By N. David Milder

Who Are They?

Many downtown retail growth strategies are doomed because they try to avoid some key facts. One is that, except in the very rarest of rare situations, downtown retailers, be they new or old, large or small, must compete for and win sufficient market share to prosper. Another, and closely related fact, is that beneath the venerated “leaked” sales to merchants located beyond the downtown’s trade area, and the 45% of GAFO sales now being e-leaked to online merchants, is a group of shoppers who are either weakly bonded or completely unbonded to merchants in either the downtown or its larger trade area. They are “up for grabs shoppers” who are very likely to buy fewer things, or to be won over by strongly magnetic brick and mortar merchants located beyond the trade area, or by online merchants, or—and this is very important – by new retailers opening in the downtown or elsewhere in the trade area.

Some Implications

The existence of such shoppers has important implications:

- The up for grabs shoppers are always there, though their numbers may vary across retail sectors and over time.

- For new and expanding downtown retailers, it means that there very often will be between 15% to 60% of the shoppers in their retail sector who are up for grabs and likely to give them a look. That indicates the local competition is weak. If the new/expanding retailers are capable, they will have a very good chance of winning the dollars and loyalties of these shoppers.

- For many existing retailers, the up for grabs shoppers can indicate – if they learn about them — that a good percentage of their customer base may be prone to desertion and signal a need for the merchants to improve their operations.

- For downtown economic strategists and leaders, it means that any successful new retailer brought into town is likely to win customers away from merchants located beyond the trade area, or from online merchants, and/or from brick and mortar merchants currently located in the downtown or elsewhere in the trade area. The existence of substantial numbers of up for grabs shoppers also is a sign that downtown EDOs need to create effective programs to help existing merchants improve, or to be prepared to recruit more capable merchants who can better satisfy consumer needs and wants.

- Just looking at the shoppers leaking their retail expenditures to beyond the trade area merchants is rather myopic – and a denial of reality. This myopia is understandable given that it seems to allow for the ill-conceived assumption of immaculate retailing that any new or expanding downtown retailer competing for the leaked dollars will not take any sales away from other downtown merchants. The existence of any sizeable number of up-for-grabs shoppers in the relevant retail sector means that is a highly unlikely prospect.

Some Examples

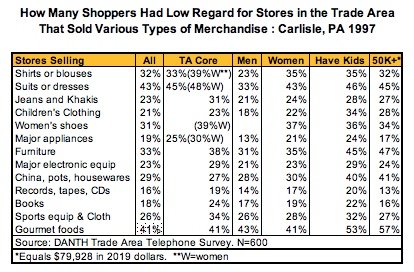

DANTH, Inc. first addressed up-for-grabs shoppers in a number of telephone

surveys we did back in the 1990s when we asked respondents whether various types of retail stores they

could visit within a 20-minute drive

from their homes, were excellent, good, fair, or bad. Responses of fair and bad

were treated as indicators of weak bonding with the relevant retailers. Their

retail expenditures consequently may be considered as up-for- grabs and more

prone to being captured by new or expanding retailers, be they brick and mortar

or online. Above are two tables showing

the responses to surveys done of the shopperss in the trade areas of Rutland,

VT, and Carlisle, PA. For example, about

44% of the expenditures for suits or dresses by shoppers in Rutland’s trade

area were up-for-grabs, as were about 43% of those expenditures by shoppers in

Carlisle’s trade area.

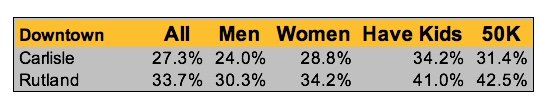

For all the retail store types, the average number of loosely bonded shoppers in Carlisle’s trade area, 27.3%, was somewhat lower than that in Rutland’s trade area, 33.7% — see the table above. This may be because Carlisle is in a denser region, with higher household incomes, and with many more retail choices. Downtown Rutland is located in the Rutland Micropolitan Statistical Area that is composed of Rutland County. The median household income in 2017 in the county was about $52,000, and about 19% of the households had an annual income of $100,000+. The county has a population of about 61,000, and Rutland City is by far its largest retail center. In contrast, Downtown Carlisle is on the western edge of the Harrisburg–Carlisle MSA that had a population of about 560,000. Carlisle is located in Cumberland County where the median household income in 2017 was over $82,000, and about 27% of the households had an annual income of $100,000+. Moreover, back in 1997, in the downtown Carlisle trade area there were 12 major malls occupying a total GLA of about 3.5 million SF.

It is also interesting to note that, even with all that retail within an easy drive, on average, 27.3% of the shoppers in Carlisle’s trade area were up-for-grabs. Moreover, that number was even higher for some important markets segments: shoppers with children and those with annual household incomes over $50,000 (about $80,000 in 2019 dollars). The same pattern among market segments was even stronger among Rutland’s shoppers.

Some Types of Up-for-Grabs Shoppers

Up for grab shoppers can be present in many market segments and to varying degrees. For example, the numbers/percentages of loosely bonded shoppers in the upper income 4th and 5th quintiles are of particular interest because they account for a very disproportionate amount of consumer expenditures across all sectors, especially retail. As can be seen in the above table, nationally, shoppers in the highest income quintile (the 5th 20% group) accounted for about 38.9% of all consumer expenditures in 2017, about equal to the combined total of the 3rd and 4th quintiles. The 5th quintiles shares of all expenditures on food away from home, home furnishings, and apparel were at about that level. However, they also accounted for 52% of all entertainment fees and admissions, making them an absolutely critical market segment for most downtown entertainment niches.

In rural towns and cities, such as Rutland, VT, Scotts Bluff, NE and Laramie, WY, where trade area populations are not large and household incomes are relatively modest, one might expect the more affluent shoppers will be among those most detached from local merchants. These downtowns usually do not have a strongly varied retail environment and local merchants are prone to catering to the more numerous middle income shoppers. Underserved, and possibly ignored, these more affluent consumers tend to shop in distant towns and cities having more robust retail assets, and they are increasingly buying from online retailers.

Very often, a large proportion of leaked retail expenditures come from the 20% to 30% of the households with the highest incomes in the trade area. Unless a sufficient bolus of the types of retail they prefer open in the downtown or trade area, it will be very difficult to recapture those leaked dollars. Traditional leakage analyses, by themselves, cannot identify such situations. However, an analysis of the up for grabs shoppers can help answer the critical question that leakage analyses raise, but cannot answer: how many of the leaked dollars can be captured by new or improved local merchants?

Lower income shoppers also can be up for grabs. The local retail structure also may not have the stores with the price points and/or merchandise they need. Evidence of this comes from the enormous growth in recent years of dollar store chains and their ability to take significant numbers of low-income shoppers away from huge, well-established retailers such as Walmart, as well as from local small merchants.

It should be noted that an important element in the discussions of upper and lower income shoppers presented above is the existence of what might be termed a gap between the types of stores these shoppers need and/or want and those that exist in the downtown or trade area. A useful estimate of the monetary values of such gaps can be made by multiplying the number of dissatisfied shoppers by sector in the relevant income groups with estimates of the retail expenditures by sector of households in those income groups. However, such estimates do not carry along with them the assumption that all of the potential gap expenditures are being leaked to beyond the trade area merchants. Shoppers might also spend online, or simply reduce their spending levels.

The discussions of these two income groups also helps spotlight a frequent deficiency in downtown market analyses: the primary focus on statistical means and medians.

Millennials, now our largest generation, seems very prone to being weakly bonded to product brands. One might reasonably hypothesize that also will probably be the case for retailer brands. For example, in 2017, a study found that “67 % of millennials changed brands in the last year” and called this “a clear lack of brand loyalty among 18-34 year olds.” The two major factors driving disloyalty were product quality (49%) and product availability (44%). These findings suggest that the number of up for grabs shoppers is likely to grow in importance in coming years as the economic importance of the millennials grows. See: “Millennial Research: Factors Driving US Millennials Brand Disloyalty”, Posted on January 20, 2017 by B. Smith to https://www.customerinsightgroup.com/loyaltyblog/brand-loyalty/millennial-research-factors-us-millennials-brand-disloyalty

Here’s the Rub

In my experience, telephone surveys with about 500 to 600 respondents were the best way to obtain useful and reliable data about the up for grabs shoppers in a downtown’s trade area. However, over the past two decades, it has become harder and harder to conduct such surveys. Response rates have dropped significantly as the public became more resistant to answering surveys and responding to telemarketing efforts. Online surveys are not a substitute, since their use really requires a panel of respondents from which a valid sample of trade area respondents can be drawn. Few, if any, trade areas have such panels.

As a result, for many years we stopped doing trade area telephone surveys, yet the need for the types of data they could provide seemed to grow with the upheavals in the retail industry and the need to get a good grip on how many sales were going to online retailers. Today, in the face of that growing need, the best available solution path appears to be one framed by an analytical modesty that recognizes we will have to deal with survey data that is far less accurate than we might like. For example, it may be necessary to accept a 5% or 10% estimate error at the 85% or 90% confidence level. These can be maximized when the population being surveyed can be treated as finite. Furthermore, the solution path might utilize several of these research tools:

- Shopper Intercept Survey. The value of these surveys depends a lot on where and when the interceptions are made and the number of interviews that are completed. The more completions the better. That number will be determined by where the interceptions are made, the length of the questionnaire, the ease of answering the questions, and the respondents interest in revitalizing/improving the downtown. Given the need for brevity –- say 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire – it will be essential to carefully select the most important questions. In the past, we limited our use of shopper intercept surveys because they seemed limited in their ability to gather all the information that a telephone survey could. Furthermore, they could not reach the trade area shoppers who did not shop downtown and obtain information from them that might help explain why. That said, the need to get some useful data about these up for grabs shoppers has grown to the point that we are faced with the choice of either rejecting the use of any survey data or using surveys that may not have the error and confidence levels held as the acceptable standards in the past. One can argue, that if the conclusions drawn from a survey with a 7% or 10% error factor at an 80% or 90% confidence level are carefully structured, they still can be very useful analytically. The analyst is certainly in a better situation having access to such information than not having it.

- Online Surveys. In a number of instances, some market segments may be known to be more important than others and merit special attention. The size of such a market segment and viable ways of contacting its members also may be known. That means that huge proportions of the relevant population, possibly even every member, can be invited to participate in an online survey. In these situations sampling is either not an issue or not a significant one. This is often very true of important segments in a downtown’s daytime population: people employed in the downtown, seniors in downtown housing and senior centers, high school students, patrons of downtown cultural venues, users of downtown transportation centers, downtown residents, etc.

- Nominal Group Process (NGP). We like this small group process because its structure prevents the discussion being dominated by a few participants and assures a useful information product will be produced at the end of the session. The NGP is able to handle 100 to 150 participants grouped in 10 to 12 tables and then the results often can be stated in quantitative terms. However, the qualitative inputs generated by participants are usually the primary useful products.

- Focus Groups. These small groups can be useful, but too often are not. They best provide qualitative information, Using them to predict market segment behaviors is ill founded, since the number of participants is usually too small to constitute a useful sample and their characteristics and recruitment are unlikely to be representative of the relevant population. If not well-led and/or are too large , focus groups can be dominated by a few individuals. However, the qualitative information they often can produce can give the analyst an understanding that simply cannot be provided by just the numerical data. They can be invaluable for generating viable explanatory hypotheses.