By N. David Milder

INTRODUCTION

A few weeks ago, an article appeared in the Congress for the New Urbanism’s ( CNU) online journal Public Square titled “Why downtown retail is coming back ” (1). While the article had some valid and encouraging points, overall it blurred over a very complex situation in which retail in different types of downtowns have different prospects for retail rejuvenation and growth. Most importantly, there was no discussion of the enormous process of creative destruction that the retail industry is experiencing, one that promises to continue for many years to come, and that will strongly structure any rebound. Until we get a better handle on what the new retail industry will look like we cannot get a good notion about what the demand for retail locations and spaces will be. Along that line of thought, the article also ignored the facts that any comeback must be limited when the demand for retail space by national chains has had a precipitous decline and 45% of the nation’s household GAFO (general merchandise, apparel, furniture and home furnishings, other miscellaneous retail) expenditures are now being captured by online retailers.

The Public Square article makes much about increased retailer interest in “inner cities,” but this trend is anything but new. Major retailers have long been interested in and placed their stores in some types of dense urban locations. For example, by 1985, a ULI study was reporting a resurgence in downtown retailing propelled by growing CBD employment, an increasing appreciation of urban lifestyles, and a dramatic decline in the number of easy suburban retail project opportunities (2). They even have been going into highly ethnic downtowns since the late 1990s and early 2000s as evidenced by their presence in the outer borough downtowns of Jamaica Center, Fordham Road and Downtown Brooklyn in NYC. The article also failed to note that a whole lot of the major retail that is going into our inner cities is not going into their downtowns, but into large self-contained, car-oriented shopping centers that compete with the downtowns.

This raises two critical questions regarding the inner cities that are very hard to now answer:

- When the overall future demand for retail space is very likely to be far lower than in the past, will inner city locations really be getting substantially more retail stores located in them?

- How many of those new inner city retail stores will be locating in the inner city downtowns?

As for the retail chains, we know from past experience, their expressed interest in locations often is not a good indicator of where their stores will open.

The article also failed to note that most of our downtowns are in small communities that always had few if any national chains– and that is unlikely to change in the future. Nor did it discuss the prospects of the small independent retailers these small downtowns must rely on.

Yes, it can be argued that new stores are opening, and downtown retailing will not disappear. However, since it is undergoing very significant changes in magnitude and operational characteristics, it is still far too early to make any real sense of claims that it is coming back.

UNDERSTANDING THE CREATIVE DESTRUCTION OF THE RETAIL INDUSTRY UNLEASED BY THE GREAT RECESSION

What we have been witnessing in the retail industry is not the oft mentioned retail apocalypse, but a classic example, at the level of a whole industry, of what Joseph Schumpeter called the process of creative destruction — the “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” While the media, in its reporting on the retail apocalypse, has focused its attention on the destruction, far less attention has been paid to the creation of a new, vibrant and stronger retail industry, but one that may well require far fewer and smaller brick and mortar retail spaces. That would mean far fewer and smaller retail tenants for our downtowns.

The Industry’s Latent Problems. Prior to the Great Recession, the retail industry was largely ignorant of the truly bad shape it was in:

- As Elizabeth Warren’s book, The Two Income Trap, showed several years before the Great Recession, many middle income households were being financially squeezed by stagnant income growth and quickly rising costs for housing, healthcare, childcare, transportation, and education. Their retail spending was often sustained by home-based loans and/or racking up large credit card debt. The Great Recession turned these households into today’s deliberate consumers who are more cautious about their spending, much more value oriented, and demanding of bargain prices. Gone are the middle income shoppers who “traded up” prior to the Great Recession.

- In 2009, a team at McKinsey predicted that by 2011, the internet would be involved – i.e., play some role – in 45% of all retail purchases made in the USA (3). The vast majority of the retail chains seemed ignorant of that already well established trend and did not have very robust online presences, much less viable omnichannel marketing strategies. The shock and hurt the Great Recession threw at so many retail chains, the resulting consumer search for value, low prices and convenience, and the emergence of the “to the internet born” millennials, all led to a growing participation in internet shopping.

- Far too many of the retail chains were very badly managed and, of course, their leaders never owned up to that fact. Forever 21’s recent going into Chapter 11 is a classic example of this, see https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/29/business/forever-21-bankruptcy.html . Unfortunately, too many observers of the industry did not either. The problems proved to be myriad. Worst of all were ill conceived growth strategies based simply on opening more stores. Abetting that problem was a surprising ineptitude in decision-making about where to open new stores, how large they should be, and how close they should be to a chain’s other stores. Too often locational decisions were made not by rigorous analysis, but by following where other retailers were locating, especially their favored co-tenants. The old axiom that retail chains are like sheep — they like to herd — was all too true. The net result was that the chains had too many stores that were also probably too large, and too often in less than desirable locations. Many chains were also burdened by carrying too much debt, especially when they were bought out by financial firms seeking to maximize how much money that could extract from the retail operations. These new managers were not merchants, but MBAs trained in financial manipulations. The large debt burdens caused many bankruptcies. In search of profits, corporate managers cut the size and quality of their in-store sales forces, thus substantially diminishing customer service. Then, too, many chains lost contact with their customers by failing to provide the entertaining ambience, convenience, customer service, sizing and merchandise they wanted. Some chains even failed to notice that their customer base was aging out or moving on.

- Chain managers began to look more at the value of the real estate they owned or leased than increasing the profits from retail sales. Hudson Bay, for example, closed the Lord & Taylor mother store on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan not because it was losing money, but because of how much money selling it could generate. This trend continues.

- Across the nation, in the years before 2009, especially in many of our most successful downtowns, be they in big cities or affluent suburban or tourist communities, many properties with retail spaces in them were bought for very high bubble-like prices. That meant that retail rents would have to increase substantially. Moreover, the financing of these deals often meant that the retail spaces contractually had to be rented to credit worthy retail chains. When the Great Recession severely struck the retail industry, these properties and their ability to attract retail tenants were placed in a very precarious position. The purchase of the “Devil’s Building” at 666 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan was a prime example, but there were so many others.

While one can be hopeful that today’s retail chains and those of tomorrow will be far better managed than those of the past few decades, their past performance warrants some skepticism about their future behavior. Prudence also suggests that we can expect them to continue to make many serious errors, especially when subjected to the very strong pressures created in a process of creative destruction.

The Substantially Weakened Demand for Brick and Mortar Retail Locations and Spaces. The Great Recession brought these problems to a boil and resulted in many well-known retail chains going out of business, while many others are still fighting to stay open.

- Countless thousands of chain stores have closed since 2009 – for example, 7,000+ in 2017 and 7,000+ again in the first half of 2019.

- GAFO retailers were hardest hit, especially department stores and specialty apparel chains.

- The surviving chains are looking for fewer new locations, are being far more selective about locations when they do so, and their new stores are about 25% smaller than those the chains opened in the past.

- There are about 1,350 enclosed malls in the U.S., but experts believe that only 200 to 400 are needed (4). Most class “B” and “C” malls are doomed to closure and reuse.

- Also, many malls and open air shopping centers, to stay popular and solvent, are converting retail spaces to other uses such as entertainment, personal services, food and drink. Some malls are even adding housing and hotels. According to Costar, between Q1 of 2010 and Q1 of 2019, malls added about 13.9 million SF of entertainment space while open air centers added about 52.8 million SF of entertainment space (5). Most likely these additions were done by repurposing prior retail spaces.

- There is little reason to believe that similar trends are not also occurring in a large proportion of our downtowns. For example, over the past decade, I’ve seen large amounts of former retail space being leased to pamper niche – hair and nail salons, spas, gyms, martial arts studios, yoga and Pilates studios, etc. – and health care operations in downtowns across NY and NJ.

- There has also been “vacancy rate creep.” Back in the 1980s, a rate above 5% signaled cause for some concern and 10% a problem. Today, a 10% vacancy rate seems to have become accepted as the new OK normal.

- A recent 2019 report by Morgan Stanley found that while “…e-commerce penetration reached 11% of total retail sales at the end of 2018” that “e-commerce penetration in the GAFO segment” was now over 45% (6). GAFO retailers are often the ones downtown leaders most want to recruit.

- This huge capture rate achieved by online merchants plainly indicates that there will be substantially less need for GAFO brick and mortar spaces. Will rebounding downtowns, especially those in our inner cities, really be winning the lion’s share of this reduced demand?

The Small Merchant Problem. According to Statista: “There were 19,495 incorporated places registered in the United States in 2018. About 84%, 16,411 of them, had a population under 10,000.” In contrast, only 10 cities had a population of one million or more and only 310, or about 1.5%, had a population over 100,000 (7). For the vast majority of these incorporated places, small independent merchants will be their most likely retail tenants and tenant prospects. Many of these downtowns have never had a retail chain, while others were able to attract some non-GAFO chains and, more recently, dollar stores.

As can be seen in the table above, the very small merchants, those with 0 to 9 employees had the lowest decline in numbers, -7%, between 2007 and 2012, a strong indication that they were among the least hurt by the Great Recession, though there was considerable variation by state. Among them was a huge number of nonemployer firms. Many of them may have stayed open because the owner also had another job. Among the small merchants, those with 10 to 19 employees probably account for many of these small towns’ strongest retailers. They suffered a significantly higher decline, -15%, a sign they were hurt more by the Great Recession. They may have been more vulnerable because they were more likely to have had outstanding loans.

The vicissitudes these small merchants have faced were quite different than those faced by the national chains. For one thing, since most of them were not offering GAFO merchandise, they were less apt to be hurt by the growth of internet sales. In the years prior to the Great Recession, any small GAFO retailers were likely to have felt the brunt of competition from big box stores such as Walmart and Home Depot. Instead, most small town retail businesses were mainly focused on local, neighborhood type needs such as food and beverages, health and beauty products, and arts related products. However, in many smaller and less affluent downtowns, dollar stores appeared and won substantial market share – even from Walmart.

Small town primary trade areas are likely to be small geographically and sparsely populated. If they have under 15,000 people that is too small to support most independent small GAFO retailers – unless they adopt an omnichannel strategy that also produces revenue flows from online sales and offsite sales in distant market areas.

A major challenge for these very small merchants is the level of local consumer spending, since it directly impacts the cash flow they are so dependent on. Those in communities where household incomes are hardest hit will feel the pain most. Those in communities where income and population growth are stagnant will likewise probably work hard just to tread water. Retailers in small communities with strong household incomes are more likely to prosper.

Other major challenges for these small merchants are their skill sets and abilities to start and maintain a successful business. By definition, half can be expected to have below average skill sets. According to BLS data from 2016, about 56.1% of retail startups fail within their first five years. That means that the smaller downtowns towns dependent on small merchants can likely expect significant churn with the resulting need to either recruit or develop new retailers. A possible confounding problem is that nationally the number of startup firms seems to be diminishing, having fallen by 19% between 2007 and the first half of 2019 (8). How much this holds true for small retailers is not now apparent, but if the number of small retail startups has diminished, that could have important implications for many smaller downtowns.

The Green Shoots of the New Retail. On the other hand, there are many signs that brick and mortar retail will not be completely disappearing, though how many locations and how much physical space will be required are not now known. Here are some of the positive signs:

- Most Americans still prefer to shop in brick and mortar stores — 64% according to a 2016 Pew Research Center national survey; 78% also said it’s important to be able to try a product out in person (9). Several other surveys have over the years had similar findings. The problem has been that the types of stores retailers have offered shoppers have not been what many of them wanted! That is beginning to change. There has been a big increase in retail chain concerns about better instore experiences and more convenient transactions (purchasing and deliveries).

- Some chains have continued to do well through these apocalyptic times – off-pricers such as TJ Maxx; dollar stores; grocery store chains such as Wegmans, Kroger and Aldi, and beauty product stores such as Sephora and Ulta.

- Many “old” retailers seem to be learning new tricks. For example: Best Buy and Target have made notable comebacks; Walmart has created an impressive internet operation; Kohl’s is experimenting with smaller stores, bringing in Amazon returns, and putting Aldi groceries inside its stores, and Chico’s has reportedly found new online marketing legs.

- More retailers are realizing the importance of customer relationships and how convenience and instore experience can help build them.

- While chain stores have been closing, they also have been opening, if at a lower rate. Old Navy, for example, plans to double its store count and penetrate smaller communities.

- Internet birthed retailers are opening brick and mortar stores. They need them to be profitable! It remains to be seen how many stores they will open. Many of them reduce their space needs and costs by not keeping merchandise inventories onsite. Many of them like affluent downtown and neighborhood shopping district locations.

- Most importantly, retailers are now avidly adopting omnichannel marketing strategies that see both brick and mortar stores and their internet assets as related ways of connecting to their customers — and often on the same transaction. For example, it is becoming increasingly popular for shoppers to make a purchase on a retailers website and then pick it up at the retailer’s nearby physical store. Retailers are finding that physical stores can stimulate visits to their websites and conversely that websites can stimulate visits and sales in their brick and mortar stores.

- Retailers are increasingly finding that besides making sales, physical stores can play many other valuable roles related to interfacing with shoppers, e.g., being places to pick up purchases, experience/try out merchandise or receive pampering amounts of customer service. Their annual sales consequently may be a poor indication of their true value to the retail chain – or to the landlords of their leased retail spaces.

- Experimentation with smaller stores has been going on for many years now. Walmart famously tried to do so in some rural areas, and retreated. Now, a number of other chains are trying out smaller stores that allow them to enter dense urban markets where their larger formats cannot fit and/or would create traffic and/or political problems. Target has been the most visible. The argument can be made that this is an extremely important experiment for downtown retail growth. If the chains can learn how to do the smaller formats successfully more will fit not only into dense urban downtowns, but also into suburban and some rural downtowns. The key to their success may be how they use the internet and AI or AR to augment the smaller selections of merchandise they can offer in the smaller spaces.

- As I have noted in an article in the IEDC’s Economic Development Journal, there is a definite trend in some rural and suburban communities for new residents, drawn by the area’s quality of life assets, to open new retail shops (10). In several instances, these shops and eateries have become some of the best in the downtown. Quite often, those QofL retailers have been facilitated by the market shares yielded by the department stores and specialty retail chains that closed in failing nearby malls. It should be remembered however, that many of these closing retail operations had well below average market shares – that’s why they failed – and what they gave up was also prone to being captured to varying degrees by the remaining retail chains and online merchants.

LOOKING AT SOME DIFFERENT TYPES OF DOWNTOWNS

Trying to present a full typology of downtowns would require an arduous and complicated effort that would likely divert attention from the main subject of this article. Additionally, just looking at a few examples will amply serve the purpose of demonstrating different retail outcomes.

Urban Downtowns and Commercial Districts. One well-known retail expert was quoted in the Public Square article as arguing that : “Retailers have saturated the suburbs and the next underserved market is the inner cities. And they are also thinking that it will be a trend and growth market.” I found that use of the term inner city somewhat confounding since I have heard it used overwhelmingly to refer to the core poor parts of a large city that are usually heavily populated by “minority” groups, while I think the expert was really using it as a broader synonym for “dense urban areas”. Within dense urban areas several different types of retail districts can be found if categorized just by number of stores and shopper affluence – there is not just one type of inner city retail, district. Here again, to maintain some brevity, I will focus on a select few. I will look at Manhattan and other NYC retail districts simply because of the ease of finding relevant data because of my past research on them.

The Crème de la Crème. This is undeniable: in our major cities, for countless decades there have been major CBD retail corridors that have attracted hordes of trophy retailers– e.g., Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue in NYC, Newberry and Boylston Streets in Boston; North Michigan Avenue in Chicago ; Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, and Walnut Street in Philadelphia. The retail chains show how much they value such locations by not only being there, but by how much they pay to be there. For example, retail rents on the prime part of Fifth Avenue in Manhattan run about $2,871 PSF and about $960 PSF on Madison Avenue – see table above. The retailers often are there as much for the marketing opportunities provided by a “flagship store” as for the actual sales they make. That said, those sales can be huge. Back in 2009, the Apple store on Fifth Avenue reportedly had sales of $350 million, or about $35,000 PSF! Nearby Tiffany reportedly did about $18,000 PSF. (I’ve tried unsuccessfully to confirm these stats. I do not doubt that the sales PSF are very high, but they being that high, I am not sure.)

The table above is from a report by Cushman & Wakefield on 11 of Manhattan’s major retail submarkets. Unsurprisingly, Manhattan has tons of retail because it has a large, affluent population, hordes of people working there and loads of tourists, especially from abroad, who spend lots of money in retail shops. The lowest retail asking rent is in the table is $243 PSF and the average is $860. It is reasonable to assume that most of the retailers paying such rents were doing so because they expected commensurate sales revenues and profits. This shows another basic and perhaps mundane point about our retail chains – they have long entered urban commercial districts and been prepared to pay very high rents when they saw a lot of affluent people living, working, playing and spending in them. The question about retail interest in dense urban areas has really been about their willingness to enter less affluent inner city areas.

However, even these affluent submarket areas can have their problems. The Cushman & Wakefield data also show that across these 11 strong submarkets, about 21% of the commercial space is “available”, i.e. vacant or up for lease. In turn, that level of availability suggests that in these strong urban submarkets, something is not quite right. It very probably has little to do with their addressable consumer markets. Most of those consumers have benefited from income inequality, not been hurt by it. More likely are problems associated with the involved real estate properties and their tenants. Some proof of this is that when asked rents have been lowered, the availability rates also went down. There also is a real possibility that there is just too much retail space on the market, even in these posh market areas. It will be very interesting, for example, to see what happens in the 34th Street district after all the new retail space built by Related and Brookfield in and near Hudson Yards is fully activated. Also, greater retail chain entry into urban districts will depend on a lot more than just their desire to do so. It will also depend on local landlords and, as Walmart and Target have learned, the approval of city politicians. Surely, NYC is not the only big city facing such issues. Many of these major city downtowns, for example, have seen the closing or down-sizing of their department stores.

Long Successful Densely Populated Urban Districts. Here in the Borough of Queens, there are two shopping areas that demonstrate that retail chains also have long known about, located in, and succeeded in dense non CBD urban market areas with high expenditure potentials. They are also interesting because they have quite different operational characteristics and customer bases that exemplify what is happening in many of our non-crème de la crème urban commercial districts. Austin Street is a narrow two-lane street that runs parallel to the six- lane Queens Boulevard one block to its north. For about 100 years it has been the shopping area for Forest Hills Gardens and Forest Hills. Since about 1980, it has attracted upper middle income shoppers from an even wider area as such retailers as Gap, Gap for Kids, Banana Republic, Ann Taylor, Benneton, Loft, Nine West, Barnes & Noble, Victoria’s Secret, Aldo and Eddie Bauer decided to locate there– see photos above. Over the years, it has had its ups and downs usually in sync with the general economy. Recently, the B&N closed and one of Target’s “small stores” took its place, and Banana Republic and Ann Taylor have converted to “outlet/ factory” formats. In recent years, more national chains have closed than opened, with retail spaces being replaced mainly by eateries such as Shake Shack, Bare Burger, and high quality Asian restaurants, and personal services such as non-appointment doctors offices and barber shops.

There are few large commercial spaces on this traditional street, the largest being the one Target occupies that has about 25,000 SF. Attempts to redevelop this area to create much larger retail spaces would almost certainly create a political storm and likely be defeated. If retail chains are to increase their numbers on Austin Street it will likely be by those able to use value oriented formats that do not require large spaces, such as the current Ann Taylor and Banana Republic factory stores. There is no existing space for another retailer of Target’s size, or a small Whole Foods or a small Kohls.

Today, the storefronts constitute a traditional solid line of commercial activity on both sides of the street for about 0.6 miles. It has a nice scale. It is walkable, though its relatively narrow sidewalks can quickly seem crowded on weekends. It can be accessed via four subway lines, the LIRR and several bus lines, with most shoppers walking or busing there. Parking there is tight both on-street and off, and not cheap. Some of its independent retailers have been there for decades. It has some attractive eateries and bars. The whole package is very much like a successful, walkable suburban downtown and it attracts some of the borough’s more affluent shoppers who appreciate a non-mall experience. The core neighborhoods Austin Street serves – Forest Hills Gardens, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens – were early planned suburbs of Manhattan and today they maintain many suburban characteristics.

The Austin Street district’s zip code area has 68,733 residents, 61% of whom are white only. The average household income is $101,342, and the median is $76,467. About 38% of the households have annual incomes over $100,000 and they will likely account for a very disproportionate amount of local retail spending. Over 59% of its adult population have a BA degree or higher and 59% are engaged business, management, science and arts occupations. In other words, within walking distance of the retailers on Austin Street are a large bolus of creative people and lots of households with significant spending power.

Just about one mile to the west of the Austin Street district, at 63rd Drive, starts another commercial district that runs about 0.7 miles west along Queens Boulevard. See the above map. It straddles two neighborhoods, Rego Park and Elmhurst and its major retailing is a fragmented and dispersed set of shopping centers. Elmhurst is the most linguistically diverse neighborhood in the US. The character of this shopping district and its tenants are quite different from Austin street. It has the Queens Center, an enclosed mall that opened around 1980 and for several decades was one of the top grossing retail centers in the USA on a $/SF basis. It also has some power centers with tenants such as a full-size Target, Best Buy, Costco, Burlington, Marshall’s, Century 21, TJ Maxx, Aldi, and Trader Joe’s. This district is not pedestrian friendly, and its mass transit assets are a couple of second rate local subway stops. But, it’s very car oriented, abutting the very heavily trafficked Long island Expressway (LIE) and Queens Boulevard and it has loads of parking garage space. Regardless of what NYC’s planners and idealists may believe or want, most Queens residents who have cars use them frequently to go shopping at places that are beyond walking distance. This shopping district’s location allows it to tap the many shoppers with cars who live in Queens.

The Queens Center Mall offerings are those of a middle market mall. For example, it has Macy’s, JCPenny, Michael Kors, Gap, Victoria’s Secret and an Apple store. It is in a zip code that has a population of 96,353 – making it equal to a fairly large city — with median and mean household incomes of $49,098 and $65,321 respectively. About 20% of the households have annual incomes over $100,000. This shopping district is located in a solidly middle income residential area and its big box value retailers are aptly positioned both in their locations and their offerings to tap that market. However, its car orientation and location next to two highly trafficked roadways means it also can draw many shoppers from well beyond its zip code.

This district does not operate in any way that resembles what a well-designed and well run downtown should be. If this is the model for today’s retail chains to penetrate our urban areas, then there may well be strong reasons to question the value of their entry. Over the past decade, for example, some big box operations have entered Jamaica Center – Marshalls and Home Depot – but observers report that their shoppers, who mostly arrive by auto, do not spend much time walking around and shopping in other downtown stores. it is hard to see how the insertion of power centers or even a mall as magnetic as the inward-looking Queens Center, would do much to help other nearby downtown retailers or make the district to appear more vibrant. For example, part of the reason The Gallery in Center City Philadelphia failed is that it was not very permeable to pedestrians on Market Street. Fashion District Philadelphia, the heavily renovated mall that replaced it, reportedly is far more permeable for pedestrians.

Underserved Inner City Districts. Now let’s look at the inner city downtown and neighborhood districts where large numbers of lower income, non-white populations shop. Over the years, I have done a lot of work in places such as Jamaica Center in Queens; Fordham Road, Norwood and Hunts Point in The Bronx; Downtown Brooklyn; and West New York and Elizabeth in NJ. Since the early 1980s, I’ve heard about these districts being underserved by retailers and on many occasions I, too, made that argument. There is absolutely nothing new in that argument. What I usually found was that:

- Local leaders, landlords and a tranche of middle income trade area residents were dissatisfied with the retail offerings as well as the district’s appearance and fear of crime.

- Yet, there were numerous shops, fairly normal vacancy rates, and the sidewalks filled with pedestrians during the daytime . After visiting a few of them, one former president of Bloomingdale’s called them “beehives of activity.”

- Over time, the dissatisfaction increased as the retail shops stopped serving middle income shoppers and focused more on lower income, “ethnic,” and teenage shoppers.

- In seeming validation of Michael E. Porter’s famous argument in “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City,” that dense low income populations in aggregate offered strong market potentials, the inner city retailers who focused on lower income shoppers very often reported strong sales PSF that rivaled those reported for some of Manhattan’s posh shopping corridors (11). Indeed, some were doing so well that they created their own chains that opened stores in inner city downtowns and large commercial centers across the NY-NJ-CT metropolitan region and even in PA.

- Trade area analyses of these downtown and large neighborhood shopping districts consistently showed that the number of solidly middle income households were either sizeable or even in the majority, and certainly accounted for most of the retail spending power. For example, the 1987 report I co-authored with Bill Shore on Jamaica Center found that the households in its trade area had a 10% higher average income than those in NYC as a whole (12). In 2002, DANTH looked at the trade area of the Jerome Avenue BID in The Bronx and found the median household income in 2019 dollars was about $76,234 and 22.8% of the households had incomes in 2019 dollars above $109,889. What Porter appears to have missed is the fact that while many and probably most of our inner city commercial districts may be drawing from areas that are indeed heavily “ethnic,” with many lower income people, they also can have large numbers of solidly middle income and even upper middle income households that have most of the spending power.

- Nonetheless, the retailers in these inner city districts were targeting the trade areas’ lower income residents and less affluent district visitors. In many instances, the low income segment was targeted by the retailers because they lived in or near the downtown and were its most frequent users. The market research of too many of these retailers was limited to observing the types of people they saw walking by their shop or possible location. More importantly, the retailers very often were making very sizeable profits – Porter did see this possibility –and saw no reason to take the risk of trying to attract their market area’s more affluent shoppers.

Jamaica Center. NYC has several outer borough downtowns. Jamaica Center is one of the three in Queens. It is old, dating back to the colonial days. In 1947, when Macy’s opened its second branch store in NYC, it was in Jamaica Center. It was long a true, multifunctional downtown. However, by the late 1960s, it faced a steep decline with white residential and retail flight. In the late 1990s, and especially after Porter’s article received wide national attention, some of the more sought after national chains started to look more closely at dense inner city downtowns, and Jamaica Center was one of them. By 2002, for example, One Jamaica Center, a 450,000SF a mixed-use complex was opened with tenants such as Old Navy, Gap, Bally Total Fitness, Walgreens, Subway, Dunkin’ Donuts, a 15-screen multiplex theater. Marshalls, Home Depot,, Footlocker, Petland also have located there. Just opened are H&M and Burlington Coat Factory. Among those that have come and gone are Payless, Toys R Us, Kids R Us, The Athlete’s Store – retailers troubled at the corporate level. Gap is now in another location and using a factory store format. Jamaica also still has lots of the chains that have long felt comfortable being in inner city commercials districts such as Fabco, CH Martin, Conway, Danice, Rainbow, Shoppers World, Young World, GNC, Game Stop, Jimmy Jazz, Dr Jay’s, and Vim. Target is reportedly may locate in a new mixed use project and it will be very interesting to see if it is a small store or one of its larger formats. The smaller Target stores I’ve seen in urban locations are not in inner city ethnic districts — my experience may be limited – but in very solid upper-middle-income, non-CBD commercial areas such as Austin Street or on East Illinois near the lake in Chicago.

The emergence in Jamaica Center of a cluster of well-known national retailers who appeal to middle income shoppers looking for value in their purchases is a process that started many years ago and continues on today. There has not been any sudden huge gush of retail interest, but a long-term series of stops and starts that is building a herd of retail sheep that hopefully will reach the critical size needed to attract more retail sheep. Notably, this meeting of middle income retail demand is being done by retailers with value formats – even the specialty apparel retailer, Gap, is using one. There was normal churn, but no new large influx of retailers targeting poorer shoppers – those retailers were long there.

Jamaica Center had several existing large commercial spaces that could be converted for use by these big box value operations. Among them were old department stores, an old newspaper building and large former furniture stores. When will the supply of those large spaces run out? What, if anything, will be done then to create new ones?

Very importantly, for the first time since the early 1960s, a very substantial number of new housing units are appearing in Jamaica Center. One might suspect they will intensify retail chain interest. If so, that points to the strong possibility that if other inner city downtowns are now enjoying first time or greatly increased retail chain interest, it may be because they have improved in important ways that made them more attractive to retailers — and less because the retailers have suddenly seen the light and are newly interested in inner cities. Greater interest in downtown Detroit, for example, by retail chains that are now doing well, would not be surprising given the significant revitalization that has occurred there in the recent past.

Lessons to learn From the Retail Growth in The Bronx. There are perhaps no better examples of poor ethnic inner city neighborhoods than those found in The Bronx, NY. It has 1.5 million residents, a population density of 32,903/SqMile, the lowest per capita income among NY’s 62 counties, and only about 10% of its population is white only. For decades, the fact that the entire borough was badly understored was widely acknowledged, and largely ignored by retailers and developers. However, in a slow, start and stop manner, retail has been growing in the borough since the opening of the powerful Bay Plaza Shopping Center in the mid 1987, with another burst in the early 2000s and considerable growth since the Great Recession. The table below lists the major shopping centers in the borough and provides some demographic information about them. Since around 2000, well over 3 million SF of new retail space has opened in The Bronx, with over 2 million SF since 2009.

Fordham Road and The Hub are the two shopping districts with the physical characteristics most like those of a downtown. They are also in the zip codes with the greatest population densities and the lowest and third lowest household incomes. Both have strong subway assets and Fordham Road has an increasingly used Metro North station next to a large bus transfer point. Both have comparatively little off street parking and are not that close to a major highway. However, these two downtown-like districts have attracted a relatively small portion of the new retail. The Hub has seen little to no real growth. The 300+ store Fordham Road district has done better. It remains a beehive of activity well after two major department stores closed: Alexander’s and Sears. It has attracted a significant number of national chains: American Eagle Outlet, Best Buy, Claire’s, Footlocker, GameStop, Gap Outlet, Macy’s Backstage, Marshall’s, Nine West Outlet, Payless, Rainbow, Sleepy’s, Staples, Starbucks, The Children’s Place, TJ Maxx, Walgreens and Zale’s. Many of the larger chain tenants – Marshalls, TJ Maxx, Best Buy, and Macy’s Backstage have gone into the buildings vacated by the department stores. Here, as in Jamaica Center, large value and outlet retailers are important. There are few if any large retail prone spaces of say 25,000+ SF available and that is probably constraining the district’s ability to attract more major retailers.

Most of the new comparison retail in the borough has gone into the other shopping centers listed in the table. The characteristic they all share is that they are car oriented: they sit next to major highways and have lots of off-street parking. They plainly are targeting shoppers who are located well beyond the neighborhoods they are located in. For example, Target is an anchor tenant in three of them and claims addressable trade area populations of 400,000+. The retailers entering into this paradigmatic inner city county are showing by their stores how much they nevertheless still favor self-contained car-oriented shopping centers over downtown-like locations. To some degree, this may be because of the lack of appropriate spaces in The Hub and along Fordham Road.

The Bronx Terminal Market (BTM) is a 913,000 SF retail complex that opened in 2009, despite the Great Recession, is perhaps the strongest example of the retailers continued preference for strong highway access locations. It is owned and operated by the Related Companies, one of the largest real estate developers/owners in the USA. Its presence in the Bronx more than 10 years ago certainly demonstrates that the interest of important retail developers and retail chains in The Bronx is not new. The new Yankee Stadium also opened in 2009. With the new stadium, political leaders and the Yankee organization wanted the surrounding area improved. Metro-North put in a new station, existing subway stations were improved and the BTM was built. Its tenant list included: Babies R Us, Bed, Bath & Beyond, Best Buy, BJ’s, Burlington, GameStop, Home Depot, Marshalls, Michael’s, Raymour & Flannigan, and Target. That’s one powerful retail line up! Those retailers need to draw from a very wide and densely populated trade area, one that probably goes well beyond the South Bronx. The BTM’s location right next to I-87 allows such market penetration. Aside from that asset, the BTM’s location is not a particularly desirable one for retailers. It is located in a relatively low-income zip code that has a population density that is far from the highest. Its strong car orientation indicates that while it certainly might draw some close by lower income shoppers, its primary customer base will be middle income shoppers located along the I-87 driveshed.

The Kingsbridge Broadway Corridor in Zip Code 10463 has attracted three shopping centers that together total 530,000 SF. The first opened in 20004 and the other two in 2014 and 2015. They too sit very near an I-87 exit. Their zip code’s residents are solidly middle oncome and 24% of the households have annual incomes of $100,000. This corridor is very interesting because retailers there can tap the close-in Kingsbridge, Riverdale and Inwood neighborhoods. The three shopping centers have definitely increased the retail choices of local residents. The distances between these three shopping centers are certainly walkable, but the way they are built and the setting along Broadway are not conducive to making such walks. They are not downtown-like and have done little to stimulate the creation of a walkable shopping district along this section of Broadway.

The 300,000 SF Throggs Neck Shopping Center that opened in 2014 is in a similar type of location. It is next to an exit on I-95 and the residents on its zip code are solidly middle income, with about 23% of the households having annual incomes of $100,000. The Targets in this and the River Plaza shopping center both have their main sales areas underground, as does the Costco in Rego Park. This was done to bypass the zoning aimed by city fathers at deterring the opening of large big box stores.

The New Horizons Shopping Center is a supermarket anchored center in a low-income neighborhood. It was created through the hard work of a terrific neighborhood organization, the Mid-Bronx Desperados (MBD), that worked with LISC. Today, it has a Stop & Shop, Auto Zone, TJ Maxx, Footlocker, Petland, Game Stop, Subway, IHOP and Taco Bell. This is a traditional suburban type, car oriented shopping center, with shops located in a sea of parking spaces. It is also very close to the Cross Bronx Expressway. It is not an urban shopping project with a solid wall of shops on the ground floors of buildings that abut and open to sidewalks. On the once infamous Charlotte Street, MBD had previously built ranch style single family residential units. Their occupants have well-tended backyards, some boats sitting in driveways and some above-ground swimming pools. Given their MBD origins, both the housing and the shopping center certainly reflected local aspirations and needs. Residents in many other dense, low-income, ethnic urban areas may also aspire to more suburban type retail projects. Because people are less affluent does not necessarily mean they like downtown or other urban retail environments. That may prove to be another challenge to inner city downtown retail growth.

The Bay Plaza Shopping Center and Mall is an example of a large and growing suburban mall, but one located in the middle one of the most densely populated, highly “minority” and poor counties in the nation. It is isolated in the geographic arm fold of two major highways, I-95 and the Hutchinson River Parkway, and only accessible by car or, with some difficulty, bus. It plainly is targeting middle income shoppers not only in The Bronx, but also in lower Westchester County. Opened in 1987, it has grown to over 2 million SF, adding 780,000 SF in 2014. Its tenants range from traditional department stores (e.g., Macy’s) and specialty retail chains (e.g., Victoria’s Secret) to the value pricing department stores (Marshall’s and Saks Off 5th) and retail chains (DSW). Also included are several regional chains such as Easy Pickins and Jimmy Jazz. Importantly, they have also attracted retailers who are big hits with teens and young adults, such as H&M, Forever 21, and Hot Topic. The array of national retailers in this mall far outshines what The Bronx’s closest approximation to a downtown, Fordham Road, has to offer.

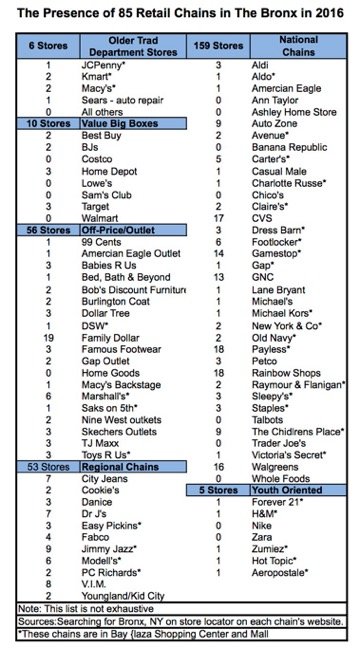

Back in 2016, I compiled a list of 85 national chains and researched how many had locations in The Bronx (13). See the table above. While the list certainly was not exhaustive, the results are hopefully still informative. I found 75 of the identified chains had Bronx locations and together they had a total of 290 stores.

As might be expected, The Bronx still has not attracted. the likes of Gucci, Prada, Valentino, Tiffany, Duxiana, Ralph Lauren, etc. They are far, far too ritzy and more appropriate for Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Midtown Manhattan or the Americana Shopping Center in Manhasset, NY. Nor is The Bronx attracting, perhaps thankfully, those like Talbots, Chico’s, Ann Taylor or Banana Republic – many of these apparel chains still are fighting for survival. Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods still have stayed away. So have Walmart and its sibling Sam’s Club – due more to strong political opposition in NYC to Walmart than the chain’s lack of interest in NYC locations.

The retail chains that now seem to like the inner city Bronx’s markets the most are those:

- Aiming at the lower income and ethic shoppers: e.g., Family Dollar, Dollar Tree, Dr Jays, Jimmy Jazz, Rainbow Shops, Vim and City Jeans. Many of them have been around for decades.

- With a neighborhood level store location strategy: e.g., GNC, Walgreens, Payless, GameStop, AutoZone and CVS. These types of retailers have been locating in ethnic inner city districts since the mid 1980s.

- Targeting middle-income shoppers in either big box, off-price, or factory outlet formats. Includes Home Depot, BJs, Best Buy, Target, Burlington Coat, Marshall’s, TJ Maxx, DSW, Gap Outlet, American Eagle Outlet, Macy’s Backstage, Nine West Outlet, Aldi, Saks Off 5th. These are more likely to have arrived after 2002, but some go back to 1987.

The retailers honed in on the middle class now operate in ways that recognize its huge number of deliberate consumers who are:

- Much more value conscious.

- Cautious spenders.

- Expect big price discounts from retailers.

SOME TAKE AWAYS

1. What national retail chains may do is largely irrelevant for a very large number of our downtowns that are small. They either never had any chains or only had a few non-GAFO chains. Their trade areas often are far too sparsely populated – e.g., probably under 15,000 people –to support small GAFO retailers. In these small downtowns, the abilities of local merchants will be a more critical factor than the behaviors of national retail chains.

2. Most needed in these small towns are better merchants, through either recruitment or re-training.

3. That our inner cities are underserved by retailers has been recognized at least since the early 1980s. This is not a new situation, nor is the awareness of it.

4. National retail chains, probably since their inception, have been interested in prime urban locations where lots of wealthy people lived and played, and they have been prepared to pay a lot for them. Their locating today near to large new market rate housing projects, especially if they are expensive, or in a walkable or TOD neighborhood, absolutely comes as no surprise. What would be a surprise, is if they behaved otherwise.

5. For over 20 years, national retailers have been locating in highly ethnic inner city districts and downtowns, but the levels of their interest have been uneven over time and across places. The questions sparked by the Public Square article are: a) will retailers now locate in our inner cities at a higher rate than before, even though their demand for new retail space has significantly decreased, and b) will those stores be located in our inner city downtowns?

6. The retail demand of low income shoppers in these inner city districts were long met by local retailers, who often had lucrative businesses and created chains targeted to low-income shoppers in similar districts.

7. Middle income shoppers were the most underserved and complaining inner city market segment. They were often surprisingly numerous and accounted for a large proportion of an inner city area’s residential retail expenditure potentials.

8. National chains that usually targeted middle income shoppers have over the past 20 years increasingly entered inner city districts, targeting, as might be expected, local middle income shoppers. It is their presence and not the density of the low-income shoppers that attracts these retailers.

9. The retailers best positioned to capture middle income shoppers these days are those that feature strong value pricing in either big box, off-price or factory outlet formats. These are precisely the types of retailers that are entering densely populated inner city areas.

10. Many of them require relatively large spaces and are accustomed to being in very car oriented retail centers. They often are hard to fit into a downtown, especially if it lacks large retail prone spaces and parking capacity. Consequently, these retailers may prefer to locate in non-downtown inner city locations, and downtowns might not benefit so much from any increased retail chain interest in inner city locations.

11. The use of smaller formats theoretically could enable more of these chains to locate in downtowns, but their viability is still being tested and their placement in ethnic inner city districts now is still uncertain.

12. Most importantly, the retail industry remains in the midst of a process of creative destruction that does not promise to end any time soon. As a result, how much retail space will be needed in the future remains unknown, though it now looks like it will be considerably less than it was even a few years ago. Also, still to be clarified, are the uses the retail spaces will be put to, and how that will impact the amount of space needed, their best locations and costs. These factors all have strong possible implications for any downtown retail rebound.

13. Many other factors, besides the interest of the retail chains will determine how a downtown’s retail will rebound. Among them are: the abilities and behaviors of retail chains’ managers and local landlords; political, urban design and environmental issues, the availability of appropriate retail-prone spaces and ample parking, and, most importantly, where and how local consumers like to shop.

14. There are some other interesting types of downtowns that appear to have their own retail development scenarios these days: downtown creative districts; the lifestyle mall suburban downtown; the urbanized suburban downtown; the rural regional commercial center downtowns, and the small rural downtown gems. Unfortunately, I cannot cover them in this already long article, but I want to acknowledge their existence.

ENDNOTES

1. Robert Steuteville SEP. 10, 2019, “Why downtown retail is coming back”. PSQ (/publicsquare). https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2019/09/10/new-day-downtown-retail

2. Urban Land Institute, Downtown Retail Development, Washington, DC:1985, pp 90, p.5

3. “The promise of multichannel retailing”, McKinsey Quarterly, October 2009,pp2-4,p2.

5.Data from Costar, cited in: ICSC, “Expanding Entertainment Tenants Add Experiences to Shopping Centers (Part I)” August 19, 2019. https://www.icsc.com/uploads/t07-subpage/Entertainment_Part_I_Industry_Sector_Series.pdf

6. see: https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/us-consumer-retail-trends-2019

7. See: https://www.statista.com/statistics/241695/number-of-us-cities-towns-villages-by-population-size/

9. Aaron Smith and Monica Anderson, “Online Shopping and E-Commerce,” Pew Research Center, December 19, 2016. https://www.pewinternet.org/2016/12/19/online-shopping-and-e-commerce/

10. N. David Milder. “quality-of-life based RETAIL RECRUITMENT.” Economic Development Journal 16.3 (2017): 38-45.

11. Michael E. Porter, “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City.” Harvard Business Review

May–June 1995.

12. Milder, N. David and William B. Shore. Jamaica Center 1987: An Office Enterprise Zone. Regional Plan Association, New York:1987, pp. 53, p5.

13. N. David Milder with Dart Westphal. “The Bronx, NY: Low-Income, High Immigrant, Minority-Majority Urban Areas May Fare Relatively Well Under Retail’s New Normal” Downtown Curmudgeon Blog. December 2016. https://www.ndavidmilder.com/2016/12/the-bronx-ny-low-income-high-immigrant-minority-majority-urban-areas-may-fare-relatively-well-under-retails-new-normal?(opens in a new tab)