Posted by N. David Milder

Introduction

This is the first part of the third in a series of articles about the “new normal” for our nation’s downtowns. It focuses on the challenges many downtowns — especially those that are not very large — now face when they decide to bolster their central social district functions by creating and/or strengthening their venues for the performing and visual arts, e.g., performing arts centers (PACs), theaters, cinemas, museums, concert halls, museums, art galleries, etc. Part 1 deals with a general introduction of the challenges, a discussion of who can afford formal entertainments, and changes in the ways governments, corporations and foundations are funding arts projects. Part 2 will turn to changes in the ways Americans attend performing arts events and visit visual arts venues. Part 3 will survey a number of formal entertainment venues.

As noted in an earlier article on the new normal for downtown, successful formal entertainment venues undoubtedly can be strong assets for the downtowns in which they are located. However, the success of such venues has long been uncertain and challenged because, from their get-goes, they are the equivalents of loss leaders for their districts. Most are nonprofit operations that sell tickets to events/performances or charge visitors admissions fees that seldom cover their full costs. For example, among performing arts centers,, be they large or small, only about 40% of their operating costs usually are covered by performance revenues (1). To survive financially,they must be able to tap a number of “charitable” revenue streams, e.g., grants, bequests and other donations from government agencies, corporations, charitable foundations and individuals. This financial dependence makes them vulnerable. Evidence suggests that recent trends have made their financial success significantly more difficult to achieve. Funding for the arts took a big hit during the Great Recession, with its full recovery still in doubt, while research studies have consistently shown attendance at performing and visual arts venues has been changing, in some instances declining significantly for over a decade.

In the performing arts, the fees of performers — be they individuals or groups — are related to their popularity. The ability of a venue to attract them will depend on its seating capacity and the ticket prices it can command. Consequently, as more communities with comparatively limited market area populations and wealth try to develop such venues, they often find that their smaller potential audience base, seating capacity and financial resources require adjustments of their aspirations and a fine-tuning of their programs. In other instances, formal entertainment facilities have been built that just have too much capacity for their market areas or are weakened by new competing formal entertainment centers within their market areas

The arts as an engine of economic growth and downtown revitalization too often seems to have achieved the exaggerated status of a religious credo among downtown advocates or the unrealistic expectation among some of them of being the “silver bullet” solution path to economic rebirth. While the arts undoubtedly can contribute to economic growth, their ability to do so will depend on arts venues and programs being planned and designed in a manner congruent with local needs, behaviors and resources. This challenge is now made more complicated by the fact that these local needs, behaviors and resources may be subject to substantial change.

Consumer Expenditures for Entertainment Admissions and Fees.

Tickets admission fees are an important revenue source for the organizations that operate formal entertainment venues. The less revenues they realize from tickets and admission fees, the more they must rely on obtaining outside funds from government agencies, corporations, foundations, and individual donors. The fees can vary. For example, the Cincinnati Museum of Art has free admission; the Columbus Museum of Art charges $12; the Museum of Modern Art in NYC has a $25 fee; the ticket prices for Broadway shows and tickets for concerts by major attractions can reach well over $100 in prime venues. Obviously, the affordability of these

admissions is a function of both their prices and the incomes of those who would purchase them.

Formal entertainment venues that charge relatively high prices are in a sense targeting more affluent households and a downtown entertainment niche based on a cluster of such venues is likely to be a feature that helps draw affluent households or young people with a lot of discretionary spending power to want to live in or very near to the district. During the 1960s, 70s and 80s attracting such residents was just a long-term goal of many downtowns leaders. Today, in a growing number of downtowns, that goal has been achieved and they are stronger for it. Sophisticated formal entertainment venues that feature major attractions that have substantial admission fees are probably well suited for such downtowns. But, a lot of downtown users, be they current or potential, are being priced out of using these formal entertainment venues.

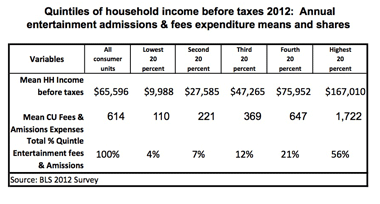

The table above shows that nationally, in 2012, 56% of the expenditures for entertainment fees and admissions came from those in the top 20% of the households sorted by annual incomes. The mean annual household income in this quintile was about $167,000. Those in the top two household income quintiles, with average annual incomes over $75,900, accounted for 77% (56% +21%) of all entertainment fees and admissions.

The general thrust of these findings is not new: the more affluent have long spent more on entertainment, especially the arts. What is new are:

- The emergence of deliberate consumers in middle income households who have reduced discretionary incomes and for whom discretionary entertainment expenditures now are a lower priority than in years past (2)

- The income stagnation and general economic decline of middle income households, a trend that preceded the Great Recession, but recently has become a hot political issue.

The implications for many downtowns are:

- More than ever, ventures to establish new formal entertainment venues must be calibrated in their ambitions, designs and costs to the financial resources of local residents that might be tapped through admissions, fees and donations

- Such ventures are more likely to succeed in communities that have greater residential wealth, especially if capital investments in new buildings, busy event/performance schedules and pricey admissions fees are involved

- In smaller and less affluent communities such ventures are very likely to need strong long-term government subventions and grants from corporations, foundations and community organizations. Most downtowns are likely to fall in this category. In these communities, the presence or absence of very broad support among local residents, the business community and elected officials can be the deciding factor in whether this critical external financial support will be obtained. Often such strong support is mobilized around something or someone that is a source of considerable community pride or identity, such as the artist Grant Wood in the Cedar Rapids (IA) Museum of Art and life on the plains and the Oregon Trail in the Legacy of the Plains Museum in Gering NE.

- Many of the downtowns with weaker financial resources to tap might do well to consider that many Americans see art exhibitions and attend performing arts events not only in museums, theaters and concert halls, but also in parks or other open air facilities, restaurants, bars, nightclubs, community centers, places of worship, college campuses, etc. (See table above).

Grants for Arts Nonprofits

Since the onset of the Great Recession, it has become more difficult for arts nonprofits to get the grants they need from public sector agencies, corporations and foundations. An unanswered question is whether this funding trend will turn around as the nation’s economy improves. Downtown leaders considering the development or expansion of formal entertainment venues might benefit from understanding the topography of these new financial support patterns for the arts.

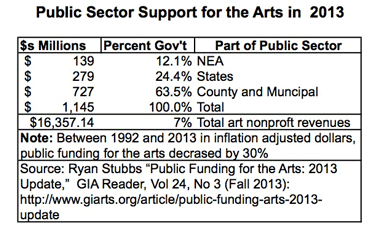

Public Sector Funding. It is important to understand the magnitude of the public sector’s financial support for the arts. It now only accounts for about 7% of the revenues of arts nonprofits nationally and, adjusted for inflation, between 1992 and 2013 public funding declined by about 30%. FY2013 was the first fiscal year since FY2008 that aggregate public sector funding for the arts has increased, but it is still far below former high years (3). The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) only accounts for about 12% of the public sector funding. Its expenditures are not expected to increase significantly anytime soon.

County and municipal governments account for 63% of the public funding for the arts and they recently have shown signs of increasing their funding levels as their economies improve and the impacts of natural catastrophes (e.g., Hurricane Sandy) abate. However, local governments in more densely populated areas often face a large number of requests for arts funding and that usually results in many relatively small grants.

Corporate Support. Unfortunately, data are unavailable for small and medium-sized corporations, but the major findings of a recent report by CECP and The Conference Board on giving in 2012 by large corporations are still illuminating (4): though large corporation giving increased by 42% from 2007 to 2012, funding for the arts decreased by about 40% during that period (5)!

On the hopeful side for a resurgence in corporate arts funding is the fact that giving to the arts remains popular among the corporations; it is the size of their contributions to the arts that have decreased. But, changes in corporate behaviors and preferences suggest that such a resurgence is not likely to happen any time soon:

- Education and economic development have become much more important funding priorities

- More corporations want to make in-kind donations and arts organization may find it difficult to benefit from bulk product donations

- Corporations are increasingly seeing giving as part of their corporate strategy and less as charity

- Corporations are increasingly reviewing their giving from a return on investment (ROI) perspective and nonprofits often do not know how to provide the needed metrics (6)

Foundations. Since about 81% of America’s larger corporations have foundations and they account for about 35% of their corporations’ total giving, there is some overlap between corporate and foundation funding (7).

In 2011, the last year for which there appears to be available data, there was a familiar pattern: while there was a 25.3% increase over 2010 in overall giving by 419 foundations, the increase for the arts was a marginal 0.5%. Here again, the arts’ share of the number of grants remained unchanged (8). However, a “larger share of arts grant dollars provided operating support than most other fields” (9).

Endnotes

1. Harac Consulting, “Evaluation of SOPAC.” October 2011, p.3. http://southorange.org/SOPAC-finalPDF.pdf

2. See: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/downtown-revitalization/the-deliberate-consumer

3. Ryan Stubbs “Public Funding for the Arts: 2013 Update,” GIA Reader, Vol 24, No 3 (Fall 2013): http://www.giarts.org/article/public-funding-arts-2013-update

4. CECP and The Conference Board, “Giving in Numbers: 2013 Edition.”

5. Ibid, page 20.

6. See:ARTSblog » Blog Archive » Michael Stroik. “Corporate Funding Came Back After the Recession, But Did it Leave the Arts Behind”_ (from The pARTnership Movement, an initiative of Americans for the Arts) posted Oct 4, 2013 and ARTSblog>> Judy Belk, “As Corporate Giving Bounces Back, Six Things Nonprofits Need to Know,” posted December 13, 2013.

7. See endnote 4, page 5.

8. Steven Lawrence and Reina Mukai, “Foundation Grants to Arts and Culture, 2011 A One-year Snapshot,” Foundation Center, GIA Reader, Vol 24, No 3 (Fall 2013), http://www.giarts.org/article/foundation-grants-arts-and-culture-2011

9. Ibid.

© Unauthorized use is prohibited. Excerpts may be used, but only if expressed permission has been obtained from DANTH, Inc.