By N. David Milder

Introduction

For about 10 years now, I have been advocating in my blog, presentations at conferences and recommendations to clients that vibrant parks and public spaces are more critical than ever to the success of downtowns in our smaller communities. However, more often than I’d like, I’ve had some pushback from folks who argue one or more of the following points:

- They already have a public space, and nobody uses it. It’s deader than a doornail, more of a town liability than an asset.

- They’re a small town and their market area has a small population, so their downtown does not attract a lot of visitors who might use a public space.

- Their municipalities have limited finances, so it is extremely difficult to build a new public space or to significantly improve an existing one. Insufficient financial resources also mean that it is problematic to properly maintain existing public spaces or to provide the staff needed to facilitate the use of potential attractions, e.g., ping pong tables, boules courts, etc.

This article is premised on the belief that there are solutions to all of the above problems and that by incorporating knowledge of them into the designs and management of small-town public spaces, these spaces can be turned into successful and important downtown assets.

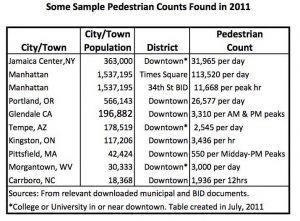

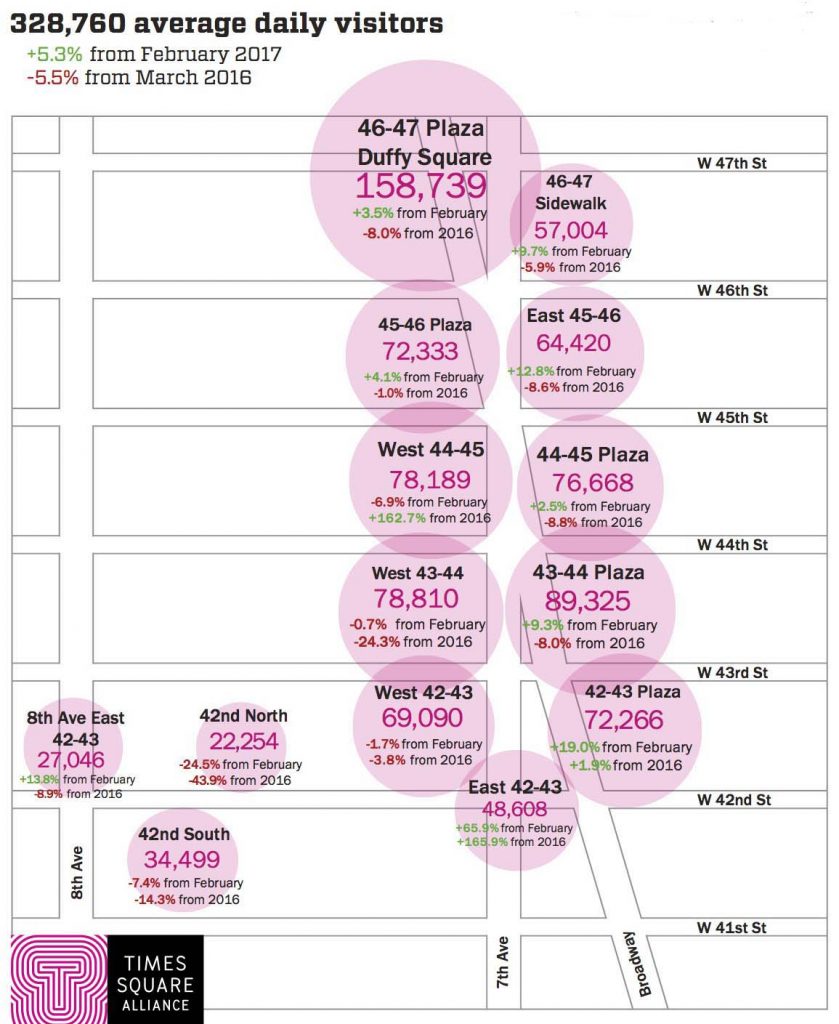

Setting Viable Aspirations for Use Levels

At the outset, it is essential to establish realistic expectations. These small-town spaces will never have the visitation levels of major urban public spaces where, for example, Bryant Park in New York can attract over six million visits annually and its neighbor, Times Square, draws over 300,000 pedestrians per day. On the other hand, if meaningfully activated, on days when they are not serving as the venues for events, the small-town parks and public spaces still can attract a significant number of visitors. Annual visitation levels for these small-town venues of 100,000+ are certainly possible and counts as high as 300,000/year have been achieved (1).

Town Green on a summer midweek afternoon, Guilford, CT

At most points in time during the weekday the small-town public spaces may have very few to no users, but this also even happens in large urban parks that still appear well activated, e.g., the Overlook section of Forest Park here in Kew Gardens, NY. However, at several times during the day — my observations suggest lunchtime, after school, and possibly 7:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. are the most likely times — a successful small-town public space can have a good chance of attracting platoons of users, some of whom are there with different subgroups, while others are alone. Altogether they may number no more than five or six people at a specific point in time, though their numbers on occasion can be substantially higher, e.g., 50 to 60.

Visitors Attract More Visitors. The presence of one small group of visitors helps attract other visitors, who may come at a later point in time. The existing visitors help validate in the eyes of passersby that the park has something worthwhile to see or do, encouraging them to visit as well. (This assumes the visitors’ behaviors are orderly).

To my knowledge, there, unfortunately, are no studies that show how many users a public space needs to project an image of being active, popular and worthy of a visit. But, my sense is that potential visitors make their own subjective judgments about visiting a park based substantially on who they see there and what they are doing.

Small town and market area sparse populations do not have to mean dead, inert and underutilized parks and public spaces if, on non-event days, those spaces attract several platoons of visitors at several times of the day.

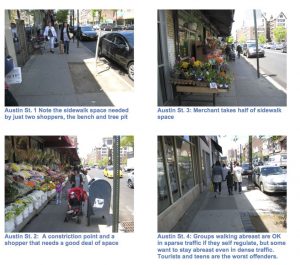

Too Often, Public Spaces in Smaller Communities Focus on Just One of Three Necessary Functions

My field observations have led me to conclude that these venues can perform three important and essential functions:

- Provide visitors with a green refuge for resting in peace and quiet.

- Provide infrastructure assets and programs that stimulate visitors to engage in activities (i.e., to “perform”), many of which also will entertain people watchers visiting the venue. Some examples of such assets are ping pong tables, boules courts, model boat ponds, “reading rooms,” carrousel rides, ice rinks, chess tables, swings, spray pads, square dances, dance contests, etc.

- To present events visitors can attend such as movies, plays, concerts, lectures, dance recitals, etc. Event attendees are almost always passive audiences (2).

The Pocket Park in downtown Washington Borough, NJ. This 4,000 SF park is the location for the town’s Farmers Market and several other events, but it has little appropriate seating or shade and no opportunities for visitors to engage in any activities. Its sole function is to serve as a location for events.

A Primary Focus on Events Limits a Public Space’s Potential Magnetism. One of the major problems of underutilized small-town public spaces is that their design and operation are focused on their being an events venue (see photo above). Such a narrow focus, of course, means that the space was probably easier to design. Operational costs are also probably minimized since the venue’s events are probably produced and funded by non-municipal organizations. Programming is offloaded. However, the number of their probable events means that the venue will be inactive on the vast majority of days in any year. For example, if the venue had a relatively robust schedule of events on fifty days, it still would have no events and be inactive on 84% of the days in a year.

The Critical Need for Appropriate Seating and Shade. Another major problem with many of the underutilized spaces is that they fail to provide the prime requisite for adequately performing the green refuge function: adequate seating and shade. If these spaces are to be sticky and keep visitors for any meaningful length of time, there must be comfortable seating for them. Tables and chairs, of course, also encourage visitors to eat their lunches and snacks in the public space. Food consumption and sale is a key to having a successful public space, no matter the size of the downtown or the community.

Too many of the small-town public spaces I’ve visited in the past 10 years lack such seating in adequately shaded areas. Even some of my favorites such as Mitchell Park in Greenport, NY and Central Park Plaza in Valparaiso, IN. (Happily, the situation in Valparaiso was corrected in the park’s second phase of development). On hot days, that can strongly discourage visits from anyone who is not a sun worshiper. What has been most surprising, is that even some well-known designers of public spaces have been among those failing to include anything approaching adequate shade in some of their project designs.

People Need Reasons to Visit Public Spaces on Non-Event Days. Those that provide infrastructure assets and programs that stimulate visitors to engage in activities give people the strongest reasons to visit. They substantially widen the variety of things visitors can do. Many of these attractions are there all day and every day, and they are not scheduled. These attractions also allow visitors to be active participants in the venue’s activities, rather than being just passive audience members. However, public spaces in smaller communities often lack such attractions. They have event programming, but not what may be called infrastructure programming. If a ping pong tables or chess tables were there, visitors might be stimulated to use them. Most often such attractions are not there reportedly because of a lack of financial resources to cover the costs of creating such attractions as well as the costs of the staff that would be needed to operate them, e.g., a carousel, an ice rink, a reading room, a bocce court. However, I suspect that the designers of these public spaces and/or the people who now manage them never considered providing such attractions and were unaware of their power and importance. Rectifying this situation may be the best way to strengthen downtown public spaces in our smaller communities.

A Good Location is Necessary, but Insufficient for Success, and, Importantly, a Location Can Be Improved

The location of a public space is extremely important for a number of reasons. Its visibility to downtown visitors drawn by its other attractions – retailers, eateries, services, government offices, entertainment venues, etc. — will influence how many visitors it will attract. Also, as Olmsted proved long ago about Central Park, and as more recent researchers have proved about other successful parks, parks can have positive impacts on real estate values on proximate properties and impact the desirability of commercial spaces. Where a park is located will determine what it can potentially impact. Far too many small and medium-sized downtowns have located public spaces where they are invisible to most downtown users and where they have a low potential for having significant positive economic impacts. Instead, they should be located, if possible, in what otherwise would be considered as worthy development sites, those that already benefit from significant flows of pedestrian and vehicle traffic and are proximate to other downtown assets.

The Center Street Alley in downtown Rutland, VT is a troubled public space because it is surrounded by buildings and has no visibility from surrounding streets.

In downtown Downers Grove, IL, Fishel Park, and Its Veterans Memorial Bandstand are not visible from Main Street.

In downtown Downers Grove, IL, Fishel Park, and Its Veterans Memorial Bandstand are not visible from Main Street.

Very importantly, a public space’s location also will determine the pool of people who are its most likely users. In urban areas that pool is most easily defined by:

- The people who live, work and study with a five-minute walk of the venue (about ¼ of a mile.

- Those who visit this area to shop or complete medical or business chores or are staying overnight in its hotels.

- Those who are walking or driving by the public space’s location.

In suburban and rural areas, whether we like it or not, the auto plays a much larger role in personal trips than walking. Based on my field observations, I would suggest that in suburban and rural small downtowns, the most likely users of their public spaces are to be found within a five-minute drive of the venue. Within that travel shed, I hypothesize that the propensity to visit the venue has the following hierarchy:

- Those who are within an easy five-minute walk, say .25 miles.

- Those with a doable ten-minute walk, say .50 miles.

- Finally, those who are more than .50 miles from the venue, but within a five-minute drive of the public space.

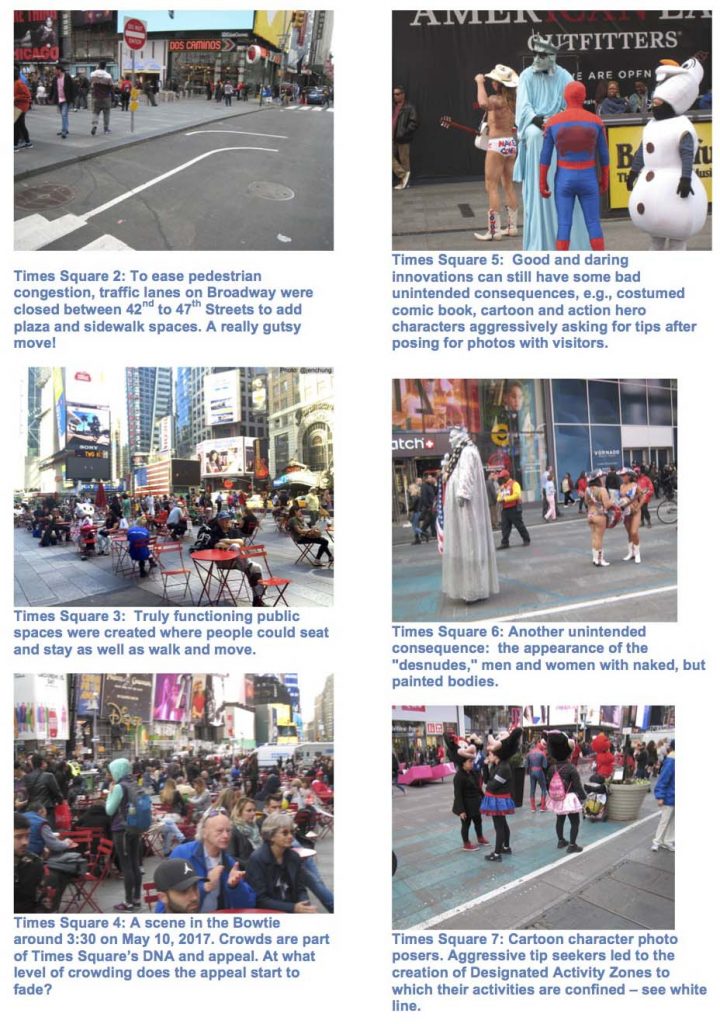

Learning from Bryant Park. This park in Manhattan has been widely acclaimed for its successful revitalization and popularity after decades of crime induced decline. Though it is located in the largest and strongest CBD in the USA, it’s history is relevant to all public spaces, be they in small rural towns or in large, dense urban areas. It demonstrates a number of very important points related to activating public spaces.

Its Location Gives It Great Visibility and Access to a Huge Pool of Potential Visitors. The blocks surrounding this park are densely filled with high rise office buildings and a large number have ground floor storefronts. Its surrounding streets are jammed with cars and buses. The park’s management estimates that, on an average weekday, about 250,000 people walk by on the sidewalks of the four streets that surround the park; a significant number are probably tourists.

About 78,000 people are employed within a 5-minute walk just from the park’s 42nd Street and Avenue of the Americas entrance. Also, there are 29 hotels within 0.2 miles of the park. Times Square is within a three-minute walk, while the Grand Central Terminal, Macy’s and Rockefeller Center are both within roughly six-minute walks. This means that the park does not have to bring people into the area and its management can completely focus on the essential task of capturing users from the vast number of people who already are in the area.

A Strong Location Provides a Pool of Essential Potential Users, but the Park’s “Products” Are What Gets Them to Actually Make Visits. Bryant Park’s strong location is what gives Bryant Park access to a very large number of potential users, but it alone could not assure its success. Consider that the flow of pedestrian traffic near the park during its troubled days was probably lower than today’s, but still relatively very strong when compared to downtown locations in other cities. What turned the tide was not the new and renovated office buildings and hotels that have appeared since 1992 — they came after the park became a success– but what was happening inside the park, the new “products” it offered and how they were “packaged.” That’s what drew all the visitors into the park and encouraged them to stay. A superb location was not enough by itself, but it is still damned important.

A Location’s Pool of Potential Users Can Be Made Larger. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, before Bryant Park entered its period of steep decline, the area surrounding it was relatively healthy and successful. The park’s decline made the leasing of office and retail spaces proximate to it far more difficult. Pedestrians intentionally walked on the other sides of the streets from the park or avoided the entire area. The park’s resurgence rectified that situation. Pedestrians returned in abundance to its surrounding sidewalks. New office building and hotel projects wanted to not only be located close to it, but to claim the park’s name in their addresses. For example, the Bank of America Tower proudly proclaims its address to be One Bryant Park. However, the overall success of the commercial spaces near the park as well as the increasing strength of the Midtown CBD also had their own positive impacts on the size and composition of the park’s user pool (3).

The implications of this point can be very important for the success of small-town public spaces – redevelopment and the recruitment of residents, businesses, and nonprofits near these venues can significantly strengthen their pools of potential visitors.

Likely Pools of Potential Users in Smaller Towns.

As with Bryant Park, these pools will most likely be defined by the people who live, work, study and visit within a surrounding area, but that area will be more car trip defined than the densely urban Bryant Park’s. These pools will obviously also have far fewer potential visitors than Bryant Park’s, but then their expected user levels are also far lower.

Residents. Many smaller towns have sparse residential development in their downtown/Main Street areas, though more and more are rightly trying to correct that situation. For example, I did a deep dive into successful public spaces in three smaller communities a few years ago (see the above table). Based on my observations and discussions with local officials, I concluded that none had a significant number of downtown residents, though Somerville was developing a substantial number of new units. This means that most residents probably live beyond an easy walking distance (0.25 miles) of any downtown public space or even a doable walking distance of 0.50 miles. Another challenge is posed by the fact that most adult residents who are in the workforce will be at their employment locations during the daytimes on all five weekdays. For example, here are the percentages of working residents whose jobs are located out of town in three smaller communities:

- Valparaiso IN, population 32,000: 64.4%

- Somerville, NJ, population 12,100: 93.6%

- Greenport, NY, population 2,200: 80.3%.

Events held in a downtown public space on weekends are likely to attract the most adult residents because they are then most likely to be in-town and have free leisure time.

The types of residents who are most likely to remain in town on weekdays are retired seniors (the fastest growing age cohort in rural areas), school children, and at-home parents with pre-school children. Well designed and managed public spaces in smaller communities would do well to offer attractions that appeal to each of these demographic groups, who are likely to visit them at different times of the day.

As Andy Manshel argues so forcefully, in his upcoming book “What Works: Placemaking in Bryant Park. Revitalizing Cities, Towns and Public Spaces,( Rutgers University Press, Spring 2019),” finding successful attractions is largely a matter of trial and error, with much tweaking and recalibration, though greenery, suitable seating and easy access to food and drink are essentials. Below are some ideas about attractions that might be aimed at seniors, school-age children and parents with preschool children. They are offered as some possibilities that might be tried and tested while recognizing that there are probably many other possibilities that might be discovered by talking to members of these three potential park-user market segments:

- Seniors: exercise paths for walkers, bicyclists and bird watchers; exercise classes; chess/checkers tables; a “reading room”; a putting green. Seniors are likely to appear in the morning and midday hours.

- School-Age Children: playground equipment; bike paths; skateboard areas; soccer/football/baseball field; basketball courts; outdoor hockey rinks; summer camps; after-school supervised activity programs. School children are likely to appear after 3:00 p.m.

Childcare program in Memorial Park, Maplewood, NJ

- Parents with Preschool Children: They have a long-demonstrated the need to get out of the house and socialize with their peers. For example, in Maplewood, NJ, and Englewood, NJ, they have turned tea shops and coffee houses into places for them to congregate. In NYC, this often happens in its parks, where the parents’ young children can also be safely entertained. For example, on any nice day just take a walk around any of the playground areas in Manhattan’s Central Park (where there may be nannies instead of moms) or in Forest Park here in Queens. Appropriate seating, amply shaded, and clean accessible toilets encourage the emergence of such social clustering. These parents usually will show up from late morning to late afternoon.

Given that the numbers of potential daytime residential users are likely to be relatively moderate, a downtown public space would do well to cultivate a structured corps of potential repeat users. This can be encouraged if downtown development officials take “location enhancement” steps such as, but not limited to, these:

- Develop a community center in or adjacent to the public space that has daytime programs for seniors, kids after school and for parents with preschool children.

- Locate senior housing within a very short walk of the public space that does not entail a need to cross a street. The attractions in the public space can also serve as a development incentive for such projects.

- Invite any nonprofit that provides after-school programs for kids to use the public space.

- Invite nonprofits that have summer day camp programs to use the public space.

- If the public space has the needed playing fields, invite youth sports leagues to play on them.

- Attract a coffee shop or tea house that can attract parents with preschool children to a location adjacent to the public space.

It is also helpful to avoid a kind of downtown revitalization snobbery. Chains like McDonald’s and Starbucks are often scorned by downtown activists, but in smaller downtowns, they are regularly strong magnets that attract the available daytime residential population segments. For example:

- In Gering, NE, the downtown’s McDonald’s is its strongest customer traffic generator. It reported having consistent waves of seniors who are customers in the mid-morning and school children without adult supervision coming in after 3:00 p.m.

- In Englewood, NJ, the downtown manager reported, back in the early 2000s, that the downtown’s Starbucks attracted a consistent group of moms with pre-school children in the early afternoons.

Encouraging their opening near a smaller town downtown public space should not be dismissed out-of-hand. Of course, independents that can perform the same functions should be also courted.

The Critical Downtown Workforce. Development density in smaller community downtowns is almost always the result of the agglomeration of businesses. This means that their downtown’s critical daytime population has a lot of people who work in or near the downtown. A very interesting research project done by Ryan and Jin of communities in Wisconsin shows just how significant are the numbers of workers who are located within acceptable walking distances and easy driving times of the centers of small downtowns (4). The above table provides Ryan-Jin data on four groups of smaller towns categorized by ranges of population size: 1,000 to 2,500; 2,500 to 5,000; 5,000 to 10,000, and 10,000 to 25,000. The top four rows of data show the number of towns in each category, the number of people employed within 0.25 miles of the downtown’s center, the number of people employed within 0.25 miles, 0.50 miles and 1-mile of the downtowns’ centers.

Morristown, NJ, has more people who work there than live there. Many visit The Green at lunchtime.

In a seminal article, Larry Houstoun’s analysis of data from the first ICSC study of office workers showed that they basically averaged trips that lasted 9-minutes to and from their lunchtime destinations (5). That trip time included time spent getting out of their buildings and then the time needed to walk from their building to their destination (and vice versa). To bring the Ryan and Jin data more, if not fully, in line with Houstoun’s findings, I have translated those data into downtown employees who have an easy walk to its center, those who have a doable walk to its center, and those who are located beyond a doable walk, but still within an easy drive of the center. I have included the “easy drive” category because my projects in many suburban and rural communities – e.g., Englewood, NJ, Gering, NE, Sherwood, WI –have shown that their downtowns attract a lot of people who are within a 5-minute drive of their downtowns during weekdays.

Even the 143 towns with populations between 1,000 and 2,500 have significant daytime workforces averaging:

- 400, who are within easy walks of any public space located near the center of their downtowns.

- 354 who are within a doable 5 to 10-minute walk of such a public space

- 406 who are beyond a 10-minute walk, but within a 5-minute drive of such a space (and who probably need another four or five minutes to get to and from their cars)

Among these smallest towns, the average workforce pool of potential users totals 1,160. The larger small towns, of course, have larger workforce pools of potential users.

Even though they are likely to be very proximate to the public space, converting them into actual visitors is very challenging simply because most of the time they are in the vicinity, they are busy working. Overwhelmingly, they are most likely to visit during their lunch breaks in the 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. time period. They will need to eat their lunches on their visits – indeed, if the public space is an attractive place to eat lunch, it will attract more of their visits, so they can eat there. This means that for the small town public spaces to capture significant amounts of workforce visits, it should have:

- Quality food vendors in or adjacent to the space. They may be restaurants that do take out, fast food eateries, delis, food trucks, food carts, or kiosks. Whatever they are, they need to provide quality products at affordable prices. A public space in a good location will either have such food vendors nearby or be able to recruit them. But a public space poorly located in a fringe or low traffic area will neither have them nor be able to recruit them.

- Movable seating and tables in the space where the workers can enjoyably and comfortably eat their lunches.

The workforce users of the public space can be critical pump primers for attracting additional users. Other downtown visitors, seeing them in the public space, may also be lured into visiting it and perhaps also easting their lunches there.

Tourism. Yes, tourism can provide some small town public spaces with a significant number of visitors. For example, Greenport, NY, only has a total of 2,200 year-round residents, who have relatively modest annual incomes. and a daytime downtown workforce of 399, but its Mitchell Park attracts over 300,000 visitors annually. – day trippers from the county and beyond, second homeowners, overnight visitors at its hotels, B&Bs and marina as well as travelers passing through to use its ferries to get to Shelter Island, the Hamptons and the casinos in CT (6). Public space managers in small communities with a strong tourist flow should definitely think about ways to attract them.

That said, care should be taken to assure that the attractions the park/public space offers to attract tourists do not conflict with the attitudes and preferences of local residents. Strong, attractive parks/public spaces are usually important cornerstones of a community’s Central Social District. Nothing should be done to jeopardize that role. Indeed, strong park attractions aimed at local residents probably will also please many tourists.

Still, most smaller rural and suburban communities that I’ve visited do not have significant tourist flows, though their leaders may want to attract more out-of-towners. The focus then should be on local residents and folks who have jobs located in the community. If that is done well, then out-of-town visitors also may be attracted.

Strategically Important: Attractions That Do Not Require Much, if Any, Staff to Function

As Andrew Dane and I have written, there is a large financial toolbox available that small town leaders can use to create attractive public spaces (7). In these smaller towns, substantial financial support from the municipality definitely will be needed and essential for winning outside funding and the use of such important financial tools as tax increment financing. It probably will also be necessary to assure proper maintenance, though responsibility for programming may be given to a non-profit organization.

Recent reports suggest that parks and public spaces are now attracting increased support from philanthropic organizations and wealthy private donors (8). In Valparaiso, IN, for example, a local family recently contributed $3 million for the construction of Phase II of the downtown’s Grand Central Plaza Park.

Strategically, I would argue that the most pivotal challenge for smaller town public spaces is how to create and maintain attractions that stimulate visitors to engage in various types of activities, e.g. eating lunch or a snack, play chess or ping pong, birdwatch, ride a swing, read a magazine or book, etc. The opportunities to engage in such activities are essential if more visitors are to be attracted on non-event days.

For those concerned about how to finance the creation of these attractions and the staff then needed to operate them, there are several possible responses. First, select attractions that are relatively affordable to create and that do not require a lot of staff time, if any, to be operational. Moveable seating and tables, so visitors can eat lunches and snacks, need not be expensive to create and require no staff time to supervise. The same for climbing rocks, adult or children’s swings and chess tables. Spray pads, popular across the nation, may need a little staff time to turn them on and off. (See photos below). These examples are not exhaustive. There are other possibilities.

Some attractions that small town parks and public spaces can have that are relatively affordable to create and do not require much staff, if any, to operate: climbing racks; spray pad; adult swings and chess/checkers tables.

Other attractions may be more expensive to implement and require staff to operate, e.g., a carousel or ice rink. Their operational costs can be covered by sponsorships and user fees. It probably will take some time to attract sponsors and meaningful numbers of users.

Finally, if paying for needed staff is a problem, then perhaps volunteers can be mobilized. Of course, the reliability of volunteers can be a problem. Involving civic groups – e.g., garden clubs, chess clubs, birdwatching groups — to provide them may be one way to alleviate the situation.

ENDNOTES

1) N. David Milder. “Three Informal Entertainment Venues in Smaller Communities: Bryant Park Series, Article 4.” The Downtown Curmudgeon Blog. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/12/draft-121414-three-informal-entertainment-venues-in-smaller-communities-bryant-park-4

2) N. David Milder. “Bryant Park: The Quintessential Downtown Informal Entertainment Venue – Part 1.” Downtown Curmudgeon Blog. August 19, 2014. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/08/bryant-park-the-quintessential-downtown-informal-entertainment-venue-part-1

3) For more about Bryant Park’s location see: https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2014/08/bryant-park-the-quintessential-downtown-informal-entertainment-venue-part-1 .

4) Bill Ryan and Jangik Jin. “Employment in Wisconsin’s Downtowns.” Center for Community & Economic Development. University of Wisconsin – Extension. Staff Paper, October 20, 2011. https://cced.ces.uwex.edu/files/2014/12/Downtown_Employment_Analysis112111.pdf

5) Lawrence O. Houstoun. “NINE MINUTES TO RETAIL: The Workplace-Marketplace.” Urban Land, December 1989, pp 25-29.

6) See endnote 1.

7) N. David Milder and Andrew Dane. “Some More Thoughts on the Economic Revitalization of Small Town Downtowns: Financial Tools.” Economic Development Journal of Canada, November 2014. http://tinyurl.com/qcbnefh

8) Alyssa Ochs. “Many Things: The Surprising Appeal of Funding Community Parks.” Inside Philanthropy. May 3, 2018. https://www.insidephilanthropy.com/home/2018/5/9/many-things-the-surprising-appeal-of-funding-community-parks