- minute walk of the downtown’s center. About 1,127 were probably office workers who had an estimated annual expenditure potential of about $1.5 million for food services

- There are about 3,951 people employed within a 5-minute drive of the downtown’s center, of which about 1,954 are probably office workers. They had estimated expenditure potentials of $2.6 million for food services

- The grade school, junior high and high school within reasonable walking distance of the downtown have a total of 1,261 students. The 640 high school students have a direct spending potential of about $0.9 million, a significant percentage of which is for food services

- Gering has three significant tourist market segments. About 122,000 people visited the nearby Scotts Bluff National Monument in 2012, most passing through the downtown. Roughly 50,000 people attended events at the Gering Civic Center annually. Gering’s hotels had about 29,000 guest nights in 2012. These three tourist market segments annually bring into the county about $4.2 million in purchases from food service operations (8).

A diverse set of downtown of users is possible in towns large and small. These user segments are likely to frequent restaurants at different times of the day: e..g., seniors at mid-morning; office workers at noon; students after school and residents in the evening.

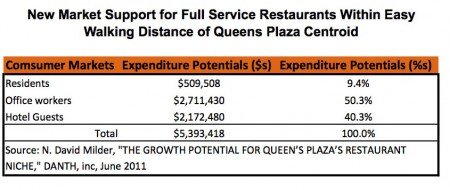

The strength of these user segments and their impacts on downtown eateries can have considerable variation. For example, in some of our larger cities, the residential market may be significant, but not nearly as strong as the daytime workforce or downtown hotel guests. This is the case in the Queens Plaza commercial district. It is located in NYC’s Long Island City neighborhood that has seen considerable economic growth over the past decade, even through the Great Recession. In this district, new restaurants will appear in response to the new residents, office workers and hotel guests that have come into the area. As can be seen in the above table, residents represent only about 9.4% of the new restaurant demand, while the office workers and hotel guests account for much higher shares, 50.3% and 40.3% respectively. In a significant number of smaller downtowns, e.g., Gering NE, the downtown workers and tourists also can be critically important to restaurants because they constitute such a high proportion of their daytime users.

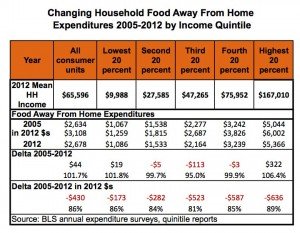

2. Household Income Strongly Influences Food Away From Home Expenditures. Restaurant demand in a trade area is impacted not only by population density, but also by the household incomes of those who live, work and visit the area. Surveys by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) have consistently found that, unsurprisingly, food away from home expenditures rise with household incomes. As can be seen in the table below households in the highest income quintile (e.g., highest 20%) spent on average $5,366 dollars in 2012 in eating and drinking places, while those in the middle quintile spent $2,164 and those in the lowest spent just $1,086.

Also, the BLS consistently has found that the households on the highest rungs of the income ladder account for a very disproportionate share of the food away from home expenditures. As can be seen in the table above, the 20% of the households with the highest income in 2012 had an average income of $167,010 and accounted for 40.2% of the nation’s food away from home expenditures. Combined with the next highest income quintile (the fourth 20 percent in the table), they they represent 40% of the households, but close to two-thirds of all food away from home expenditures.

The ability of a downtown to attract and support eateries and watering holes will be strongly impacted by how household incomes are distributed in its trade areas. Most downtown trade areas will be dominated, in varying degrees, by households in the three national middle income quintiles. Placing the median household income in your downtown’s trade area in its national income quintile can:

- Provide a quick and easy indication of the strength of your local restaurant demand

- Help calibrate local expectations about the type of restaurant niche the downtown can reasonably be expected to support

The Decline of Middle Income Households. While, over the past decade, our largest cities have seen strong growth in the number of relatively affluent people who live in or within easy walking distance of their downtowns, most of the other communities in the nation still have downtowns that are dependent on middle income customers. The problem they face is that the number of middle income households — broadly defined as those with incomes between $35,000 and $100,000 — has been decreasing (see the chart below).

Another problem is that the incomes of middle income households have been stagnant for many years, even well before the Great Recession. For example, in 2013 dollars, the median household income nationally was $56,800 in 2000, $56,436 in 2007 and $51,939 in 2013 (9).

The reduced number of middle income households and their stagnant incomes have posed demand constraints on restaurants in most of our nation’s downtowns and there are few indications that they will soon or easily go away.

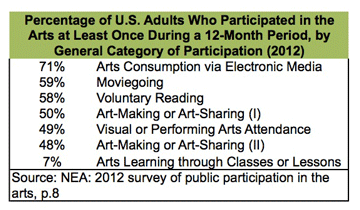

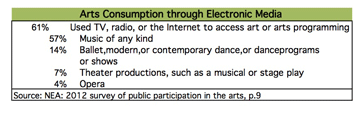

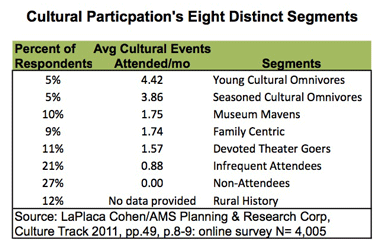

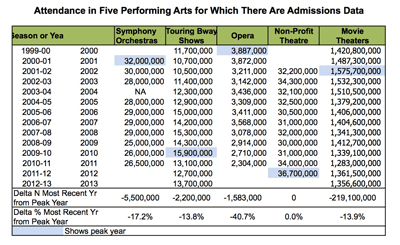

3. Lifestyle Segments and Age Cohorts Impact Restaurant Preferences and Behaviors. People live different lifestyles that entail different sets of consumer preferences and behaviors. This means that even among people with similar incomes, their different lifestyle preferences will lead them to patronize different restaurants and to vary in how often they go out to eat. The table below shows how often three lifestyle segments are likely to visit 19 restaurant chains compared to the national average

that is expressed in the MPI Score. These data are from ESRI’s Tapestry dataset and cover the market areas of the Queens Plaza commercial district in NYC. There are other vendors of such data and they are available for almost every downtown trade area.

Baby boomers and millennials are the two largest age groups and they each have an enormous impact on ur economy and restaurant industry. The baby boomers are now in or soon entering the retirement portion of their lives. The millennials, aged from 18 to 30 or 35 are the ones that will have increasing impact as they age, nest and make more money. Our pre-Internet retail and restaurant industries were hugely influenced by the baby boomers; today they are increasingly impacted by the 50 million to 60 million millennials. However, more restaurant expenditure dollars now are in the pockets of the boomers than in those of the millennials. The millennials are in the start up phase of the their careers and the Great Recession heightened their unemployment numbers. They also have been much slower than the boomers to marry and buy homes and cars.

Nonetheless, evidence suggests that the millennials are disrupting the restaurant industry. As one observer noted:”millennials tend to spend their dining dollars sparingly and in a more calculated way” (10). They eat out less often than the baby boomers did at a similar age. Between 2009 and 2013, their restaurant visits dropped by 16%. While they still go to traditional fast-food hamburger chains like McDonalds and Wendy’s, they prefer the newer chains such as Shake Shake, In-N-Out Burger and Smashburger. “Fast casual” chains, such as Chipotle and Panera Bread, are also very popular among millennials (11 ).

While the impact of the millennials will only increase as they age and accrue greater wealth, for many downtowns the boomers probably represent a stronger market segment on which to build their restaurant niches. For example, in rural communities, small towns and rust belt cities, many of their millennials are fleeing to larger, more successful cities that have more and better jobs as well as hip downtowns and neighborhoods.

Hipster creatives who live in our large successful cities (think of Austin, Charlotte, Atlanta, DC, NYC, Boston) are a subset of the millennials. They probably have a lower unemployment rate and higher incomes than other millennials and may well have less depressed restaurant visitation rates and expenditure levels.

4. The Rise of the Deliberate Consumer. The Great Recession, much like the Great Depression, brought about important changes in consumer behavior and expenditure patterns. In turn, these consumer behaviors induced most retail chains to rethink how many stores they needed and how large these stores should be. The most important change in consumer behavior is the emergence of the deliberate consumer, whose key characteristics are well summarized by the findings of survey of 8,000 Americans completed in January 2010:

- “51% (of respondents said) they have become more budget conscious and will consider each purchase more carefully over the next five years.”

- “60% (of respondents said) they now focus on what they NEED versus what they WANT” (12).

While deliberate consumer behaviors were less prevalent in affluent households, whose numbers diminished as the values of the investment portfolios have returned to or exceeded their pre-recession levels, middle income households still strongly act like deliberate consumers. One area where these deliberate consumer behaviors have played out is food away from home expenditures.

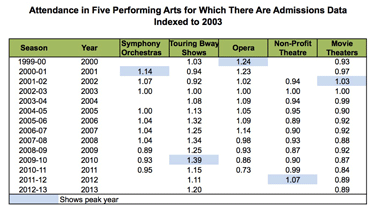

5. Declining Food Away From Home Expenditures, Especially in Middle Income Households. Supply side data from the Census Bureau on the total sales and per capita sales of food services and drinking places between 2002 and 2012, as shown in the table below, appear to indicate that, with the exception of 2009, sales in this industry have had a steady path of growth.

The Great Recession appears to have had just a brief and mildly negative impact.

However, demand side data from the BLS, based on large annual, rigorously done surveys, tell quite a different story. The table immediately above shows a comparison of food away from home expenditures for 2005 and 2012 broken down by household income quintiles in two ways, with one converting the 2005 expenditures into 2012 dollars. The analysis using unconverted 2005 dollars shows:

- A slight percentage growth for all household units of 1.7%

- A slight increase for the lowest quintile of 1.8%

- Decreases in the middle quintiles, with those in the second and fourth being slight, but the third quintile had a decrease of 5%

- The top income quintiles expenditures increased by 6.4%.

The analysis using 2012 dollars for both years paints a much more worrisome picture. Between 2005 and 20012 the value of food away from home household expenditures:

- Fell by about 14% for all household units

- They fell by 11% or more across all the quintiles

- They fell the most in the middle three quintiles: 19% in the third, 16% in the second and 15% in the fourth

- Even expenditures in the wealthiest quintile fell by 11%.

The BLS data show that the middle income households that most American downtowns and their eating places depend on have significantly reduced their food away from home expenditures.

6. Churn, Upheavals and Closings Among the Restaurant Chains. As of this writing, McDonald’s has just changed its CEO in another attempt to re-ignite sales growth in the USA, where sales of been stagnant in recent years. The mighty McD is worried about its product mix, franchisee disenchantment and increased competition from the growing fast casual chains. But, McD is not alone in trying to rejuvenate their food and operations. Burger King seems to be in a perpetual redo and/or change of ownership. Big Boy and Blimpie closed.

Family eateries also have been feeling a strong pinch. This is understandable since their customer bases were often the middle income households that have reduced their restaurant expenditures. The Darden chain, for example, has redone or sold Olive Garden and RedLobster. Bennigan’s, Tony Roma, Ground Round, Country Kitchen and Ponderosa have closed.

On the other hand new chains have emerged and grown such as Panera Bread, Chipotle, Shake Shake, Five Guys, In-N-Out Burger, Smashburger, etc.

The tumult among the large restaurant chains reflects forces that are very likely also impacting smaller independent restaurant operators. A search effort found no studies or commentaries on this impact. However, it seems reasonable to suggest that today’s independent operators are facing far more uncertainty than they would have a decade ago.

Some Important Factors That Impact on the Success of Downtown Independent Restaurant Operators

In a very important 2005 article, Parsa, Self, Njite, and King (PSNK) argue that internal factors –e.g., how the restaurant is operated, the operator’s management skill set and ability to maintain family cohesion, the restaurant’s concept — have more impact on a restaurant’s viability than external factors — e.g., competition, location, customer attributes — though the latter are still important (13). This emphasis on the operator resonated with the findings from DANTH’s interviews over the years with restauranteurs and the salespeople who sell them liquors and wines. DANTH was told repeatedly that it is very hard for a restaurant to succeed and, most importantly, that the operator has to know what he/she is doing, preferably based on significant experience in the industry.

1. Restaurant Competition/Density Within the Trade Area. PSNK acknowledge that “a restaurant can benefit from close proximity to competition and restaurants are often located in clusters to attract more traffic,” but their data analysis found that restaurant failures were highest in zip code areas having the highest restaurant density. They suggest that:

- Restaurants need to have clear and effective concepts that differentiate them from their nearby competitors

- A careful eye needs to be kept on the market area to see if it has become saturated.

DANTH’s research has not found any easy indicator of when a restaurant niche has topped out. The number of restaurants, which is frequently cited by unhappy downtown business operators as an indicator of saturation, is not reliable. For example, the Little India cluster/niche on 6th Street in Lower Manhattan topped out with about 35 restaurants, but the 70+ eateries in downtown Morristown (a much less densely populated community) are still growing.

PSNK’s point is important: restaurant niches can top out at some point because of saturation and it is very important to know when it is about to occur.

A Positive Market Entry Factor In Smaller Communities. In smaller, less densely populated communities, it may be easier for restaurants to enter the market than is the case for other types of businesses. As can be seen in the table below, they usually do not need to capture as high a share of the trade area’s consumer expenditures in order to survive as do retail and most personal service operations. This means that restaurant operators, in these communities, need to attain a lower lever of competitive success for their businesses to be viable; they do not need to be as capable as the operators of the other types of businesses.

Location. According to PSNK, where a restaurant is located can influence whether it will succeed or fail. Things like pedestrian and auto traffic, visibility, strong nearby merchants and institutions count. However, very importantly, their research found that while a poor location can hurt, it can be overcome by a great product and operation. On the other hand, PSNK argue, a good location cannot overcome a bad product or operation. This is an extremely important finding for revitalizing downtowns!

Rents. One of the reasons that savvy restauranteurs often select locations that, according to conventional wisdom, are not choice, is that they offer very reasonable and affordable rents. Many restaurant operators have told DANTH that affordable rents are a key variable in where the locate new eateries and whether they will renew leases. Rents are often cited as the reasons why popular restaurants have either moved or closed — even those that are famous. Here in NYC, for example, Bobby Flay recently closed Mesa Grill and Danny Meyer will soon close his Union Square cafe because of substantially increased rents.

Restauranteurs usually can afford to spend about 10% of their annual sales revenues on rent. That means that for every additional dollar spent on rent the restaurant needs to get 10 in sales to afford the increase.

This influences where they are likely to locate. Generally, in big cities, they avoid downtown streets with the highest commercial rents, though they may be on nearby side streets.

Revitalizing downtowns in cities with significant populations sometimes have their commercial rents rise rapidly beyond what start up restaurants can afford or they still lack the customer traffic the restaurant chains feel the downtown should generate for those rents.

In contrast, smaller towns often have small, non-vanilla box commercial spaces with low asking rents that can be used by a start up eatery. This is another factor that eases market entry and allows low volume eateries to survive.

Restaurant Failure Rates. Regarding failure rates, PSNK found that:

- Contrary to the 90% figure often cited (e.g., by American Express), only 26% of the first year restaurants failed, with the number rising to 60% after three years. After that, longevity became a strong predictor that a restaurant would stay in business. Restaurants do have a bigger failure rate than other types of start ups. For example, one broader study found that:”that new establishments with 500 or fewer employees show an average survival rate of 39.8 percent after six years” (14).

- Small independents had higher failure rates than large franchised restaurants. So while in many communities, it may be easy for them to start up, it also is easy for them to fail.

- Failure also varied considerably by restaurant industry segment: e.g., the three highest three-year turnover rates were Mexican restaurants 86%, subs and bakeries 76% and Coffee and snacks 70%; the lowest rates were seafood 33%, burgers 33% and Italian 25%. That makes one wonder if there is a connection between survival rates and capital investment rates.

8. Entrepreneurial Factors – what helps a small independent restaurant succeed? PSNK mention a slew of factors that impact on restaurant entrepreneurial performance. Below are the ones that came across as being the most important.

Implementing a Well-Defined Concept. PSNK found that one of the most important things that can make a restaurant successful is the owner having a concept for the operation that goes well beyond food production. An effective concept is clear, comprehensive and easy to understand and it actually drives activities in the kitchen, business operations and employee and customer relations. Complicated concepts that use too many tools to reach too many customers are apt to fail. Successful restaurants often are good at just adapting and changing as they confront new challenges and opportunities — without the assistance of any complicated strategic plan.

The Operator’s Family is Onboard. Restaurant operators have long and irregular hours. They also often need family members to take on positions within the company — e.g., hostess, bookkeeper, etc. — or to invest capital in it. A frequent result is that the operator’s family is stressed. Successful owners typically have the support of their families and are accomplished at balancing their home and restaurant lives. Operators often decide to grow, change or leave the business in order to keep their families whole and happy.

PSNK argue that these “quality of life issues” have greater impact on a restaurant’s survival than previously noted by researchers. Many restaurants are closed because their owners are no longer willing stress their families or work long irregular hours.

The Operator Needs the Appropriate Skill Set , Motivation and Experience. Last, but far from least in importance, it is critical for the owner-manager to have the specific skills that are needed to run a restaurant. These are usually acquired or perfected through prior work experiences in restaurants. As is the case for all small firms, the owner is often performs the roles of the CEO, COO, CIO, bookkeeper, advertising manager, human resources manager, purchasing agent, etc. The operator’s drive, determination and passion can also be critical for a restaurant’s success.

Incompetent and inexperienced operators have been frequently cited by scholars to be a primary factor for explaining small-business failures generally. This is certainly the case in the restaurant industry.

Some Take Aways

- Restaurants can have great impacts and make strong contributions to a downtown’s success

- As the performance of central social district functions and the growth of entertainment niches become more important in downtowns of all sizes, so does the importance of its restaurants

- Restaurants can be critical assets and amenities for other downtown niches

- Restaurants can have these important impacts even in smaller communities

- The decline in the number of middle income households and the stagnation in their income growth have placed serious constraints on the growth potential for restaurants in most downtowns

- Even in small downtowns,diverse sets of visitors impact on restaurant demand, both in terms of the expenditure potentials and the types of eating places customers like

- While restaurants can definitely benefit from geographic clustering, too much density within a trade area can stimulate failures. Within a cluster it’s essential for a restaurant to differentiate itself from its close by competitors. It’s also important to recognize when a restaurant niche has topped out, i.e., when the market area has become saturated

- In smaller communities, restaurants often need to capture a smaller market share than other types of retail and personal service operation, which makes their market entry comparatively easier

- While a poor location can hurt a restaurant, it can be overcome by a great product and operation. On the other hand, a good location cannot overcome a bad product or operation

- Restauranteurs usually can afford to spend about 10% of their annual sales revenues on rent. That means that for every additional dollar spent on rent the restaurant needs to get 10 in sales to afford the increase.

- Only 26% of the first year restaurants fail, with the number rising to 60% after three years.Small independents had higher failure rates than large franchised restaurants.Significantly, failure also varied considerably by restaurant industry segment: e.g., the three highest three-year turnover rates were Mexican restaurants 86%, subs and bakeries 76% and Coffee and snacks 70%; the lowest rates were seafood 33%, burgers 33% and Italian 25%.

- Entrepreneurial Factors – what helps a small independent restaurant succeed:

- Implementing a well-defined concept

- The operator’s family is onboard

- The operator needs the appropriate skill set, motivation and experience.

Endnotes

1. N. David Milder, “Downtown Morristown: A Retail Revitalization Strategy And Action Plan,” DANTH, Inc., September 2010, p.23

2. Armstrong, Regina B., and N. David Milder. “Employment in the Manhattan CBD and Back-Office Locational Decisions.” City Almanac 18.1/2 (1984): 4-18.

3. Myers Research and Strategic Services, “NATIONAL COMMUNITY PREFERENCE FREQUENCIES, September 18-24, 212,” p.3. This reports the responses to a national survey with 1,500 respondents that was done for the National Association of Realtors

4 Ibid., p.2.

5. Census Bureau, 2007 Economic Census.

6. N. David Milder, “REPORT on: THE GROWTH POTENTIAL for QUEEN’S PLAZA’S RESTAURANT NICHE,” June 8, 2011, DANTH, Inc. p.3

7. DANTH, Inc. and Short Elliott Hendrickson Inc. “Village of Sherwood: Downtown Market Analysis and Strategy,” August 2012.

8. DANTH, Inc. and Short Elliott Hendrickson Inc. “City of Gering Downtown Revitalization Plan,” February 2014, p.15.

9. Data from the website of the Economic Policy Institute: http://www.stateofworkingamerica.org/charts/real-median-household-income/

10. Stephanie Strom, “Restaurant Chains Try to Woo a Younger Generation,” New York Times, June 7, 2013 www.nytimes.com/2013/06/08/business/as-eating-patterns-shift-restaurant-chains-aim-at-younger-generation.html?pagewanted=print 1/5

11. Ibid.,

12. Cited in: White Hutchinson Leisure & Learning Group White Paper, “The Great Recession: Its Long-Term Impact on Consumers and Location-based Businesses,” February 2010:https://www.whitehutchinson.com/leisure/articles/groundedconsumer.shtml

13. H. G. Parsa, John T. Self, David Njite, and Tiffany King, “Why Restaurants Fail,” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, August 2005, pp. 304-322, p.

14. Phillips, Bruce D and Kirchhoff, Bruce A., Formation, Growth and Survival; Small Firm Dynamics in the U.S. Economy (1989). Small Business Economics, Vol. 1, Issue 1, p. 65-74 1989. Available at SSRN:http://ssrn.com/abstract=1504489

© Unauthorized use is prohibited. Excerpts may be used, but only if expressed permission has been obtained from DANTH, Inc.