By N. David Milder

Introduction

Over the past 15 to 20 years, pedestrian activity has become an essential element in our understanding of how successful downtowns and Main Street districts work. Such activity has qualitative and quantitative aspects. The well deserved and growing attention that downtown “walkability” has garnered reflects the qualitative concerns of those active in downtown revitalization about the physical and social conditions that encourage pedestrian activity. It is also a de facto acknowledgement of the importance of such activity. However, in my opinion, a lot of important issues are being generated by pedestrian activity that are not being acknowledged, much less being resolved. They could benefit from conceptually and methodologically rigorous quantitative analyses. Moreover, such analyses needs to look at not just pedestrian activity in isolation, but also how it relates to other economic and social behaviors and attitudes. In this article, I’ll take a stab at outlining some of these issues.

How Much Pedestrian Activity Should Your Downtown Have?

It might be reasonably argued that this is one of the most basic questions that should be addressed by any downtown revitalization plan or strategy. Below are some observations and ruminations about pedestrian flows I’ve been accumulating over several years. They stimulated me to look more closely into this question and to realize how complex the task of answering it might be.

The Importance of the Quality of the Pedestrian’s Experience. Many years ago, before the NYPD instituted corrals for the event, I took my nine-year old daughter to Times Square on New Years Eve. It was a ghastly mistake! A strong surge in the crowd sent people flying into us and my daughter went to the ground. I thankfully was able to get her in my arms before she was trampled by the crowd. Lesson learned: a lot of people close together on foot can be very, very dangerous. At what point does pedestrian density become dangerous? Is there some metric about how much space a pedestrian needs to be safe and to feel comfortable and unstressed?

I have long avoided many streets in Midtown Manhattan at certain times of the day, e.g., lunchtimes and during the evening rush, and especially at certain times of the year, e.g., most of December and St Patrick’s Day, because the sidewalks are so crowded, sometimes also with raucous people, that:

- I have to walk in the street and then take care that I’m not run over by passing vehicles or

- Staying on sidewalks, I strongly fear bumping into other people or being bumped into far more often than I’d like by unpleasant people. Walking then becomes a very labored, fearful and thoroughly unpleasant experience. Lesson learned: overly crowded pedestrian traffic is inducing me to dislike walking in these areas so I avoid them, much as New Yorkers avoided Bryant Park back when it was known as a crime ridden and dangerous place. I suspect I am far from alone in having this reaction. As Yogi Berra famously said, “no one goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

How many downtowns are inducing avoidance behavior and having their images tarnished by too much pedestrian traffic congestion? My suspicion is that it is happening far more often than their leaders and stakeholders either realize or would want. In turn, this raises the question of at what point does the density of pedestrians begin to significantly make walking an irritating, joyless labor and an inducement for avoidance behavior? How much pedestrian traffic is too much pedestrian traffic?

A headline in a 2016 article in the New York Times blared: “New York’s Sidewalks Are So Packed, Pedestrians Are Taking to the Streets.” (1) Such behavior is a good indicator of a malfunctioning pedestrian environment, but it is not a good measure of the extent of the underlying problem. Many, many other pedestrians are staying on the sidewalks, but are far from happy about the situation they are in.

While this happening in Manhattan on 5th Avenue in and near Rockefeller Center, in the Times Square Bowtie, along Broadway and elsewhere in Lower Manhattan, around Macy’s and near Penn Station is perhaps to be expected, I have been in similar pedestrian traffic jams, though less frequently, on the sidewalks of: Austin Street in Forest Hills, NY; Main Street in Flushing, NY, Jamaica Avenue in Queens; Fordham Road in The Bronx, Main Street in East Hampton, NY, Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Newberry Street in Boston and Ocean Drive in Miami Beach.

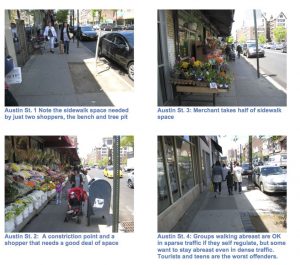

Impediments to a Good Pedestrian Experience. In many of these pedestrian traffic jams, walking is being constricted by such things as narrow sidewalks, stores bringing their merchandise stands out on the sidewalk, outdoor restaurant seating, newsstands, street and truck vendors and their customer crowds, street performers, street tree pits, planters, benches, construction sites, bus shelters and normal window shoppers. In too many instances, the possible pedestrian path on the sidewalk is only wide enough for one person. Lessons learned:

- When these issues are not properly addressed they can make walking so difficult and unpleasant that they negatively impact a district’s image and increase avoidance of important portions of it.

- Even very desirable amenities, e.g., street trees, planters, benches and bus shelters can cause problems simply because of the amount of sidewalk space they occupy. (See the Austin Street photos below). Also, shoppers with shopping bags, shopping carts and children in strollers/carriages will need more space than the average pedestrian. Americans are also getting more obese and consequently occupy a larger volume of space. Smaller communities certainly are not exempt from having such problems.

Downtowns that want to attract more pedestrians need to take these factors into consideration. Just setting the attraction of more pedestrians as a goal is acting with blinders on. As the astute Andy Manshel recently emailed me: “Our work is always all about balance.”

Austin Street in Forest Hills, NY (and in NYC) is a very strong and popular shopping corridor. It suffers from narrow sidewalks, sometimes even when pedestrian flows are relatively sparse. That problem rises to the point of being very detrimental during late afternoon and weekend pedestrian peaks.

Rules for the Sidewalk? Certain pedestrian behaviors, those that might be called pedestrian incivilities, too often also impede the smooth flow of pedestrians and make walking thoroughly unpleasant. Some of these incivilities are: raucous, drunken behaviors; walking against the flow of traffic; walking in groups of three or more lined up across the sidewalk; aggressive passing; stopping and standing in the middle of the sidewalk, especially in groups. Lessons learned:

- There may be rules of the road for drivers, but apparently, there are no behavioral rules of the sidewalk for pedestrians.

- There is a need for an accepted etiquette of pedestrian behavior, but its codification and acceptance will probably be very, very hard to accomplish. How could it be accomplished and by whom?

- Pedestrian flows, I’ve been told by experts, are self-regulating. Who or what steps in when that self-regulation fails to work properly? Incivilities are good examples of such failures.

- Individuals can find that self-regulation can become a very negative experience, full of uncertainties and possibly fears. It also can require a lot of hard work.

- My observations suggest that tourists are more prone than New York residents to engage in pedestrian incivilities, though local teenagers are also frequent miscreants. If this is the case, how do the tourists impact on our ability to remediate this problem?

- Districts with high levels of pedestrian incivilities should not try to develop levels of pedestrian traffic that increase the frequency and adverse consequences of such incivilities.

Pedestrian Traffic in Small Towns. Small and medium-sized downtowns will never have the consistently strong pedestrian flows found in our big, traditionally urban cities such as NYC, Chicago and Boston. (See the table below.) They just do not have the needed large daytime populations and the development densities that generate them. So, how much pedestrian traffic should they have? And how can that be determined? By their land use densities? By the needs of local merchants and those targeted for recruitment? By sidewalk capacities? By the number required for the district’s sidewalks to look active and interesting? Or are they so small that such a concern is simply irrelevant for them?

Who You Add Really Counts! Among the relatively smaller downtowns, I have come across some instances where local leaders have complained that their events have drawn either more people than they could handle properly or the kinds of folks they did not want (e.g., bikers, hot rodders, aggressive panhandlers, drug dealers). In several other small and medium-sized downtowns both merchants and residents have complained that a recent big influx of tourist traffic has changed the basic character of their district for the worse. Lesson learned: the composition of the increased pedestrian traffic can really matter; another reason more pedestrian traffic may not always be beneficial.

Pedestrian Traffic as a Locational Asset. Conventional wisdom has long held that strong pedestrian traffic should be one of a downtown’s most valuable locational assets. However, I have not been able to find any research supported metric that shows with any accuracy how many pedestrians passing by a location are needed to support any kind of retail, food or entertainment operation. Questions:

- How is a retailer to know if the pedestrian count near a potential new location is a really sufficient for its store to prosper there? Apparently, from their sales records, many retail chains do know, though in fairly broad terms, that their stores do better in locations with relatively high pedestrian counts. Yet, there is no evidence that they know of a threshold of pedestrian activity that has to be exceeded, much less how many passing pedestrians are needed to support a square foot of leased space or $1,000 of store sales.

- How, then, is a downtown EDO to determine what level of pedestrian activity its prime retail-prone spaces need to attract and sustain desired retail tenants?

My recent look at the 34th Street District had an admittedly small sample to study, but it did indicate that some of the district’s most desirable retailers probably valued being closer to other retailers of similar caliber more than proximity to larger pedestrian flows (2). Question: how important is pedestrian traffic in retail locational decisions compared to other factors? Which other retailers are nearby, the characteristics of available spaces, including their size, rent and lease terms, may be more important.

One of the unexplored and untested gospels about healthy downtowns is the pedestrian strolling, window-shopping and browsing scenario for retail success. According to this lore, downtowns are healthy and retailers successful when downtown visitors can leisurely stroll along its sidewalks, window-shop and then browse inside the shops. It is one of the reasons why downtown retail locations are supposedly advantageous. However, today, this scenario often breaks down:

- In many smaller downtowns and Main Streets, there just are not enough shops to warrant much strolling and the shops are not apt to change their merchandise frequently enough to warrant much window shopping or browsing. My field experiences in such towns suggest that store visits are overwhelmingly need driven to merchants that are locally well known and these merchants are identified destinations before the shopping trips are initiated. Question: In these downtowns/Main Streets, can more resident-driven pedestrian traffic really make all that much difference for retailers?

- In really big downtowns with very high pedestrian traffic, it is sometimes hard to window shop because of frictions with passing pedestrians. At what level does high pedestrian traffic begin to significantly discourage window-shopping?

- Today, before Americans go on a shopping trip, they overwhelmingly search on the Internet for the merchandise they want and the shops where it is sold. Consequently, the related residential shopping trips are now much more destination generated, less the result of strolling, browsing and exploring. With tourists, strolling and window-shopping behaviors are probably still significant. However, it may be asked if a lot of pedestrian traffic is still really an important factor for the retailers that are mainly attracting Internet-driven destination shoppers? The Internet is eroding what location, location, location has meant in our downtowns.

Is Simply More Really Better? In decades past, when downtowns were in decline or just starting to revive, getting higher levels of pedestrian traffic was a highly desired objective, even when there was little hope of achieving it. In more recent years, almost every downtown and Main Street revitalization strategy or plan I’ve seen has echoed this “more pedestrian activity is better” theme. Some of them, I wrote. One of my strongest arguments above has been that more is better only if a good pedestrian experience can be maintained or created. Many more of these revitalization plans and strategies should have addressed this issue of the quality of the pedestrian experience they provide – including some of mine. The objective downtown EDO’s should really adopt is attracting more visitors who will be happy because they so enjoyed walking on your downtown’s sidewalks and in its public spaces. I am even tempted to say that should be The First Commandment of Downtown Revitalization.

A Quick Look at the Times Square Bowtie

A brief look at Times Square is worthwhile because it demonstrates so forcefully a number of the points I have argued above.

One of the most salient features of the new normal for our downtowns is that while being successful, they must face a range of relatively new problems. Nowhere is this more forcefully demonstrated than in Times Square, where very high pedestrian flows have been a growth and business recruitment asset as well as the cause of overcrowded sidewalks, frequently unhappy pedestrian experiences and possibly a disincentive for business attraction and retention.

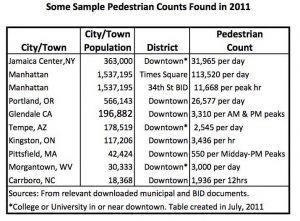

The behavior of the Times Square Alliance (TSA) also demonstrates how important the collection of data on pedestrian traffic has become for some downtown district management organizations. In 2012, the TSA completed the installation of an automated counting system that “provides 24/7/365 data on the number of pedestrians who enter and pass through specific counting zones of the Times Square Bowtie (7th and Broadway between 42nd and 47th).” (3)

It’s Economic Rebirth. This world famous urban area, especially in the “Bowtie,” has experienced an enormous and impressive rebirth. In the latter part of the 20th Century, despite its large cluster of legitimate “Broadway” theaters, the many show-goers they brought in, and the hordes of tourists attracted by its signage and honky-tonk atmosphere, Times Square increasingly was known as a decaying place filled with of all sorts of porn establishments, lots of homeless and prostitutes and a high level of criminal activity. Today, that blight and most of the deviant behavior has disappeared – to the point that a few mavens long for some of its former edgy, honky tonk atmosphere to return. The area has attracted new office buildings with major corporate tenants and hotels. Major retail chains have opened, including: Loft, Forever 21, Gap, H&M, Uniqlo, Levi’s, American Eagle, Charles Tyrwhitt. The theaters have had record box office numbers in recent years. Overall, today, Times Square is a stronger than ever attraction for tourists.

Its retail rents are an important indicator of its resurgence and desirability as a retail location. In 2016, average asking rents in the Bowtie were $2,170 PSF, the second highest among all of Manhattan’s major retail corridors. Moreover, these rents grew by 150% between 2008 and 2016, the largest increase among those retail corridors. (4)

An Astonishing Level of Pedestrian Activity. The TSA’s counts for March 2017 showed that:

- Over 300,000 pedestrians enter the Times Square Bowtie each day. That is equivalent to being the 64th largest city in the USA by population.

- On the busiest days, Times Square pedestrian counts are as high as 480,000. That is equivalent to being the 35th largest city in the USA.

- Times Square stays active in the evening: 66,000+ pedestrians enter the “Bowtie” between 7 pm and 1 am. (5)

Only a handful of commercial districts worldwide can rival these numbers.

The map below shows the March 2017 pedestrian counts broken down by the nine sidewalk and five plaza locations where they were observed. Within the core Bowtie area are six of the sidewalk locations and all five plazas. The plazas are more like public spaces, with places for people to sit and stay. They averaged 93,866 visitors per day, with a high of 158,739 and a low of 72,266. The average sidewalk counts in the Bowtie, that look at the more constantly moving pedestrians in smaller spaces, was about 30% lower than that of the plazas, 66,020, but still impressively strong. The sidewalk counts ranged from a high of 78,810 to a low of 48,608.

Times Square 1: Map from the Times Square Alliance shows pedestrian counts in March 2017 at different locations.

These High Levels of Pedestrian Traffic Are Not Problem Free. By the early 2000s, because of the negative experiences generated by Times Square’s very heavy pedestrian traffic, I and many, many other New Yorkers, avoided walking in the area as much as possible, only doing so when going to important business appointments or shows at one of its many theaters. The sidewalks were so packed that walking in the area was thoroughly unpleasant and too often irritating. A good tell of this was the fact that more and more people were leaving the sidewalks and taking to the streets. A TSA pedestrian count in 2006, for example, found that as many as 9,148 pedestrians a day were walking in the street on Broadway between 46th and 47th Streets despite high levels of vehicle traffic (6). It seems reasonable to assume that many of them felt it was safer, easier and/or faster to walk among the vehicles than in the dense flow of pedestrians!

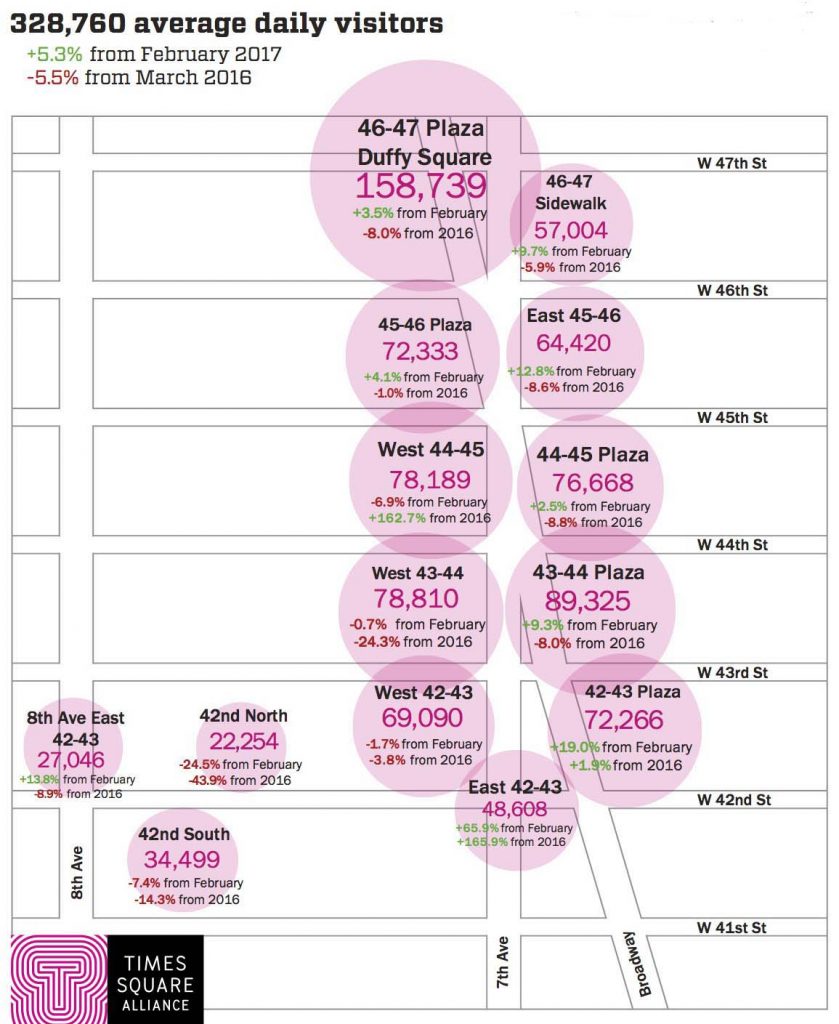

A Very Gutsy Project to Rebalance the Situation. Broadway is an old and long street that predates Manhattan’s street grid and runs 13 miles through Manhattan, two miles through The Bronx and 18 miles through towns in Westchester. Because it cut diagonally across so many important north-south avenues it caused a lot of vehicular congestion. Its sidewalks in the Times Square Bowtie were also badly overcrowded. Around 2008, the Bloomberg Administration decided to take a very bold move on Broadway below Columbus Circle that basically banned it for vehicles or made it very unfriendly for drivers. At least half of its traffic lanes were closed and repurposed for bike riders and pedestrians. Between 33rd and 35th Streets near Herald Square and in the Times Square Bowtie between 42nd and 47th Streets, Broadway was completely closed to vehicle use. The resulting freed space in the Bowtie was used for more sidewalk space for pedestrians and for plazas with street furniture that visitors could use. (See photos above Times Square 2-4)These renovations took about six years to complete, finally concluding just before New Years Eve in 2016. They reportedly added about 100,000 SF of pedestrian space that reduced pedestrian congestion and added 50% more space for events and concessions (8). Reportedly, 65% of NYC residents felt the plazas made the experience of being in Times Square better. Pedestrian traffic in the street bed also was said to have been reduced, even while overall pedestrian traffic reportedly increased.

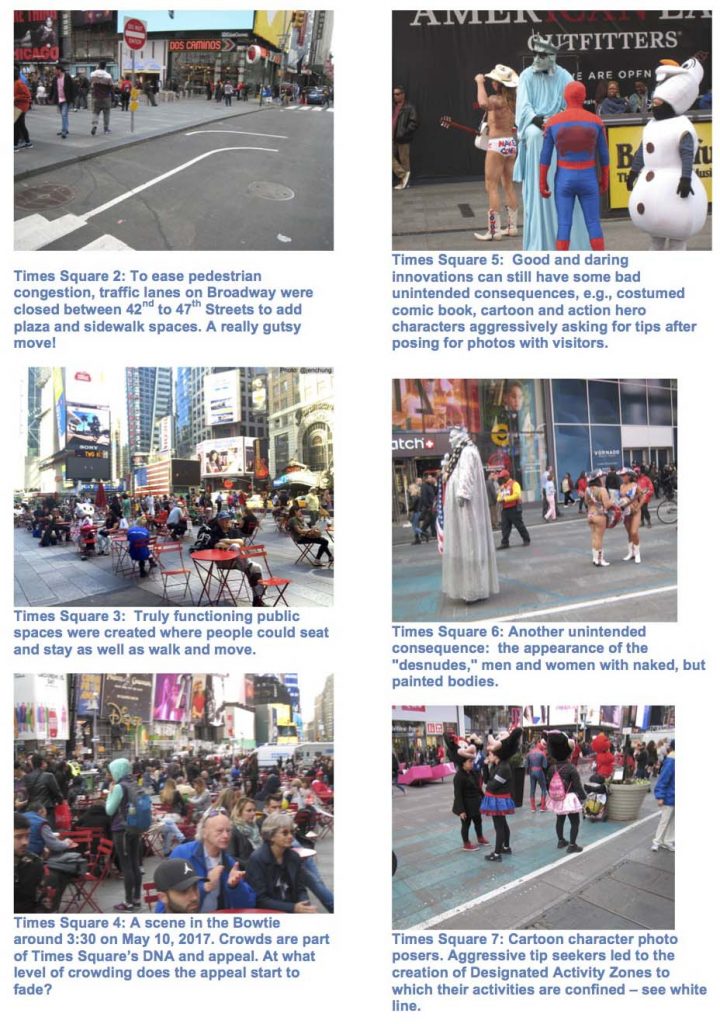

New “Old” Problems Emerged. Unintended consequences are perhaps the devil of downtown revitalization — they certainly bedeviled Times Square’s new plazas. Before the area’s revival, it was known for its porn-oriented businesses. They left, but around 2002 the Nude Cowboy (who was not completely nude) appeared, who sang and posed for photos for tips. Over the years, especially after the creation of the plazas, other buskers came in along with cartoon, comic book and action hero costumed people who posed for photos with visitors for tips. They were joined by the “desnudas,” women who were nude, but had costumes painted on them. (See photos Times Square 5-7). By 2015, as the numbers of these tip seekers increased and as complaints rose about their nudity and aggressive, perhaps illegal, treatment of visitors rose to a crescendo, a significant political movement emerged to tear up the plazas. The NYPD seemed to be in the lead. Noted urbanists, such as Jan Gehl, rushed to the plazas defense, arguing that better stewardship could keep them both vibrant and orderly.

One outcome was the creation within the plazas of Designated Activity Zones to which the tip seekers were confined. You can see the white boundary line of one of these zones in photos Times Square 6 and 7. I have not seen any study of the zone’s impacts. My own field observations on three visits over the last year are that the behavior of the tip seekers has become less aggressive or problematic. My hunch is that a lot of them know that if their behavior again becomes an issue, then they will soon be gone.

Impact On Business Recruitment and Retention. In a lot of ways, the somewhat edgy behavior of the tip seekers is consistent with Times Square’s edgy honky-tonk behavior of decades past. Furthermore, one might reasonably argue that, today, edginess along with its humongous colorful signs and dense crowds remain as fundamental pillars to the area’s image and attractiveness to tourists. But, how consistent are they with the needs of local business recruitment and retention efforts?

Around the time, in 2015, when the plazas were being called into question, an article appeared in the New York Times that was titled “Times Square’s Crushing Success Raises Questions About Its Future.” (9) The article asks: “With all this going for it, why are so many landlords, office tenants and theater owners worried about the future of Times Square?” Its answer is very noteworthy because it was made well after steps had been taken to significantly reduce pedestrian congestion in the area: “The same reason that retailers and advertisers lust after a Times Square location is the same reason that others now find it unbearable: the crowds.” (The emphasis added is mine).

Office workers were said to complain about navigating “thick and sometimes unyielding knots of tourists in various hot spots.” Some business people said the area was too congested for New Yorkers to do business. Office workers found it hard to get lunch in restaurants so crowded with tourists. Major corporate tenants were trying to solve crowded streets problem by opening cafeterias and gyms within their office buildings. Others had their executives conduct business east of the district.

A lawyer in a large white shoe law firm that left Times Square noted: “Everyone agreed, it’s awful there. People would go well out of their way to avoid Times Square.” (10)

Also noteworthy is the fact that local businesses that basically deal with the tourists, i.e., those in the hospitality and retail sectors, are not negatively impacted by the crowding.

The Impacts of the Plazas. The plazas have increased pedestrian traffic, but whether or not they have substantially improved the pedestrian experience remains unknown. My personal experiences suggest the improvements, if any, are marginal. My suspicion is that tourists are much more likely to put up with the area’s poor pedestrian experience because it is, in a sense, what they came to have and they know they do not have to endure it on any repeated basis – they can go back home. We New Yorkers, on the other hand, are usually in a rush and we will avoid the area’s congested pedestrian flows whenever and however we can.

The leaders of the TSA are pros and apparently fully aware of the situation. As one of them stated to the Times: “Our concern is that the public realm is so unpleasant that we may at some point hit a tipping point, where companies won’t take space in Times Square. We’re not there yet, but the data is telling us we could get there.” (11)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This book has had a great impact on my interest and understanding of urban pedestrian behavior: Urban Space for Pedestrians by Boris Pushkarev and Jeffrey Zupan (MIT Press 1975). My understanding is that Jeff and his RPA crew are doing an update to it. I am eager to see the results and recommend that anyone interested in downtown revitalization should be as well.

ENDNOTES

1- Winnie Hu, “New York’s Sidewalks Are So Packed, Pedestrians Are Taking to the Streets.” The New York Times. June 30, 2016. http://nyti.ms/29dy7m3

3- From the Times Square Alliance (TSA) website: http://www.timessquarenyc.org/do-business-here/market-facts/pedestrian-counts/index.aspx#.WQda-lPyvjA

4- Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) Retail Report 2016

5- From the Times Square Alliance (TSA) website: http://www.timessquarenyc.org/do-business-here/market-facts/pedestrian-counts/index.aspx#.WQda-lPyvjA

6- See: The TSA’s 2006 Summer Pedestrian Counts, Wednesday, July 16 available on its website.

7- See: http://www.timessquarenyc.org/live-work/times-square-transformation/faq/index.aspx#.WRMVWFPyvjB

8- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Times_Square

9- Charles V Bagli, “ Times Square’s Crushing Success Raises Questions About Its Future.” New York Times, Jan. 26, 2015. http://nyti.ms/1DcL5o6

10- Ibid.

11- Ibid.