By N. David Milder

Revised April 26, 2014

Introduction

On our downtown revitalization assignments over the years, DANTH has heard many local leaders suggest as a major strategic element either creating a formal entertainment venue or improving an existing one. In many instances, this concern was focused on the issue of maintaining or attracting a movie theater, but in many others, the issue was either the saving and renovation of an old theater or the creation of a performing arts center. Additionally, I have either lived in or frequently visited a number of cities where such issues have arisen. Consequently, I used these communities as an informal sample to investigate how their formal entertainment venues operate. Some of the communities included in this sample were: New York City and White Plains in NY; Newark, Rahway, Englewood and South Orange in NJ; Cleveland and Columbus in OH; Carlisle, PA, and Rutland, VT. Admittedly, this sample is both small and not systematic, but I think the observations presented below still are pretty much on target.

Advocates of these formal entertainment venues often advance a two-pronged argument for them that is well articulated by Cleveland’s PlayhouseSquare on its website:

- “As the country’s largest performing arts center outside of New York (it has eight venues), the not-for-profit performing arts center utilizes the arts to engage individuals and attract over one million guests per year to its 1,000+ annual events. These audiences act as the catalyst for economic growth and vitality within the region….

- Stage activity on our multiple performance spaces draws over one million people annually to downtown…people who also dine, shop, work, vacation and help neighborhood businesses thrive.” (Italics added.)

In other words, the audiences of these formal entertainment venues are supposed to have positive impacts on the city or regional economy while generating a lot of new pedestrian and customer traffic for nearby businesses, especially for nearby restaurants and retailers.

In too many instances recently, such advocates also see these formal entertainment venues as providing the missing revitalization engine, the silver bullet solution for their downtown’s renewal. Such advocacy, for example, is frequently to be found voiced in many downtown revitalization related LinkedIn group discussions.

When are these entertainment venues open and why is that an important question?

We visited the websites of the venues in our sample to count how often and when they were open. The vast majority:

- Had an event (sometimes two) on between 80 and 150 days per year; though some venues were as low as four events a month. Most days and evenings of the year they are “dark”

- Most entertainment events occur on weekends; most dark days are midweek

- Daytime midweek events tend to be “educational,” with a lot of school kids being bused in and out

- Most entertainment events are scheduled for the evenings

- A vast majority of these venues are “dead” for three months during the summer, with very few if any events during this time period.

First, it should be noted that most of the venues we looked at do not attract anywhere near the one million visitors a year claimed by Playhouse Square. More typical for smaller communities with populations of less than 25,000 is Theater X, that has 838 seats and in a recent year had 140 events. That translates into a maximum attendance of 117,320, assuming every seat at every event being filled.

More importantly, the audience traffic these venues attract will be arriving at a time of day when most businesses – especially in small and medium sized downtowns — are either closed or getting ready to close. Restaurants and watering holes are the businesses most likely to benefit from this audience traffic. The size of this impact will obviously be related to the size and spending power of the audience flow and the number of events held at the formal entertainment venue.

But, the need for pre-theater meals tends to abbreviate the time available for pre-theater shopping, especially on workweek evenings, even in those shops – most likely chain stores – that are open that late. The truth of the matter is that during most weekdays these venues are generating little or no pedestrian traffic that nearby retail businesses are likely to tap. The same is the case for most evenings and both daytimes and evenings during three summer months.

This, in turn, strongly suggests that the direct positive economic impacts of the formal entertainment venue audiences often are appreciably over-estimated, even the more probable impacts on restaurant revenues. For example, Theatre X claims that it generates about $4 million a year in revenues for nearby downtown eateries and watering holes. That would mean that every one of its maximum 117,320 person audience would: 1) eat a pre-theater dinner downtown and 2) spend $34.09 per dinner. It also means that its downtown eateries can handle a pre-theater dinner rush of 800+patrons. It is very doubtful that every theater patron would have either a pre or post theater dinner downtown or spend on average about $68 for a dinner for two. Also, I seriously doubt that this downtown’s eateries can handle a pre-theater dinner rush of that size in that price range.

Programming: culture, popular entertainment, education

The term “performing arts center” may conjure up expectations of programs filled with high brow cultural events such as classical music, ballets, operas, classic and Broadway plays, jazz, etc. Such performances (including Metropolitan Opera HD broadcasts) are indeed to be found on the calendars of the arts venues we looked at. However, it is interesting to note that PlayhouseSquare says on its website that entertainment is its core and that most of the performing arts venues in our sample have programming that is focused on a broad range of popular entertainments such as:

- Concerts by acts featuring various types of music: popular, rock and roll, folk, ethnic, etc.

- Family shows

- Speakers

- Comedians

- Screenings of the broadcasts of NFL playoff games

- Educational programs and plays for children

- Motion pictures: some show classics on a limited basis; others show new films in cinemas built into their building or on their campus.

Obviously, these organizations are doing what they feel they need to do to drive patrons through their doors and win the earned revenues that will help them stay in business. For example, Eric Mallette, the programming director of Rutland’s Paramount Theater, says “that he pays a lot of attention to what the local market responds to and tries to book shows and adjust ticket costs to fit those trends” (1). For many years that meant popular music and family entertainment, including the booking of a lot of comedians. According to Bruce Bouchard, who runs the Paramount Theater: “We started booking comedians and it just took off” (2).

The importance of making ends meet is demonstrated by the fact that many of these venues rent out their spaces for business meetings, weddings, bar mitzvahs, etc.

It seems to me that, save for one or two exceptions, entertainment center is a far better descriptor of these venues than performing arts center. This is not pilpul, since the distinction can lead to differing expectations for a formal entertainment venue, how it is designed and the operational decisions its management makes.

Some of these venues provide homes for resident performing arts companies — orchestras, dance companies, theatre companies, performing arts schools, etc. This will influence a venue’s programing and the paths and strengths of its economic impacts. It is one of the things, in my opinion, that differentiates a performing arts center from a theatre or a group of theatres.

Have successful formal entertainment venues directly generated more pedestrian traffic, produced stronger retail or been the prime engines of successful revitalization?

A caveat: the following are my personal observations and conclusions, based on my field visits (often over many years or decades) and limited research efforts that involved internet searches and some personal interviews. Obviously, they are not based on a systematic research effort — that would require resources well beyond those available. Nevertheless. I am hopeful that the reader will find the evidence and arguments presented below convincing.

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York City. This center is the home of 11 world class resident organizations such as The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Jazz at Lincoln Center, Julliard School, Lincoln Center Theater, Metropolitan Opera, New York City Ballet, New York Philharmonic and the School of American Ballet. Conceived as an urban renewal project in the 1950s and parented by the Rockefellers and Robert Moses, it opened the doors of its main buildings during the 1960s.

Though it has had its fair share of problems, I think it is accurate to say that Lincoln Center is generally viewed in all quarters as a successful home and vital asset for its resident organizations as well as a very strong cultural and economic asset for the city as a whole.

In the 50+ years since its inception, the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where Lincoln Center is located, has experienced such a strong rebirth as a residential area that many now argue it is the priciest and most coveted in the city. As the old adage goes, retail follows roofs. Retail on the Upper West Side has changed significantly, but mostly over the last 10 to 15 years, when many prestigious retail chains discovered the area (and rising retail rents forced many independents to close). This retail growth lagged, for decades, far behind the success – and audience attendance – of Lincoln Center, but followed more closely the construction of many new high-end condo buildings.

Lincoln Center did stimulate the development of a cluster of nearby restaurants and bars, but the quality of this cluster and the larger Upper West Side restaurant scene also improved substantially with the neighborhood’s residential resurgence. This suggests that Lincoln Center has indeed been an important revitalization engine, but that its most direct impacts have been to make the neighborhood a more attractive place to live in, not by providing more customer traffic for local retailers, restaurants and bars. It also should be noted that the residential rebirth of the Upper West Side cannot be attributed alone to Lincoln Center. The neighborhood’s proximity to Central Park, Riverside Park and the Midtown Manhattan CBD as well as its subway and bus lines also were important factors. Nevertheless, since it has helped attract a larger and more affluent local residential population, Lincoln Center most probably has impacted positively, if indirectly, on the economic well-being of local merchants. Note that this indirect impact flows independent of the center’s performance schedule.

Lincoln Center’s urban renewal heritage also gave it a design that, combined with the operating hours of its venues, made it difficult for local merchants to benefit from the large audience traffic they generated. As Roberta Brandes Gratz wrote so perceptively back in 2003:

“…Lincoln Center has never really worked. This island of culture stands apart from the city like a fortress, with an elevated plaza on the east offering a lukewarm welcome to one segment of society while concrete walls shut off the less fortunate segment represented by the public housing to the west. Centers like this deaden urban street life, bringing a rush of traffic and human activity all at one time and then lying almost dormant the rest of the day, like a stadium without a game” (1).

To rectify this situation, in 2010, Lincoln Center completed a widely acclaimed project aimed at making the center more permeable and to increase the public’s use of its plaza spaces during the daytime hours when there are no performances. On my daytime visits since 2010, I have observed far more people using these public spaces than I had in the past. This has made the Lincoln Center area “stickier” for visitors, which is bound to benefit local businesses.

Some other large PACs around the nation also suffer from being “islands of culture” with impermeable designs and considerable amounts of time when they are “dark” and inactive. This especially seems to occur when they are inserted into a decayed, low income area. Sports stadiums and arenas inserted into a downtown or city residential area also tend to suffer from being functionally dead for substantial amounts of time. Of interest: the planned renovation of Chicago’s Wrigley Field and the area adjacent to it has components specifically aimed at keeping the area activated on non –game days.

The Paramount Theater, Rutland , VT. Rutland is a small city of about 17,000 people, often referred to as a blue collar, beer drinking type of town, that is also the financial and commercial center of central Vermont. During the 1990s DANTH completed two major reports for the Downtown Rutland Partnership and in both we advocated for the renovation of the Paramount Theater as a way of growing the downtown’s entertainment niche. I last visited the theater sometime around 2000, when it was in its final stage of renovation.

For decades, the region’s economy has been slow growing and it did not fare well during the Great Recession. Through these years, Rutland’s downtown has had its ups and downs. In recent years the challenges have grown with the closings of many of its longtime retail shops as well as its movie theater. (Happily the movie theater re-opened under a new owner who upgraded the projection to digital and 3D and it now appears to be doing well).

After reopening in 2000, the Paramount first struggled to establish itself and then, through the Great Recession, grew in strength. Its annual budget increased from about $700,000 to $1.3 million and the number of performances it presented per year swelled by 75%. The renovated theater gave the community a very attractive and badly needed venue for a wide array of entertainment events — and one local residents could take pride in.

In a recent conversation, I asked Dick Courcelle, the former executive director of the Downtown Rutland Partnership, if what the Paramount does for the downtown today was worth all the blood, sweat and tears that went into its renovation or would they have been better off investing in some other type of project? “It’s absolutely done what we wanted it to do; it was well worth all the effort and resources,” he replied.

In terms of economic impacts, the Paramount’s growing success by itself could not turn the tide for Rutland’s downtown retailers, though it obviously has had some benefits for downtown eateries. Neither could the combination of the Paramount and a rejuvenated movie theater serve as a silver bullet cure for the ills of downtown retailers.

Thinking about the situation in downtown Rutland brought to mind the fact that during the deterioration of the Times Square area here in NYC during the 1960s and 1970s, the many legitimate theaters in the area continued to do a brisk business. Their strength, too, could not prevent severe challenges of social disorder and physical decay from emerging in the neighborhood.

PlayhouseSquare, Cleveland, OH. My association with Ohio goes back to the late 1950s when I went to Kenyon College and then I worked in Columbus for 10 years in the 1960s and 1970s. I have returned on personal and professional visits since then, the most recent being two trips to Cleveland in 2009 and 2010.

Cleveland has long been one of my favorite cities because of its treasures in the arts and sports. The Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland Orchestra playing right across the street in Severance Hall are both world class and worthy of repeated visits. They are part of the University Circle cluster of cultural facilities located about five miles east of the downtown’s Public Square, that also includes the Cleveland Institute of Music, Cleveland Institute of Art, Cleveland MOCA, Cleveland Botanical Gardens and Case Western University.

The city also has many active theatres that date back many decades. For example, the Cleveland Play House, America’s first professional regional theatre, was founded back in 1915. Over the years it has staged more than 1,300 productions that included over 100 world and/or American premieres. For many years, CPH was located on a campus well beyond the downtown on Euclid Avenue near the Cleveland Clinic and about a mile west of the University Circle culture cluster. Recently, it moved downtown to PlayhouseSquare where it will have three venues, including the new Allen Theatre.

PlayhouseSquare is a performing arts center that not only operates eight theaters in downtown Cleveland’s theatre district, but takes on neighborhood real estate development functions and helps local artists obtain needed resources. The theatre district is a 13 to 15 minute walk from Public Square and Tower City Center. It neighbors Cleveland State University. Its spine is Euclid Avenue which runs from Public Square through the theatre district and then goes on through CSU, the Cleveland Clinic and University Circle.

I first visited Cleveland’s theatre district with friends in the mid 1970s and took a closer look at it, at the suggestion of the Greater Cleveland Growth Association., in the early 1980s when I was working on Regional Plan Association’s downtown security and economic development program. On my more recent visits to Cleveland, in 2009 and 2010, I walked about the district and drove through it on several more occasions at various times of the day and evening. My impression was that the district was in good physical condition and appeared to be on an upward revitalization path. Together with the CSU campus, it provided an attractive geographic core upon which additional redevelopment might be attracted. While new eateries were evident, I noted little significant retail. I also observed few pedestrians on the streets, save in the early evenings before showtimes. This, I observed in my field notes, was typical of the theater districts I have visited over the years.

The statistics PlayhouseSquare cites also indicate that it is a popular and successful operation:

- One million + guests per year

- 1,000 events per year

- $4 million per year in contributions.

The revitalization of downtown Cleveland is very much still a work in progress. The strength of PlayhouseSquare is obviously a significant asset in that process, but not the sufficient condition for the downtown’s success. The paths of its positive impacts do not involve generating significantly heightened flows of daytime pedestrian traffic in the district or making the area stickier so visitors will stay around longer. Instead, the direct positive impacts are likely to involve such factors as:

- Making the neighborhoods near the theater district, as well as the larger Cleveland metro area from which PlayhouseSquare draws it patrons, more desirable places to live

- The jobs and salaries it generates for people who live in the region, especially for those in arts-related occupations

- The dollars spent in the metro area by PlayhouseSquare productions

- Making the Cleveland area a more popular tourist destination.

These impacts are primarily regional in nature. The rest of the downtown probably benefits from them in terms of how it fits into the region. On a more local level, PlayhouseSquare’s impacts probably have been:

- Providing an effective redevelopment organization for an important downtown area that also helps find resources to support the creativity of local artists

- Creating a healthier and more appealing commercial area, one that also may be attractive to non-entertainment and non-retail types of businesses

- Stimulating a district restaurant niche

In the past, I have argued that the geographic dispersion of Cleveland’s cultural assets had weakened the downtown. However, the regional character of so many of PlayhouseSquare’s probable positive impacts suggests that the downtown might get its share of such benefits regardless of where a performing arts venue is located — as long as it is within a reasonably easy travel time of the city’s center. The University Circle culture cluster is only about a 12 to 18 minute drive from the downtown’s Public Square or about a 35 minute trip along Euclid Avenue on a Healthline bus.

In contrast, visual arts entertainment venues, such as museums and galleries, can attract substantial amounts of pedestrian traffic downtown during daylight hours, as the lines outside MoMA in Manhattan often demonstrate. Viewed from that perspective, not having either the Cleveland Museum of Arts or Cleveland MOCA located downtown is probably a loss. However, a great number of important art museums are not located in or near their downtown’s core. Many are located in park-like settings that would be difficult to recreate given the existing building densities s and high land costs found in many of today’s downtowns. Moreover, today many museums feel they need very large exhibition spaces such as those in London’s Tate Modern and Paris’s Gare d’Orsay. The former is a converted power station, while the latter used to be a rail station. As these conversions suggest, finding sites to build such large museums on in choice downtown locations is likely to be difficult and very expensive. DIA’s decision to build in Beacon NY instead of Manhattan is a good example of this.

Similarly, gallery owners are often forced by high rents to locate in secondary neighborhoods near the CBD — that they often help revitalize and the resulting higher rents then forces them to move to yet another neighborhood, that they help revitalize….

Some observations and take-aways

If downtown leaders want to attract more daytime pedestrian traffic and keep visitors longer in their districts, formal performing arts venues probably are not the strategic vehicles to use. The number of events they present and when during the day they are presented prevents them from being effective in this manner. Other potential elements of a downtown entertainment niche, such as well activated public spaces, are probably better able to generate more pedestrian traffic and make the downtown stickier.

PACs with island fortress designs make it difficult to establish a pedestrian friendly environment.

Nor are these venues likely to have direct positive impacts on downtown retailers. To some degree the downtown retailers themselves are at fault here — especially those in small and medium sized communities — since they are loathe to stay open into the early evenings. However, theater goers all too often have very little time to stroll and shop before their events start.

Furthermore, performing arts centers are certainly not silver bullet solutions to downtown revitalization problems. They cannot and do not by themselves produce such a result and their successes can have a substantial lead time on the rebirths of the rest of their downtowns.

Many of the benefits produced by these formal entertainment venues are regional in nature and the other parts of the downtown would probably share in them even if they were located elsewhere. Primary, in my opinion, are their abilities to make the area a more desirable place to live and to provide employment and financial support for those in arts-related occupations.

From a more local perspective the creation or rehabilitation of such venues can lead to the physical improvement of one or more buildings as well as streetscapes in a part of a downtown. They also can stimulate the development or growth of a nearby restaurant niche.

Sometimes, as in the case of PlayhouseSquare, these entertainment centers are managed by organizations that have evolved to perform important real estate development and arts support functions. CAPA, in Columbus OH, is another such organization that comes to mind. They are real assets for their downtowns and their communities. They also have greater economic impacts than those venues that just focus on events/performances. Unfortunately, most of the entertainment venues we looked at did not have an organization of this kind.

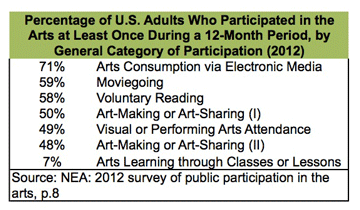

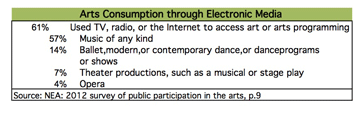

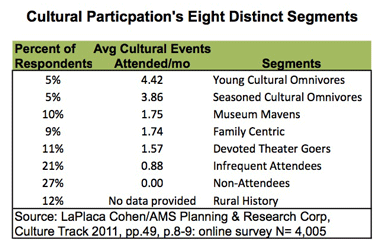

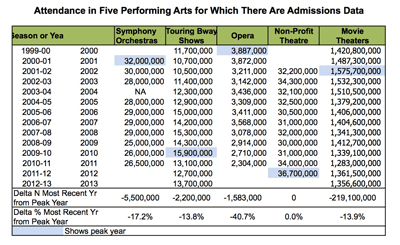

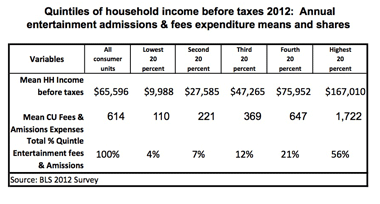

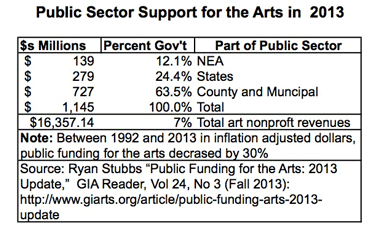

Communities are undoubtedly strengthened when they have attractive venues where residents can come together to enjoy entertainments, including the performing arts. Establishing such venues can be complex and expensive endeavors. Their financial futures are likely to be uncertain given their perpetual needs to have sufficient revenues from earned incomes and contributions at a time when arts consumption is falling, entertainment consumption is becoming increasingly electronic and contributions are harder to obtain. Whether the benefits for the downtown of establishing them in the downtown will outweigh their financial operating risks and high capital investments are issues that require close scrutiny. Also needing consideration are the alternate projects that this capital might be invested in that might produce greater direct benefits for the downtown. The “multipliers” usually trotted out to determine project impacts are ill suited for answering these questions, since their geographic unit of analysis is the region or county, not the downtown.

One way that these formal entertainment venues might increase their direct economic impacts on their downtowns is by incorporating an activated public space into their designs and operations that would attract more pedestrian traffic during the daytime and make their neighborhood stickier. In effect, this what was done by the renovations to Lincoln Center and to the Tines Square theatre district when the city closed much of the Square and Broadway to auto traffic and provided places for people to sit.

© Unauthorized use is prohibited. Excerpts may be used, but only if expressed permission has been obtained from DANTH, Inc.