Posted by N. David Milder

Introduction

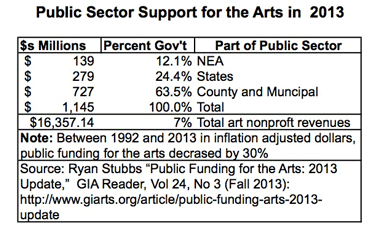

This is the second part of the third in a series of articles about the “new normal” for our nation’s downtowns. It focuses on the challenges many downtowns — especially those that are not very large — now face when they decide to bolster their central social district functions by creating and/or strengthening their venues for the performing and visual arts, e.g., performing arts centers (PACs), theaters, cinemas, concert halls, museums, art galleries, etc. Part 1 dealt with a general introduction of the challenges, a discussion of who can afford formal entertainments and changes in the ways governments, corporations and foundations are funding arts projects. Part 3 will discuss a number of formal entertainment venues as examples and then dive into an update of DANTH’s analysis of what’s happening with movie theaters.

Here, in part 2, the discussion will turn to changes in the ways Americans attend performing arts events and visit visual arts venues. Secondary analyses of two kinds of data will be employed: representative sample surveys done for the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) and other arts related organizations and reports of admissions to various types of arts venues/performances that were obtained from a number of arts sector organizations.

While both types of data can potentially shed light on consumer demand for attending various performing and visual arts events, they are quite different in nature, much as beans differ from broccoli, though both are vegetables. For example:

- While the surveys ask individuals whether they attended various arts events over the prior year, the admissions data report the number of people who attended events put on by arts organizations or visited their venues. The surveys report on characteristics of individuals; the admissions data are characteristics of the organizations or venues

- Translating directly between the two usually is difficult because of a number of issues. For example, the NEA survey may ask about attending classical music concerts, but the best relevant admissions data are only about attendance at concerts done by our largest symphony orchestras. The NEA survey data reports do not detail how often an individual may attend a particular type of arts event, e.g., once to a museum, three times to an opera, six times to a ballet, etc., while the Culture Track report does. The admissions data reports do not detail how many admissions were accounted for by people who had attended multiple times, e.g., subscription ticket holders

- The survey data also tell us, at least by implication and sometimes overtly, about the percentages of people who did not attend each of the arts events/venues asked about. However, memories about attendance over a prior year can lead to an unknown degree of erroneous reporting. The admissions data are not informative about those who do not attend. They simply indicate an important fact for those operating arts organizations and venues: whether admissions have gone up or down – and usually with a good deal of reliability

- Population growth is also an important factor. It is entirely possible that the number of people who are buying tickets for a type of arts events, e.g., chamber music, stays the same over 10 years, but, because of population growth, their proportion of the population would decline.

In this article the survey data will be treated as providing evidence about the proclivities of individuals in the USA to attend various arts events/venues and for explaining why they do so. Though their availability are quite limited, the admissions data will be treated as the best data about actual attendance and ticket sales and as the best indicators of how arts organizations and venues are doing. Obviously, the former should have some impact on the latter, but the paths of that influence are often difficult to accurately identify and detail. However, when both show a similar pattern, e.g., declining attendance and admissions, they can help validate each other’s findings.

The Surveys

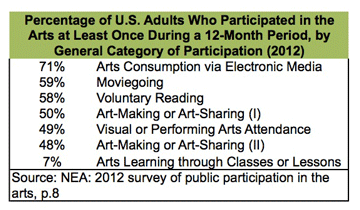

The potential audiences for formal entertainment venues are composed of people who “consume” art by attending performing arts events (plays, operas, concerts) or visiting visual arts venues ,e.g., museums, art galleries, etc. The 2012 NEA survey shows that only 49% of its respondents reported engaging in such attendance behavior in the prior year (see the table immediately below). Movie-going, in comparison, had a 59% attendance rate.

Looking more closely at specific arts, the NEA survey showed that in 2012 only relatively small proportions of respondents attended them: classical music 8.8%; jazz 8.1%; dance other than ballet 5.6%; ballet 2.7% and opera 2.1% (see table immediately below). This suggests that the potential audiences for such arts events are comparatively small, though they will be higher where they are geographically clustered, e.g. affluent neighborhoods.

Moreover, when compared to the findings of a 2002 NEA survey, it appears that there has been a general decline in attendance: classical music -24%; jazz -25%; dance other than ballet -11%; ballet -31% and opera -34%. This would indicate that the audiences for these performing arts are not just relatively small, but they are also dwindling when looked at on a percentage basis.

The National Arts Index Report 2013 (NAI) uses survey data gathered from 210,000 individuals by Scarborough Research to demonstrate that attendance at art museums between 2006 and 2011 was below 2003 levels, down by about 8% in 2011 (1). Moreover during the 2003-2011 period, museum attendance never regained their 2003 level.

Some have argued that the decline in arts attendance revealed in the NEA’s 2008 survey was a result of the Great Recession. However, 2012 is three years after the recession’s official termination, yet the decline continued. The economy is undoubtedly a factor, but probably through economic forces that were in play prior to the recession’s onset and continue to have impacts today. This view will be supported below when the admissions data of arts venues are discussed.

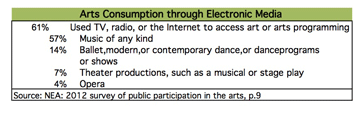

One reason for this decline may be the growing consumption of performing and visual arts through electronic media. For example, the 2012 NEA survey found that 61% of the respondents used TV, radio or the Internet to access art or arts programming (see table above). A closer look shows that 57% consumed music of any kind via the electronic media; 14% accessed ballet, modern or contemporary dance or dance programs or shows; 7% theater productions and 4% opera. The numbers for dance and opera rival those who attended such performances in person in theaters or other physical venues.

In the near future, technological innovations may increase this diversion to e-attendance. For example, Mark Zuckerberg posted the following comment to explain Facebook’s purchase of the maker of the Oculus virtual reality headset: “When you put (the headset) on, you enter a completely immersive computer-generated environment, like a game or a movie scene or a place far away. The incredible thing about the technology is that you feel like you’re actually present in another place with other people” (2). The potential for using a virtual reality headset to attend sports events, plays, concerts, operas, etc. appears real; the degree to which it will be realized remains unknown. If not Oculus or some other virtual reality device, then some other technology may emerge to drive more e-attendance. This Pandora’s box has been opened. Also, it should be remembered that technological impacts on arts attendance are not a new phenomena: back in the 1950s TV viewing drastically decreased movie attendance and changed the way that industry works, but we still keep going to movie theaters.

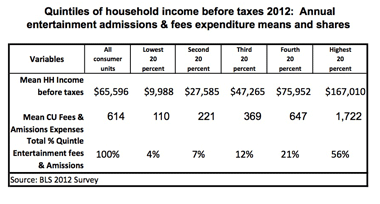

Other factors are also very important in determining attendance at arts performances. As the Culture Track 2011 report noted: “Decisions about whether to participate in the arts are driven primarily by cost, programming, and convenience. This is true at all ages and income brackets” (3). This report was also based on a large national survey with 4,000+ respondents. The NEA surveys also show that age, education and ethnicity can be factors, but it notably neglects to discuss the impacts of income. Education is probably acting somewhat as a surrogate variable for income in the NEA analyses because of their high correlation. In today’s economy, one might reasonably argue that admission cost is a major determining factor for persons who are not wealthy and who do not have heaps of discretionary dollars to spend.

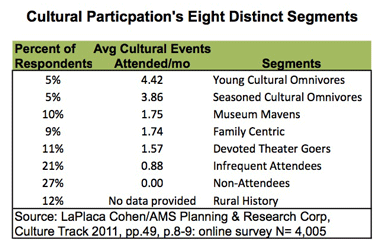

The Culture Track 2011 study did identify a number of high arts consumers: the young cultural omnivores — likely the young hipsters with lots of discretionary dollars to spend — and the older seasoned cultural omnivores, who appear to be older and affluent. As the word “omnivore” implies, both like to attend a variety of arts/cultural events. However, together, they represent only about 10% of the Culture Track survey’s respondents. Then there are three segments that specialize in the type of cultural events they prefer to attend: the museum mavens just like to visit museums, the devoted theater goers just like to go to the theater and the family centrics prefer to attend mostly child friendly events. The specialist consumers’ attendance rate is about half of that of the omnivores. The specialists account for 30% of the Culture Track survey’s respondents. Forty-eight percent of the survey’s respondents are non-attendees and infrequent attendees, and 12% are in the rural history segment that basically is lives in very rural areas, far from major cultural venues.

The Culture Track survey also found that decreasing attendance was being influenced by the general economy and manifested in the reduced number of events culture consumers went to, not in a reduction of the number of people who are culture consumers.

These findings suggest that besides about half of all adults being hard or impossible to attract to cultural events, substantial portions of those who are culture consumers will opt out if a venue does not put on the particular type of cultural event/performance they prefer. They also show that the economy is having a negative impact on how often American cultural consumers attend cultural events.

It should be noted that the NEA’s 2012 survey did find art events that were attracting more people, e.g., 5.1% reported going to events where Latin, Spanish salsa music was played compared to 4.9% reported in its 2008 survey. The NAI report, again based on Scarborough Research survey data, shows that attendance at “live popular music,”– which includes country, R&B, rap, hip-hop and rock music performances — equaled or exceeded the 2003 level every year but one between 2004 and 2011. Indeed in 2011, attendance at live popular music events was 14% above the 2003 level (4). This reflects another pattern the surveys agree on: some arts forms are attracting stronger audiences. However, the “high brow” culture/arts forms, e.g., opera, ballet and classical music are not among them.

For those believing that the performing arts can be a silver bullet solution for downtown revival, the NEA and similar surveys indicate a changing and too often dwindling potential audience. They also suggest that the demographic characteristics of a market area and its prevailing lifestyle segments can have a big impact on potential attendance for each of the various types of performing and visual arts events. Formal entertainment venues are likely to be intensely challenged when they try to find and capture audiences for their programs and events. Consequently, the critical ticket and admissions sales portion of their revenues seem to have become more uncertain, just as have their government funding and grants from corporations and foundations.

REVISION 041214: Since the initial posting of this article DANTH has come across survey information released by the Broadway League, “The Audience for Touring Broadway: A Demographic Study 2011 -2012,” which had the following findings:

- “Seventy percent of attendees were female.

- The average age of the Touring Broadway theatregoer was 50.5 years.

- Eighty nine percent of Touring Broadway theatre goers were Caucasian.

- Seventy-eight percent of the audience held a college degree and 30% held a graduate degree.

- Forty six percent of national theatre goers reported an annual household income of more than $100,000, compared to only 21% of Americans overall.

- Thirty one percent of respondents were subscribers to the “Broadway Series” at their local venue.

- On average, Touring Broadway attendees saw 4 shows per year.

- Women continued to be more likely than men to make the decision to purchase tickets to the show.”

Performing and Visual Arts Admissions

To research annual levels of admissions at various types of performing and visual arts venues, DANTH reviewed relevant data posted online by such organizations as the League of American Orchestras, the Theatre Communications Group, the National Association of Theatre Owners (movie houses), The Broadway League, the American Alliance of Museums, Opera America, et al. Some of the reported data are not specific enough for the needs of the analysis in this article. For example, the Alliance of Museums surveys its museum members asking if attendance went up or down in the reporting year within specific percentage ranges. It does not collect anything like “counts.” Most of the other organizations survey their membership about admission counts and then on the basis of the reported data extrapolate out to the total number of organizations in their field. For example, the Theatre Communications Group, for its 2012 report, collected data from 178 theaters and then used those results to make an estimate of the annual admissions of 1,782 nonprofit theaters. Some of these organizations appear to have ceased publishing data about admissions.

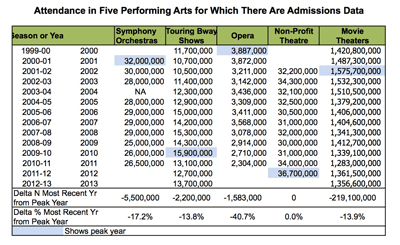

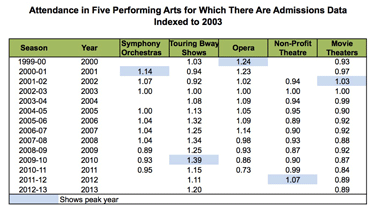

The analysis below only covers five of the six types of performing arts for which we could find count-based admissions data: movie theaters; symphony orchestras; touring Broadway shows; opera, and nonprofit theaters . Although the desired data are available for Broadway shows staged in Manhattan’s theater district, they were not included because of their geographically confined relevancy.

One of the things to take away from the above table is the relative sizes of the absolute admissions numbers for each of the arts categories. Attendance at movie theaters, which is in the billion+/yr range, simply dwarfs the combined attendance of the other four arts categories. The opera admissions are far, far smaller than those for the symphony orchestras and nonprofit theaters. For downtown leaders who want performing arts to drive more traffic downtown, the implications seem obvious.

Attendance for symphony orchestras, opera and movies began their declines well before the onset of the Great Recession. This strongly suggests that other factors were influential. On the other hand, attendance for touring Broadway shows has certainly varied over the years, but usually has been strong. The non-profits theaters’ admissions did hit bottom during the recession, but they have since recovered and actually peaked in the most recent year for which there is data, 2012.

The above table helps to see historic trends more easily by indexing the attendance statistics for each category to the 2003 attendance:

- Movies. Movie attendance had an average index score of .923 between 2000 and 2013. It topped out historically in 2002 at 1.03 and then followed a bumpy downward path to .84 in 2011. That is a percentage decline of about -18.4%. However, attendance bounced back with about a 6% increase in 2012 over 2011 and then ebbed slightly, 0.40%, in 2013 (5). That still left movie attendance about -14% below its 2002 high. As movie attendance has declined, research by Pew found that Americans watch five times as many movies at home than they do in movie theaters — and that study predated Netflix’s entry into the movie and TV show streaming business (6). To help stem the decline, Hollywood has increased its annual movie production by about 39%, from 478 in 2000 to 665 in 2012. Over this same period, the number of indoor movie theaters declined by 18.8%, the number of indoor movie screens increased by 9.4% and all distribution and projection functions went digital. Since movie house ticket sales only account for a fraction of movie studio revenues — under 15% — a growing number of movie moguls are pressing for new films to be released digitally at about the same dates as they are screened in traditional theaters

- Touring Broadway Shows – Although this category shows about a -13% decline in 2013 from its peak year in terms of absolute attendance, the 2013 attendance is still 20% above the 2003 benchmark year, and it has the highest average indexed attendance score presented in the above table, 1.14. Its index scores exceeded the benchmark 1.0 in 12 of the 14 years for which we have data, peaking in 2010 at 1.39. The index scores were relatively high in the preceding 2006 and 2009 period, with scores of at 1.34 and 1.25 during the two recession years. Its index score has not been below 1.10 since 2004. Attendance is significantly impacted by the number of plays on the road and the lengths of their runs. For example, for Broadway shows there is a .69 correlation between the number of playing weeks in a year and attendance. That can statistically explain about 47% of the annual variation in attendance. From the data the Broadway League publishes about gross revenues of the touring shows, it appears that in 2013 the average revenue per admission was $64.01 (up 22% since 2003). If the average ticket price was around that figure, then a lot of folks probably cannot afford to attend touring Broadway shows. Not all downtown theaters can attract a touring Broadway play; they must have an ability to generate ticket revenues that are commensurate with the size of the production’s cast and costs.

- NonProfit Professional Theaters. There were an estimated 1,782 of these theaters in the USA in 2012, and most were not very large– they averaged just 174 admissions per performance. For the 11 years that there is available data, the attendance index scores for this arts category are below 1.0 in nine of them. But, the most recent score was its highest, 1.07 for 2012, and it followed a 0.99 score in in 2011 that was a .09 improvement over 2010. These theaters get about 52% of their revenues from earned sources and 48% from contributions. Using the published expense data and dividing it by attendance indicates that there is about $54.11 in expenses associated with the average admission. The earned income, probably from ticket sales, would cover about $28.26 of the average admission cost, with contributions covering the remaining $25.85. Theater tickets in the $30 range are likely to be affordable to many more people than tickets costing $60+. But, needing this audience subvention certainly contributes to pushing about 50% of these theaters to operate in the red (7).

- Opera. Between 2000 and 2011, opera attendance dropped off dramatically by about 40%. The decline has not been linear. Between 2000 and 2003, well before the recession’s onset, attendance fell by about 24%. It’s attendance index score then increases to 1.09 in 2004 and wobbles up to 1.14 in 2007. It then continues to decline down to 0.73 in 2011, the final year for which we could find data. The difference between the 2000 and 2011 index scores is a stunning 0.51. However, this decline was not linear: an important attendance decline occurred well before the recession, and another and stronger decline started when the pre-recession financial crisis began to emerge.

- Symphony Orchestras. For the years the DANTH team was able to find relevant data, attendance at concerts of 187 symphony orchestras peaked in 2001 and 2002, with index scores of 1.14 and 1.07. It then dropped to 1.0 in 2003 and 2005, well before the Great Recession. Attendance actually rose to 1.04 in 2006 to 2008 as the financial crisis and the the recession set in, but then incurred a substantial drop in 2009 to its lowest index score, 0.89. Attendance recovered somewhat in 2010 and 2011 with index scores of 0.93 and 0.95, showing something of a recovery trend. But attendance in 2011 still was about 7% off the 2003 benchmark and about 17% below the 2001 peak. While the Great Recession probably had a significant impact on attendance, the drop in 2003 and 2005 suggest that other factors also might be at work. Within the field, there has been much heated debate about whether attendance has ebbed because the classical repertoire has become too limited, boring or inaccessible and whether substantial efforts are needed to expand its audience by attracting more people from a wider range of ethnic, income and age groups. However, a number of observers have argued that even if attendance may have fallen, the quality of the players and orchestral performances has been very high, and the popularity of classical music has grown in such places as college campuses (8). This raises the question: what, then, are the factors that have been pushing admissions at symphony orchestra concerts down, if it is not the quality of the performances and other than recessionary impacts?

The table immediately above takes the absolute admissions data from the table “Attendance in Five Performing Arts for Which There Are Admissions Data” and indexes/standardizes it to the national population in each of the years covered. It is, mathematically, something akin to turning them into percentages. The results are per capita admissions by year of each of the arts categories in the table. Some things to note:

- Opera and a classical music subset, symphony orchestras, display strong reductions in attendance in the most recent years for which there is data from their peak years, -46.3% and -24.3 % respectively

- These are significantly higher declines than those revealed by the analysis of the absolute attendance data, -40.7% and -17.2%

- While the touring Broadway shows also show from this perspective a stronger decline, the per capita attendance is still well above the benchmark year

- Movie attendance also shows a greater decline than the absolute attendance numbers, -21.7& compared to -13.9%; its most recent per capita attendance is well below that of the benchmark year

- Non-profit theaters had their highest admissions ever in 2012, but the per capita admissions in 2003 were just barely higher, 0.1182 to 0.1169.

Take Aways

- This analysis has looked from several perspectives at the issue of what has been happening to the attendance levels for various types of performing and visual arts venues over the past decade or so.

- The contention that attendance patterns are changing significantly seems hard to refute.

- The contention that forms of “high brow” culture such as opera, classical music and ballet have suffered attendance declines also appears to be supported by the numbers

- Art forms associated more with popular culture, e.g., live popular music performances, are those that seem to be doing best. However, movie attendance is not what it has been, despite huge efforts to buttress attendance by by providing more movies per year on more movie screens and using 3-D and IMAX projection systems to substantially enhance the viewing experience

- The impact of technology to provide new ways of e-attending performing arts events or visiting museum art collections (MoMA, the Met, the Louvre, the Smithsonian, the Whitney, etc. all have them) is undeniable, but the extent and pattern of that impact is still uncharted. However, what the movie attendance shows — remember we watch 5 times as many movies at home or on our e-devices than in cinemas — is that to a substantial degree we still want to watch/see arts events in person with other people. That does not mean that there will not be adverse impacts — just think of all the closed movie theaters, about 10% of them, some say, due just to the conversion to digital projection and distribution

- Whether or not these audience churns and declines reflect a cultural dumbing down of our population or whether performing arts repertoires have become stale or their performance levels waned are irrelevant issues for downtown leaders who want to enhance their central social district functions by building a stronger entertainment niche

- What is important are the changes in arts audience behaviors. They increase the uncertainty of existing arts organizations’ earned incomes and definitely will be affecting the economic feasibility of projects to create new formal entertainment venues. Creating such formal arts venues is seldom associated with cheap capital costs

- Regarding the new projects, given the probable capital expense, the uncertainties associated with earned income and the inherent tendency to best serve an audience that has a significant amount of discretionary dollars to spend, some downtown leaders might do well by considering other types of projects to enhance their entertainment niches. These projects might take the form of new vibrant public spaces that are: open to all; where plays and movies can be shown, but focused mainly on maximizing informal entertainment opportunities; either free or low-cost; designed to capitalize on people watching; where participants are both the performers and the audience.

Endnotes

1. Americans for the Arts. National Arts Index: 2013 Report, pp.149, p.67

2. Ibid., p.64

3 See: http://www.businessinsider.com/zuckerberg-why-facebook-bought-oculus-2014-3#ixzz2x1lgtLVO

4.LaPlaca Cohen/AMS Planning & Research Corp, Culture Track 2011 Market Research Report, pp.87, p.7

5. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/

6. Pew study cited in:https://www.ndavidmilder.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/trends_p1_films_08.pdf

7. The data in this section are drawn from Theatre Facts. It has been published annually by The Theatre Communications Group since 2000. See the 2012issue at:http://www.tcg.org/pdfs/tools/TCG_TheatreFacts_2012.pdf

8. See for example: http://classicalvoiceamerica.org/2014/03/07/campus-concerts-rebuff-notion-of-classical-decline/ and http://www.city-journal.org/2010/20_3_urb-classical-music.html . Thanks to Andy Menshel for bringing them to my attention.

© Unauthorized use is prohibited. Excerpts may be used, but only if expressed permission has been obtained from DANTH, Inc.