By N. David Milder

“Aeschylus and Plato are remembered today long after the triumphs of Imperial Athens are gone. Dante outlived the ambitions of thirteenth century Florence. Goethe stands serenely above the politics of Germany, and I am certain that after the dust of centuries has passed over cities, we too will be remembered not for victories or defeats in battle or in politics, but for our contribution to the human spirit.”

–John F. Kennedy

Back in 2014 and 2015, I wrote a number of articles related to the development of downtown arts and entertainment niches (1). Their thrust was that while developing and operating formal enclosed venues for arts and entertainment uses can strengthen downtown revitalization efforts, they also are often fraught with organizational complexities, financial difficulties and negative trend headwinds that are overlooked by ardent supporters of arts projects. The result is too many underperforming or even failing formal arts venues. Moreover, many of the purported benefits of these arts venues might be more reliably and cheaply provided by well-activated public spaces, parks and third places.

I recently attended a very good conference that was aimed at mainly small and medium-sized communities located in rural and suburban areas. However, I came away very worried by the strong and incautious advocacy of the arts as a small town revitalization engine I encountered there. These arts advocates, some new to the faith, did little to indicate the wide range of challenges such a strategic approach is likely to encounter. Nor did their audience seem to have any awareness of such challenges. Many of them seemed to be eagerly looking for something to take the place of the weakening retail in their downtowns, and the arts appeared to be a very appealing solution. Alas, arts projects may be highly desirable, but it is foolish to assume they are quick or easy to do.

Part of the problem had to do with how most of our conferences use success stories for their content spines. It seems that in contrast to Silicon Valley, we in the downtown revitalization field only learn from our successes, not our failures. However, it also may be due to the fact that not many downtown leaders and experts are providing the needed information. This has prompted me to update my research and write this article. Let me be clear: its objective certainly is not to rail against the arts as an economic asset. It is, instead, to help downtown leaders and stakeholders better calibrate their arts development efforts, so that more of them will succeed, because they properly mesh with local resources and opportunities.

One reason that great care needs to be taken when using the arts as a key element in a downtown revitalization strategy or program is the hybrid earned/contributed incomes business model that nonprofit arts organizations use. It is more complex and consequently requires a wider set of management and leadership skills than the simpler for profit model used, for example, by the organizations that own and operate our movie theaters or put on our touring Broadway shows. The hybrid arts organizations are both charities with a built-in need for substantial contributions from individuals, businesses, foundations and/or government agencies as well as businesses that sell arts products (including performances and exhibitions) to earn incomes. Unfortunately, as events in recent years have demonstrated, these contributions are very dependent on economic and political conditions and can be very erratic. This model has a high level of financial failure as measured by having budget deficits. The use of the hybrid business model is a de facto admission that these arts organizations cannot cut it financially on just their earned incomes. Some may argue that the hybrid model benefits from greater diversification than the for-profit model, but that may mean, with tight budgets and unreliable donors, more ways to fail than to be safe.

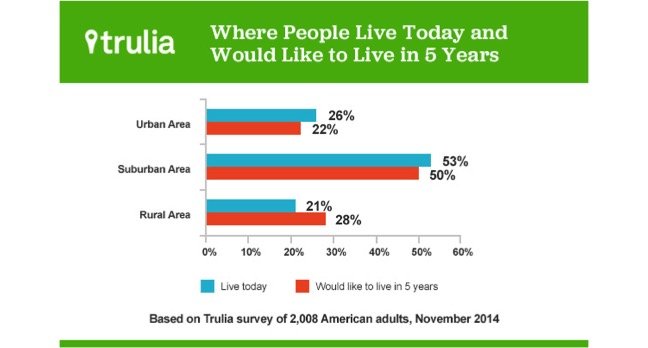

On the earned income side, things these days have not been easy either. For over a decade, all types of arts organizations, be they nonprofit or for profit, have been facing a disconcertingly changing pattern in the way Americans participate in the arts. More arts participation is being done electronically. Some of the performing arts – e.g., opera, ballet, movies, symphony orchestras, jazz – have reported significantly reduced attendance, while others, such as Broadway shows and nonprofit theaters, have experienced serious and sometimes financially stressful fluctuations in attendance. “High culture” performances were losing popular support, while “low culture” entertainment performances (salsa music, comedians, rock bands, rap groups) were gaining popularity. As a consequence, many renovated theaters and new PACs have had hard financial times because they couldn’t find the right programming for their market area. They also had not done their homework.

While I acknowledge that arts venues can strengthen a downtown’s central social district functions and that credible research has demonstrated that they can have positive economic impacts, the impacts on their downtowns may not be as glorious as purported in project proposals – or conference presentations. My research has shown that too often the potential positive impacts of arts projects on downtowns are grossly misunderstood, and their actual magnitudes often go unmeasured, though wrongly assumed to be large. On the other hand, their negative impacts are far too often conveniently overlooked, even if easily noticed and measured.

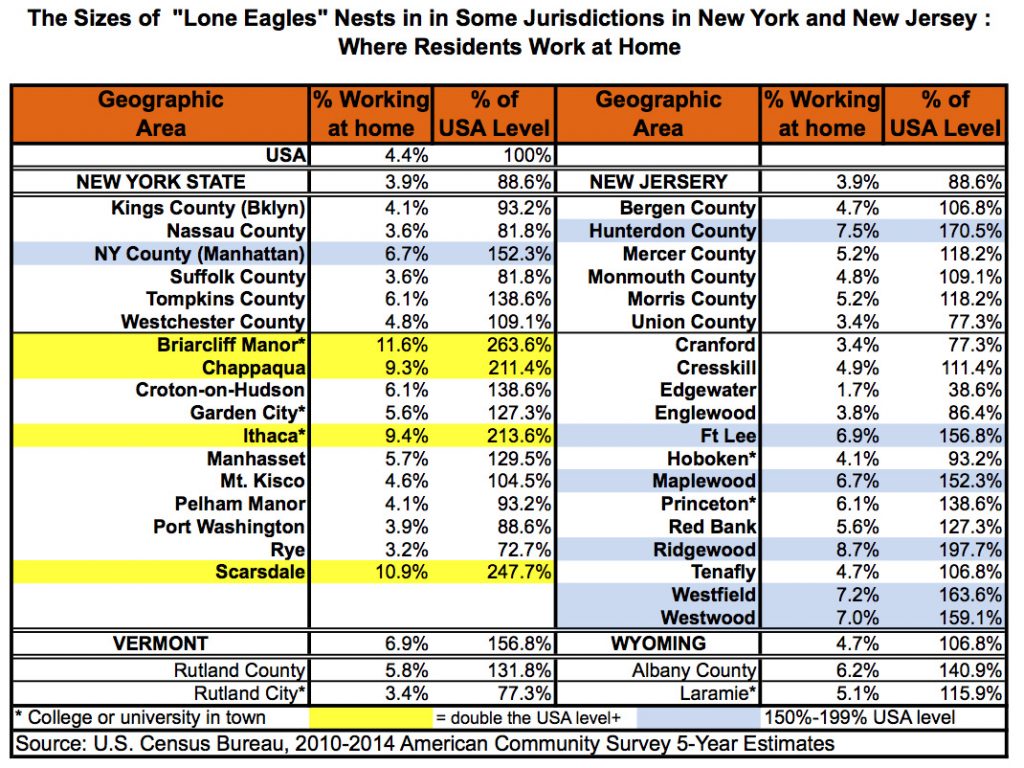

The demographics of a downtown’s market area have an enormous influence on how many visitors and the amount of the financial contributions downtown arts venues can attract. Arts advocates too often put the cart before the horse, focusing on purported positive impacts, while not looking closely enough at the demographics that influence an arts project’s or an arts organization’s viability.

Another hard truth is that many small and medium-sized communities probably will have stronger positive impacts on their downtowns and a consequent higher ROI by investing in strongly activated parks and public spaces as well as in the micro businesses of local artists and artisans, than in building and operating covered venues for the performing arts and museums.

The Lack of Proper Calibration of Aspirations to Available Resources and Opportunities

Through my travels, arts consumption and professional activities, I have encountered many arts organizations that are in such a precarious financial situation. Some are huge with budgets over $100 million, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC. Others are large and well-known entities in our big cities such as the numerous symphony orchestras that recently have been downsized and/or re-organized. There are also the PACs that have struggled in suburban communities such as Englewood, NJ, South Orange, NJ, and White Plains, NY. Many small downtowns have museums with very limited operating hours or theaters and cinemas on the verge of failure. In dense, modest-income urban areas, large amounts of community energy and scarce funds have been used to develop attractive arts venues, such as the Jamaica Performing Arts Center in Queens, NY, that are largely underutilized and need deep subsidies to survive. Stories of local governments having to step in to save the day are easy to find: e.g., the city to save a museum in Gering, NE; the county to save a PAC in Englewood, NJ. I could add many more examples to this list, but won’t for the sake of brevity.

My takeaways from all of these examples were:

- All suffered from the same underlying problem: their aspirations were not properly calibrated to the resources and opportunities available to them. Their eyes proved bigger than their stomachs or wallets.

- Careful calibration is required to a large degree because of the shaky nature of the business model used by most arts organizations (and other nonprofits) and a changing environment that has made both earned and contributed incomes significantly less reliable.

The Hybrid Business Model Used by Arts Organizations Has Major Inherent Problems

A Structural Propensity to Have Deficit Annual Budgets. Roland J. Kushner and Randy Cohen in their National Arts Index 2016 paint a picture of arts organizations that should be carefully considered by any downtown leaders who are thinking about making the arts or an arts project a central component of their revitalization efforts. A very large number of arts organizations do not have break-even budgets and consequently, raise concerns about their long-term sustainability. According to Kushner and Cohen:

“Arts nonprofits continued to experience financial challenges: The percentage of arts organizations operating at a deficit has ranged from 36 percent in 2007 (during a strong economy) to 45 percent in 2009 (the deepest part of the recession). In 2013, a time of improved economic health, 42 percent of arts nonprofits still failed to generate positive net income—a figure that raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of arts organizations that are unable to achieve a break-even budget. Larger-budget organizations were more likely to run a deficit, though no specific arts discipline is particularly more likely to run a deficit…. (I)t is clear that the budget fortunes of nonprofit arts organizations got worse during the Great Recession and have been very slow to recover.” (2)

Consequently, it would seem very reasonable and very prudent for downtown leaders to be extremely cautious about using an economic sector populated by organizations with a very high propensity for financial instability as an engine of downtown revitalization.

The Proven Long-Term Uncertainty of Their Revenue Streams. The hybrid model is based on revenues coming from many very different sources and obtained through different means. According to Americans for the Arts: “Support for the nonprofit arts is a mosaic of funding sources – a delicate 60-30-10 balance of earned revenue, private sector contributions and government support.” (3) Here’s a more precise breakdown by AftA:

- 60 % Earned Income

- 31% Private Sector Contributions

- 24% Individuals

- 4% Foundations

- 3% Corporations

- 9% Government support

- 4% Local Government

- 2% State Government

- 3% Federal Government

Other research has found a slightly different funding mix. The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), using data from the Urban Institute and Census Bureau for 2006-2010, found that the revenue sources for nonprofit performing arts groups and museums were:

- 55.1% Earned Income, Interest And Endowment Income

- 38.2% Contributions From Individuals, Foundations & Corporations

- 20.3% Individuals

- 9.5% Foundations

- 8.4% Corporations

- 6.7% government grants

- 3.3% local government

- 2.2% state government

- 1.2% federal government (4)

Earlier, pre-Great Recession estimates showed that earned incomes accounted for about 50% of the revenues of nonprofit arts organizations.

Perhaps it is best to amend AftA’s statement to read that arts organization funding has been a delicate balance of 50% to 60% earned income, 30% to 40% private sector contributions and 10% or less from government support.

In any case, there is general agreement on the types of funding sources and the fact that there are many of them. In a 2012 study of the factors that challenge the financial sustainability of nonprofit organizations, the RAND Corporation’s authors placed at the top of their list:

“Risk of reliance on external funding sources and streams. In contrast to for-profit organizations, nonprofits in the United States depend on diverse sets of funding sources and streams of funding to sustain their operations. Most nonprofits receive funds from multiple sources (e.g., government, foundations, private donors) and streams (e.g., grants, contracts, membership fees). Substantial cutbacks in both government and foundational funds suggest that nonprofits should develop or revisit their fundraising plans to support financial sustainability.” (5)

At the level of the individual organizations, there can be additional variation. For example, The Goodspeed Theater in East Haddam, CT, gets about 26% of its revenues from contributions and about 57% earned income, while the Weston Playhouse Theater, in Weston, VT, gets 63.4% of its revenues from contributions and about 29% from earned income (6).

Both theater managements will differ from for-profit arts organizations in their need of staff and board members who are adept at marketing to individuals and organizations that are potential financial donors. The skills involved are quite different from marketing tickets to a movie, Broadway play or ice show to the public. Even the skills needed for obtaining grants from government agencies can be quite distinct from those required to network with and cultivate very wealthy donors.

Does the Weston Playhouse’s greater reliance on contributed income over earned incomes make it structurally more financially vulnerable than the Goodspeed that relies more on its earned income? It seems very likely to me.

Demographics Really Count

Annual Contributions to the Arts by Household Income (table from a report done for Google)

Re: Contributed Incomes. After earned incomes, contributions by individuals are the most important source of revenues for arts organizations nationally. Research has shown that contributions to the arts correlate with household incomes. The table above was generated in a 2007 report for Google that was done by the Center for Philanthropic Giving at Indiana University. It shows that 93.4% of all charitable giving to arts organizations is from households with annual incomes over $200,000. Among the vast number of households with incomes beneath $100,000, just 6.2% contributed to the arts, and they accounted for just 4.4% of all contributions to the arts by individuals.

While I strongly suspect that this report might have met with criticisms, I think it is possible to more generally restate its findings to the more certainly defensible conclusions that:

- Most of the dollars contributed by individuals to the arts come from rather affluent households

- Financial contributions to the arts increase with household incomes, and the increases get larger as the incomes get bigger.

Poor and small- and medium-sized communities will likely have below average percentages of very affluent households who are either year-round residents or second home owners. The ability of their arts organizations to have 30% to 40% of their revenues come from private sector contributions is consequently strongly impeded. Moreover, they consequently are relatively more dependent on winning contributions through grants from foundations, businesses and, especially, government agencies.

Re: Earned Incomes. The potential consumer dollars that arts organizations can tap is calculated by the number of people in their market area and their annual expenditures for arts performances, exhibitions, and products. Small- and medium-sized communities probably will have the obvious inherent problem of a market area that is not densely populated. An additional potential problem is, again, their probable comparatively low household incomes.

As can be seen in the above table, nationally, households with incomes over $103,057 account for 54.8% of all expenditures for entertainment fees and admissions, which includes admissions to arts and cultural venues such as theaters, cinemas, PACs, concert halls, etc. Adding the households with incomes over $62,587 shows that the most affluent 40% of our households account for 75% of the expenditures for entertainment fees and admissions. Arts venues in market areas lacking substantial numbers of such households, especially those in the top income quintile, will be hard pressed to have substantial revenues from their paid admissions. Small- and medium-sized communities are likely to have such market areas with relatively few affluent households. They are likely to be absent in poor communities.

Endowment and Interest Incomes. The NEA’s study found that 14% of the annual revenues of performing arts groups and museums come from these two sources. Such arts venues in poor or small- and medium-sized towns, with relatively small budgets and in perennial hand-to-mouth financial situations are not likely to have much interest income and are even less likely to have any endowments.

The Ups and Downs of Business, Foundation and Government Funding for the Arts Matters. Arts organizations are very sensitive to even slight variations in their philanthropic funding levels. As Randy Cohen at Americans for the Arts wrote in 2015: “We pay close attention to philanthropy because even small fluctuations in contributed revenue can be the difference between an arts organization broadening its reach or facing a deficit.” (7)

Moreover, charitable giving for the arts has a history of significant fluctuations. Here, again, is an astute observation from Cohen: “The arts compete well for charitable dollars in good times, but tend to struggle in a down economy as many funders move their giving to what they perceive are more pressing human service needs.” (8)

The above table shows how total contributions to arts nonprofits varied annually from 2008 to 2016 (9). In two years there were decreases, but even when there were increases, the amounts could vary from just 1.6% to a more robust 15%.

Funding From Foundations. After individuals, foundations are the next most important source of contributions to arts organizations. The National Arts Index for 2016 found that:

“Along with the number of grants, foundation dollar amounts increased from 2001 through 2012 only modestly, by six percent to $2.2 billion, when measured in current dollars; this leads to a decrease of about 18 percent when adjusted for inflation.” (10)

Major Corporate Giving. Data from the Conference Board indicate that contributions from large corporations declined by about 51% from $418 million in constant dollars in 2006 to about $215 million in 2010. However, it has rebounded somewhat lately, about 27% between 2013 and 2015 (11). Smaller firms, of course also contribute to the arts, but at lower levels in terms of numbers and amounts (12).

Government Funding. At this point in time, June 2017, the future of the NEA is again very much in doubt. However, as some conservative political observers have been quick to note. It accounts for only a relatively small percentage, about 1.2%, of the funding of our arts organizations.

State and local government arts funding responded to the Great Recession by dipping significantly between 2008 and 2012, but they have followed a positive, if uneven, trajectory since then.

However, looking at a longer time frame shows a different picture. As Ryan Stubbs, another astute observer of the arts funding scene, has noted about the 1994-2014 period:

“Although the nominal increase over the past twenty-one years is positive, the landscape for public funding for the arts in this time period is much bleaker when accounting for inflation. In fact, after adjusting for inflation, public funding for the arts has decreased by more than 30 percent in this same period.” (13)

Concerns about government funding are arguably diminished because they account for fewer than 10% of all arts organizations’ funding. However, my observations suggest that, in many small- and medium-sized communities, when a significant local art organization is on the brink of financial collapse, it is a municipal or county government that steps in to save the day. Such interventions can have critical impacts on the arts organization and the whole community it serves. I wonder what would happen if local governments really did stop making such bailouts?

One thing seems certain: any arts organization that predicates its future financial well-being on continually receiving government grants has placed itself in a very risky situation.

Budget Size Matters.

Most arts organizations are small, with revenues under $25,000. In 2012, about 63% of the nation’s estimated 110,000 arts organizations had revenues below $25,000. (14). A study done in 2017 estimates that there were 39,292 nonprofit arts and cultural organizations in the USA that had revenues over $50,000 (15). This means most art nonprofits will have little or no staff and will very likely either have very few performances or very few hours when they are open to the public. If they rent street level storefronts, when closed, they function as dead spaces that detract from their block faces walkability, while also signaling a lack of vibrancy.

Even when budgets get somewhat higher, the impacts are not likely to be significantly large. For example, the Wyoming Territorial Prison, a museum in Laramie, WY, (population 32,000) reported revues of $90,290 on its IRS Form 990 in 2015, but its annual visitation is about 16,000 (averaging about 2,700 per month) during a season that lasts from May 1st through October 31st. To put that attendance in perspective, consider that the Laramie Main Street Alliance holds seven one-day events that attract a total of around 8,250 people (16).

Small arts venues can have some meaningful benefits for their communities, though their economic impacts in terms of bringing in more dollars to the downtown district are relatively small. Some may be vanity expressions of a local resident, while others may have significant community impacts by celebrating a local scenic feature, historic local event or a famous local resident that is important to the community’s pride and cohesion. They also can fill vacant downtown spaces and add variety to the district’s store mix. However, their economic impacts still are likely to be negligible. Their budgets are too low and their customer magnetism just too weak for them to have significant direct and indirect economic impacts. Moreover, the small number of merchants in these downtowns also means that there are fewer that can be impacted positively by the arts activities.

It hard to say what the budget threshold is that has to be exceeded for arts organizations to have significant economic impacts. However, bigger budgets certainly increase the potential for having stronger and better arts “products” – e.g., performances, exhibitions, items created by artisans, etc. — and they can have more significant economic impacts.

The Quality of the Arts “Product” and Its “Packaging” Really Matter.

A Strong Cautionary Note: Do Not Allow Attention to Arts Buildings Dwarf Proper Attention to the Programs and Events That Will Occur Within Them. Since the early 1980s, I have come across several projects to either build or restore an existing theater or PAC. All of the completed buildings were physically attractive. However, a good number struggled financially after they opened because they were not attracting the audiences their advocates had said would appear. While enormous efforts were made to properly design and fund the building or renovation project, too often insufficient attention was paid to what would happen once the venue opened to the public. Their creators had not properly thought through what their product was, which market segments they would be sold to, how they would be marketed or how much money and personnel would be needed to do all of this. Sometimes those managing the new venues had little or nor prior appropriate professional experience.

Many of these projects were sold as bastions of the Arts, with a capital A, carrying the implication that they would be venues for performances of classy “highbrow” arts such as operas, ballets, and symphonic music. They soon found out, the hard way, that it was popular entertainment acts that paid the bills, not high culture arts performances. Furthermore, expectations about the types of acts that could be attracted were doused when board members and novice managers learned that their facility was too small to generate the revenues needed to pay the entertainers they wanted on their stages. Yes, they could have the occasional concert pianist, chamber music ensemble, dance group, touring Broadway play or even plays performed by local drama groups, but it has been the performances by pop singers, salsa bands, rap groups, rock bands, screened broadcasts of NFL games, classic films and comedians that paid the bills.

The folks at the Paramount Theater in Rutland, VT, have been wonderfully frank about their initial problems after a major renovation that enabled the theater to reopen after decades of darkness. That frankness is probably enabled because, after a few years of struggling and an important management change, the theater finally got on track by finding the right programming and pricing. Learning about the local market was critical. Eric Mallette, the programming director of the Paramount, says: “that he pays a lot of attention to what the local market responds to and tries to book shows and adjust ticket costs to fit those trends.” For many years that meant popular music and family entertainment, including the booking of a lot of comedians. According to Bruce Bouchard, who runs the Paramount Theater: “We started booking comedians and it just took off.”

What a Strong Arts Product Can Do for Arts Venues in Smaller Towns. The importance and power of the products that arts venues offer is perhaps best demonstrated by some venues I have visited that have substantial budgets, strong regional or national reputations and draw a significant number of patrons from relatively large market areas — even though they are located in small and medium sized towns. Below are four examples.

The Norman Rockwell Museum. Stockbridge, MA, is a very small town, with a population around 1,700 people. It has a wonderful old building stock, including a famous old hotel and inn. Located on Route 7, it has long been a significant tourist destination in the Berkshire Mountains. The famed artist/illustrator Norman Rockwell lived there. Local residents were models in many of his paintings. The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge is the primary repository for the artist’s paintings.

For decades his paintings were the covers of well-known national magazines. Most of his work presented an idealized version of small town, Main Street America and was very patriotic. The museum, from its inception, had name recognition and was able to build upon Rockwell’s national fame and popularity.

It has a substantial annual budget of about $4.3 million, though that is well below the average of about $8 million for art museums nationally that have annual incomes above $50,000. About 28% of its revenue comes from contributions and 52% from program services. The museum attracts around 125,000 visitors a year – about average nationally for an art museum — mostly from NY and New England, as well as another 200,000 to its traveling exhibitions. It is professionally operated with 27 full time employees, 38 part-timers, and 30 volunteers.

This museum has gravitas: lots of a high-quality arts products (i.e., many Rockwell paintings) that are packaged in a charming town in the attractive Berkshires. The area attracts many well to do second home owners and even day-trippers from the heavily populated Northeast Corridor. Its budget and visitor appeal infuse this museum with the potential to have meaningful economic impacts even though it is located in a small community. How much of those benefits go to Stockbridge and its charming Main Street and how much goes elsewhere in its region is another issue.

Brandywine River Museum of Art. It is located in Chadds Ford, PA, population 3,640. The township is about 40 miles from Philadelphia in a scenic river valley, where the DuPont family has had a big influence. The township’s population is affluent, with the median household income being $117,961 and the mean $165,971.

Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, PA

Its core attractions are Andrew Wyeth’s studio and a very large collection of his paintings. Wyeth is also one of America’s best-known artists. His painting, Christina’s World, achieved almost iconic status nationally. The museum attracts 200,000 visitors annually, double that of the average art museum. Wyeth’s fame and popularity are enormous marketing assets for the museum. Its annual revenues are relatively very substantial, around $24.6 million. That’s about three times the average art museum in the USA. It has 164 employees. Its total assets are valued at a relatively hefty $156.7 million. The museum’s operational strategy is unique since most of its annual revenues come from asset sales — probably the sales of Wyeth lithographs and paintings for which there is still a big demand.

One gets the impression that the management of this museum is trying to run it as a business as much as is possible. Its revenues, employment, and visitation indicate that it has considerable potential to exert positive economic impacts, within its county, though where and who within it would benefit are other issues.

Goodspeed Musicals. This organization is famed nationally for developing musicals, with many of its productions going on to stages in New York City and London, e.g., Annie. It owns and operates an impressive cluster of artistic facilities located in East Haddam, CT, population 9,126. The town has a median household income of $82,117 and a mean of $103,376. The town is on the scenic Connecticut River and has many historic buildings. The Goodspeed Musical’s facilities include:

- The Goodspeed Opera House

- The Terris Theatre

- Artists Village

- The Chauncey Stillman Production Facility

- Larry A. McMillian Rehearsal Studios

- The Alice Rehearsal Studios Barrington Costume Center

- The Factory Building (17).

At the functional core of this cluster is the historic Goodspeed. Built in 1876, after a long period of decline, it was restored and reopened in 1963. Attendance at the Goodspeed for 2014 was about average for an American nonprofit theater company: 105,368 patrons at 297 performances. About 26% of its revenues are from contributions, about 57% program services. Its total revenues in 2014 were an above average $13,159,845, while expenses were relatively robust at $11,708,637.

The Artists Village is an interesting and relatively recent addition. It is within walking distance of the Goodspeed Opera House and includes 17 new and five older homes. All have three or six bedrooms, with shared kitchens and living rooms. The new houses were designed specifically with artists in mind: “every bedroom has a private bathroom, extra insulation was added between walls to ensure quiet rooms, and large common areas were provided to encourage camaraderie and a sense of community” (18). The project cost for the Artists Village was $5.5 million, with $2.5 million provided by a grant from the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development, and the rest from private donors.

Weston Playhouse Theater. The Playhouse is located in a very attractive building in Weston, VT, population 566, one of the most charming villages in the state. A running stream and the town green abut the theater. Route 100, one of the state’s most scenic highways, runs through the town. Also located in the town is the very popular Vermont Country Store that literally draws busloads of tourists. Weston’s median household income is $62,500, the mean is $100,796. The area surrounding Weston attracts lots of second homeowners because of its famed scenery and nearby ski resorts, such as Okemo. The Town of Ludlow, population around 1,900, is about a 15-minute drive from Weston and close to Okemo. It has had a notable downtown revitalization in recent years, driven by an attractive cluster of restaurants and bars.

The Weston Playhouse Theater

The Playhouse is Vermont’s longest running professional theater, though it only operates for about 10 weeks during the summer months. While it does the classics, it also prides itself on nurturing new plays. Its total revenues in 2014 were an above average $2.45 million. An astonishing 63.4% came from contributions, only about 29% from ticket sales. Its annual expenditures in 2014 were $1,835,630. Its annual attendance, based on just a summer stock type operating season, is above average at about 20,000. However, its operating expenditure per visitor is quite high, $91.78, and most of it cannot be covered by ticket sales. This has placed it in potential financial jeopardy.

The Playhouse has a bar and restaurant inside, probably because there are so few other eating and drinking places in this very small town or even further out in this very rural area.

I have been following the Playhouse and visiting Weston since the early 1990s. To my ken, during that time, it has had two significant bouts with financial stress. The most recent occurred a few years ago and was probably due to the impacts of the Great Recession on donors combined with the Playhouse’s strong dependency on contributed income.

The people in the Playhouse company appear to live and work most of the year in big cities in the northeast, where they are theater professionals and/or academics. Perhaps they also have second homes in or near Weston. In many respects, what they have done reminds me of the Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney films where someone says: “ let’s put on a show” and they do. The folks that run the Playhouse company want to put on their kind of plays in Weston, a town they obviously like, during the summer, when they are more likely to have available time. They largely have been willing and able to do the hard work of attracting a substantial amount of contributions. I suspect that a lot, if not most, of those contributions, come from outside Weston’s region. If the picture I just painted is correct, then the very small town of Weston has a well-known theater because it has been able to attract a group of outside theater professionals who then have been able to attract a good deal of outside money. To my mind, that’s like Weston filling an inside straight. It’s a wonderful story, but a model that is very hard to emulate.

The Playhouse probably does not have much potential to have favorable impacts on other Weston businesses, because there just are not that many of them and it is only open for about 10 weeks a year. On the other hand, the Vermont General Store is so strong that anything the Playhouse could add to it probably would be like chump change. The most likely potentially positive economic impacts are probably felt at a county or regional level – in Ludlow, for example — and probably more on residential property values than business revenues.

Some Hypotheses About the Characteristics of Arts Venues in Small- and Medium-Sized Towns That Are More Likely to Be Successful and Have a Strongly Appealing Arts Product. Based on my research and field visits, I have generated the following hypotheses:

- Their arts product, while reflecting strong local roots, also appeals to many people outside the local area. They attract tourists.

- Their arts product is packaged in an attractive building that is located in a very attractive town that often is in a very attractive region.

- These successful venues usually do not create the tourist traffic but take advantage of, and then help grow existing traffic.

- Their towns have significant numbers of solidly middle income and/or affluent households, their percentages often greatest in the towns with the smaller populations.

- The arts venues are professionally managed and their board members are knowledgeable about the art form the organization is engaged in.

- The venues have significant budgets. (This not to say that they are always safely in the black financially.)

- The venues have leaders and managers with strong working connections, one way or another, to the arts community outside of their local areas. Such networks of personal connections are valuable for accessing talent, fund-raising, earning income and marketing. Many have come to the area as tourists, second home owners or as visitors to friends and family who are residents. That means that tourism, once it reaches a certain level, can simulate local arts projects by bringing in people who work in the arts. I think such links are far more important than is commonly realized.

ENDNOTES

1) See, for example: N. David Milder. “The New Normal’s Challenges to Developing a Downtown Entertainment Niche Based on Formal Entertainments: Part 1.” March 9, 2014 https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/03/the-new-normals-challenges-to-developing-a-downtown-entertainment-niche-based-on-formal-entertainments-part-1 and N. David Milder. “Based on Formal Entertainments: Part 2 the audiences; revised 041214.” March 28, 2014 https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/03/the-new-normals-challenges-to-developing-a-downtown-entertainment-niche-based-on-formal-entertainments-part-2-the-audiences N. David Milder. “Downtown Formal Entertainment Venues: Part 3.” April 24, 2014. Revised April 26, 2014. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/04/downtown-formal-entertainment-venues-part-3 N. David Milder. “Downtown Formal Entertainment Venues Part 4: Movie Theaters.” May 25, 2014 https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/05/downtown-formal-entertainment-venues-part-4-movie-theaters

2) Roland J. Kushner and Randy Cohen. National Arts Index 2016, p.2; Americans for the Arts. http://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/2016%20NAI%20%20Final%20Report%20%202-23-16.pdf

They did not look at arts organizations with annual revenues under $50,000 so their finding that larger arts organizations are more prone to having deficits should be treated with caution. The 2016 version of the NAI will be its last and that is a real shame. It has been a treasure of data that arts organizations should use not only for advocacy, but also for planning their budgets and programs.

3) See: http://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/ArtsFacts_ArtsOrganizationRevenues2014.pdf

4) NEA. “How the United States Funds the Arts.” 2012. P 1. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/how-the-us-funds-the-arts.pdf

5) Lisa M. Sontag-Padilla, Lynette Staplefoote and Kristy Gonzalez Morganti. RESEARCH REPORT. Financial Sustainability for Nonprofit Organizations: A Review of the Literature. Rand Corporation, 2012. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR100/RR121/RAND_RR121.pdf

6) Data on the revenues and expenditures of the specific arts organizations described in this article come from the Form 990 filed with the IRS and available from online sources.

7) Randy Cohen. “What’s Measured Matters . . . Private Giving to Arts &

Culture: Way Up in 2014.” ARTSBLOG, July 10, 2015. http://blog.americansforthearts.org/2015/07/10/what%E2%80%99s-measured-matters-private-giving-to-arts-culture-way-up-in-2014

8) Ibid.

9) Giving USA. “Data Tables for Charts in The Numbers

Giving by source, 1976–2016.”

10) See endnote 2, p.24

11) The Conference Board. “TCB Giving Numbers 2016.” https://www.conference-board.org/publications/publicationdetail.cfm?publicationid=7297¢erId=1

12) See Endnote 2

13) Ryan Stubbs, “Public Funding for the Arts: 2014 Update.” GIA Reader

Vol. 25 No. 3, Fall 2014 http://www.giarts.org/article/public-funding-arts-2014-update

14) Andy Horwitz, “Who Should Pay for the Arts in America?” The Atlantic, Jan 31, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/01/the-state-of-public-funding-for-the-arts-in-america/424056/

15) Zannie Voss and Glenn B. Voss, “Arts and Culture Are Closer Than You Realize: U.S. Nonprofit Arts and Cultural Organizations Are a Big Part of Community Life, Economy, and Employment —and Federal Funding Enhances the Impact.” National Center for Arts Research, SMU. Pp.7. https://sites.smu.edu/Meadows/NCARPaperonNationalArtsandCultural%20Field_FINAL.PDF

16) Information kindly provided by Trey Sherwood, Executive Director of the Main Street Alliance in 2016.

17) Information about these facilities was obtained from the Goodspeed Musicals website: http://www.goodspeed.org/?gclid=CJ7Tqp6sxdQCFYaPswodusULkQ

18) See the Artist Village pages on Goodspeed’s website.

UP NEXT IN PART 2 OF THIS ARTICLE

Part 2 of this article will focus on the changing characteristics of our population’s participation in the arts and the impacts of the arts on downtowns. Failure to understand the altered arts participation landscape is leading to bad project and program choices by arts organizations. Failure to understand the impacts the arts really have on our downtowns has led to some very disappointing results for downtown leaders and stakeholders who worked hard to bring arts projects to their districts.

* The Forthcoming “Let’s Get Real About…” Series of Articles.

My recent article on pedestrian activity concludes the large number of articles I’ve done on the New Normal for Downtowns that I have been working on since 2008. I will, of course, again return at times to that topic in the future, but I also want to write about many other subjects. At this moment, that means describing and trying to spark debate about a number of subjects I believe are being mishandled by downtown revitalization leaders and experts because either unproven assumptions are being made or the subject is simply not being properly understood. This will be done in a new series of articles that I have dubbed “Let’s Get Real About…”. I have already taken on one of these subjects in my articles about leakage analyses. Above, is the first article in that series. It details the challenges presented by trying to use the arts as a key downtown revitalization tool. Other topics I plan to address in future articles, though not in the order in which I probably will take them on, include:

- Are lots of people strolling, window-shopping and browsing in stores what makes downtown retailers successful? I already broached this subject with some detail in my pedestrian activity article, but I want to do a deeper dive on this subject because I think this behavior pattern holds such a pivotal position in our conventional wisdom about how downtowns work.

- Are the uses of best practices/success stories usually beneficial?

- Are small businesses always revitalization assets — and big businesses bad for the small ones as well the community at large?

- Are new retail spaces not needed because the market is already glutted?

- Eyes on the street: is that what really makes people feel safe?

- Are most downtown retail market analyses on the mark?

- How the Internet is eroding the legendary importance of location, location, location.

I welcome suggestions about other topics and articles from other authors on them.