By N. David Milder

With Dart Westphal

Introduction.

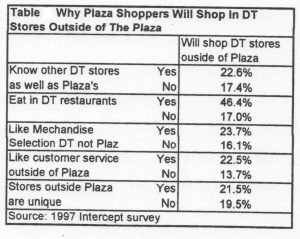

Why the Emphasis on Retail Chains. In previous articles in this series, I have demonstrated how small independent merchants are essential to the success of many small and medium-sized downtowns. They are even the retailers that have meaningful growth opportunities in these communities. However, in my assignments in urban lower-income, ethnic commercial districts, local stakeholders and trade area residents equated retail revitalization with the attraction of stronger, higher quality retail chains. The existing independent merchants and small chains were viewed as mostly not adequately serving their local communities. The small merchants were seen as unable to offer the merchandise selection and price/value benefits shoppers wanted. Consequently, in this article, my focus is on retail chains. In a later article, I will take a deep dive into why it has become so much more difficult for small merchants to succeed in our larger cities.

Why The Bronx? This county, that is also a borough of New York City, has certainly received a lot of notoriety since Howard Cosell, several decades ago, harmfully declared on national TV that it was burning. It still is poor, ranking 62nd of NYS’s 62 counties on per capita income and median household income. It has a minority population majority: most of its residents are Blacks, Hispanics and Asians. It also has a strong immigrant population. Thankfully, today, it is no longer the borough of Cosell’s rant. Though major problems and challenges remain, there have been notable improvements.

One that caught my attention is in retail. Since the early 1980s, I have been researching retail districts all over the Bronx, e.g., the Hub, Fordham Road, Hunt’s Point, Jerome Avenue/Gun Hill Road, Belmont and Baychester. In my opinion, today’s Bronx residents have a greatly improved array of national and local chains to chose from. Perhaps even more importantly, the borough is attracting, in strength, the types of retailers that are flourishing today under retail’s new normal and who promise to continue to thrive well into the future. Moreover, because the borough long has been so badly understored, some types of retailing that are struggling in other geographic areas are finding surprising traction in The Bronx.

While this article is part of a series looking at how retail’s new normal is playing out in various types of downtowns, I decided not to just focus on the Fordham Road corridor — which is the closest The Bronx comes to having a genuine downtown – because that would avoid putting the spotlight on some really significant things happening in the borough that are relevant to understanding where retailing can go in other large urban areas.

Density Is Important, But Other Factors Need to Be Looked Into, Too. For example, the pattern of recent retail development in The Bronx suggests that the competitive advantage high population density can give inner cities may also play out in ways other than simply the aggregation of a large number of low income households, as Michael Porter famously proposed:

“The first notable quality of the inner city market is its size. Even though average inner city incomes are relatively low, high population density translates into an immense market with substantial purchasing power.” (Michael E. Porter, “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City,” Harvard Business Review, May–June 1995, https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city)

Instead, many of the borough’s recent major retail projects are aimed at attracting The Bronx’s badly underserved middle income households and those shoppers, with cars, who live outside of The Bronx. Density also means The Bronx has a significant number of middle income households.

A report done in 1990 for Regional Plan Association’s New Directions for The Bronx project noted that retail growth was severely impaired by the lack of available appropriate land needed for such projects. Retail development in The Bronx over the past 15 years, however, suggests that developers have been able to find, often quite cleverly, the needed parcels. It also suggests that access to major highways, the presence of adequate parking and having the appropriately sized retail spaces also are very important locational factors — even in very dense urban areas. This importance of auto travel was not surprising to me. As a resident of one of NYC’s “outer boroughs,” I know that while I and my fellow citizens will take mass transit to get to and from Manhattan, we vastly prefer using our cars when shopping for department-store like merchandise outside of Manhattan. In fact, many of our retail shopping destinations have been designed to be reached primarily by car. When outer borough shoppers do not own a car, they often will use instead a livery service vehicle.

Political and social factors have also played important roles in determining the locations and characteristics of some new retail projects in The Bronx. Politics and development/redevelopment are never far from each other.

Of course, not all retail projects in the Bronx have succeeded. Concourse Plaza is a disappointing failure close to both Borough Hall and Yankee Stadium. It also took a lot of trial and effort to get something successful going on the Bronx Terminal Market site.

A Data Snapshot of Today’s Bronx Residents.

The Bronx’s total population is large, just under 1.5 million, making it equal to the sixth or seventh largest city in the USA. If population density is a competitive advantage, then The Bronx has it in spades, with a density of 32,903 residents per square mile. It ranks third in population density among all of the nation’s counties, right behind Manhattan and Brooklyn. In comparison, the whole city of Laramie, WY has a population of about 32,158 living in a 17.7 square mile area.

So-called minorities dominate The Bronx’s population. While about 62% of the U.S. population are Non-Hispanic whites, they only account for about 11% of The Bronx’s residents.

Immigration is an important source of its population inflow, with about 34% of its residents being foreign born.

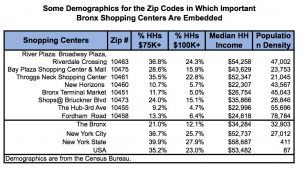

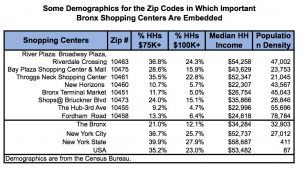

A close look at per capita and household incomes yields some very interesting retail-related results. As noted above, per capita and median household incomes in The Bronx are comparatively very low. If we look a little deeper at the percentages of its households that have annual incomes of $75,000+, 21%, and $100,000+, 12.1%, they are not stand outs. However, if we look instead at the absolute numbers, we see that about 100,000 households have annual incomes over $75,000 and roughly 58,000 households have incomes above $100,000. The $75,000 households are roughly equivalent to all the households in Orlando, FL or Lincoln, NE; the $100,000 households are roughly equivalent to all the households in Syracuse, NY or Savannah, GA. (See the above table). For major retailers, these are not small market segments.

Over four decades, I’ve conducted retail –related market research in places like the Bronx, downtown Brooklyn, and Jamaica Center in NYC; Midtown Elizabeth, the Bayonne Town Center, and West New York’s Bergenline Avenue in NJ. What I have usually found is that the distribution of household incomes contained a substantial number of households that were solidly in the middle income category and many that even were in the upper middle income group. While a minority in number, based on the spending patterns revealed in BLS expenditure surveys, I would estimate that the middle income households accounted for a hefty portion if not most of retail spending in these study areas. However, when you looked at the local stores and their merchandise, it was obvious that the vast majority targeted the low-income shopper. The fact that a number of these low market merchants usually were making out like bandits, with sales/PSF higher than on some prestigious commercial corridors in Manhattan, prevented merchants from refocusing on the area’s solid middle income residents. Consequently, these middle income households were strong “outshoppers,” patronizing more distant shopping centers and districts.

Greater population density not only increases the aggregate spending power of low income households, it also does the same for the middle income households, who, though probably much smaller in number, also probably have much greater spending power.

Many of these middle income residents have strong emotional ties to their friends, neighbors and neighborhoods. Many may be immigrants for whom the cultural ties with their local countrymen may be essential components of their preferred way of life. Consequently, they don’t move.

Also, many may live in solidly middle income neighborhoods that are not on a cliff’s edge of decay and destruction. They may be hardworking members of two or even three or four income households that buy $350,000 homes.

The Major Retailers Now Located in The Bronx

The above table identifies 85 national and regional retail chains, shows those that are now located somewhere in The Bronx, and how many stores, if any, they have there. This list is not exhaustive. Together, the 75 identified chains that have Bronx locations have a total of 290 stores.

Those with no stores are shown to demonstrate the types of retailers The Bronx still has not attracted. Certainly The Bronx is not attracting the likes of Gucci, Prada, Valentino, Tiffany, Duxiana, Ralph Lauren, etc. They are far, far too ritzy and more appropriate for Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, Midtown Manhattan or the Americana Shopping Center in Manhasset, NY. Nor is The Bronx attracting, perhaps thankfully, those like Talbots, Chico’s, Ann Taylor or Banana Republic – many of these apparel chains are fighting for survival. Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods still have stayed away. So has Walmart and its sibling Sam’s Club – due more to strong political opposition in NYC to Walmart than the chain’s lack of interest in NYC locations.

The retail chains that now seem to like the Bronx the most are those that feature strong value pricing in either big box, off-price or factory outlet formats such as Home Depot, BJs, Best Buy, Target, Burlington Coat, Marshall’s, TJ Maxx, DSW, Gap Outlet, American Eagle Outlet, Macy’s Backstage, Nine West Outlet, Aldi, and the recently announced Saks Off 5th. These retailers have honed in nationally on the middle class’s huge number of deliberate consumers who are:

- Much more value conscious

- Cautious spenders and

- Expect big price discounts from retailers.

They are the retailers whose business plans are designed to take advantage of this key feature of retail’s new normal, a feature that is killing or maiming many other retail chains.

Additionally, since 1987, the Bay Plaza Shopping Center and Mall has grown into an almost 2 million SF retail complex. It had a major post Great Recession expansion that has successfully attracted a new 160,000 SF Macy’s as well as numerous specialty retail chains that feel very much at home in middle market retail centers such as American Eagle, Forever 21, H&M, Old Navy, Aldo, Gap, Charlotte Russe, Raymour & Flannigan, Claire’s and Victoria’s Secret. These retailers are all probably targeting shoppers who come from households with annual incomes above the $34,284 that is the median household income for The Bronx. Moreover, the location of this rather isolated shopping center assures that the roughly 50% of Bronx shoppers, who are in households with cars or who can afford using livery cabs, will be its primary patrons.

Also worthy of note is that this shopping center/mall has attracted some of the youth oriented retailers that are now among the most successful in the industry, such as H&M and Forever 21.

Speaking of Macy’s, traditional department stores nationally have been hit very hard by the new normal. Macy’s, for example, has been struggling nationally to develop a viable new strategy by closing under-performing stores, strengthening its e-commerce operations and by developing an off-price chain like Nordstrom’s Rack. Kmart (a part of Sears) has also been struggling and closing stores. JCPenny hit both the brick wall of the Great Recession and a disastrous marketing strategy that halted sales coupons and discounts. Given their stressed situations, one might reasonably have expected these department store chains to have withdrawn from the income-poor Bronx. To the contrary, Kmart continues and it is located in the Bay Plaza Shopping Center, along with JCPenny and the new Macy’s. Even more recently, it was announced that Saks Off 5th, the off-price format of Saks Fifth Avenue, was coming to this mall. Under the new normal, shopping centers and malls anchored by traditional department stores are supposed to be in heaps of trouble, unless they have high end shops supported by lots of affluent shoppers. Nevertheless, Macy’s has also kept its Parkchester store open and located one of its new Macy’s Backstage off-price stores in the Fordham Place development on Fordham Road. According to the owners of the Bay Plaza Shopping Center and Mall , their J. C. Penney and Kmart tenants “are in the No. 1 range for their respective chains” in terms of sales (See: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/13/realestate/commercial/new-york-developers-to-build-suburban-style-mall-in-the-bronx.html ) In summary, while traditional department stores are taking a real licking nationally, those in The Bronx surprisingly seem to be doing well.

The Bronx has long attracted retailers that court lower middle-income and ethnic shoppers. Retail chains, both local to NYC and those with penetration into larger multi-state areas, have developed to service such customers. The Bronx also has attracted other regional chains that serve a broad spectrum of customers. It has, at least, 11 of these regional chains and they have about 53 stores in various commercial districts in the borough. Among these chains are: Jimmy Jazz, Dr. J’s and V.I.M. that specialize in urban wear; the sporting goods chain Modell’s. and the appliance chain PC Richards. Some of these chains have been around for 50+ years – Danice, for example, dates back to the 1930s.

Added to them are a number of national chains that also focus on lower income and lower middle income shoppers and who feel quite at home with locations in ethnic, low income neighborhood shopping districts as well as in more solidly middle income districts:

- Family Dollar, 19 stores

- Dollar Tree, 3 stores

- Payless, 18 stores

- Rainbow Shops, 18 stores

- Gamestop, 14 stores

- GNC, 13 stores

- CVS, 17 stores

- Walgreens, 16 stores.

Retailers having at least a partial focus on the lower income market are less likely to face another major challenge generated by retail’s new normal, e-commerce. Their low income customers are less likely to have Internet connections in their homes and, more importantly, less likely to have the credit cards needed to make e-commerce transactions.

Where Is The New Retail Going?

Are retailers flocking to The Bronx’s old, well-known urban corridors? Not so much. To pedestrian and mass transit oriented locations? Some, but far from most. Or to car oriented shopping centers with large parking lots or large parking garages that are cheek to jowl with major highways? Now, we’re surprisingly on the yellow brick road. Let’s take a closer look and see what I mean.

Are retailers flocking to The Bronx’s old, well-known urban corridors? Not so much. To pedestrian and mass transit oriented locations? Some, but far from most. Or to car oriented shopping centers with large parking lots or large parking garages that are cheek to jowl with major highways? Now, we’re surprisingly on the yellow brick road. Let’s take a closer look and see what I mean.

The Fordham Road Shopping Corridor. With over 300 specialty shops and chains, it has long been The Bronx’s largest shopping district and claims now to be the third largest in NYC. The heart of the district runs about 0.7 miles along Fordham Rd from Jerome Avenue on the west to Washington Avenue on east, across from the Fordham University campus. It’s subway stations are on its western edge, on Jerome avenue and the Grand Concourse, though MetroNorth has a very busy station on the eastern edge at Webster Avenue. Next to it on Fordham Plaza is a very busy bus transfer point.

At Fordham Rd and Webster Ave. Fordham Place on right; Fordham Plaza, a major transportation and commercial hub is back to its left. The MetroNorth station is on the left side of the photo submerged and behind the trees. Photo from Google.

Major auto access is provided on the west by I-87 which is about 0.5 miles from the Jerome Avenue- Fordham Road intersection. On the east its about one mile from Washington Avenue to the Bronx River Parkway and about 3.0 miles to the Hutchinson River Parkway. For delivery trucks, it’s about 0.35 miles farther to I-95. Traffic along Fordham Road can be dense and slow. Finding parking on or near this shopping corridor can be time consuming. AlI things considered, Fordham Road’s highway access might be considered as marginally acceptable.

According to data published by a commercial broker, there are 500,000 people living within 2 miles of the rehabilitated Fordham Place building on Fordham Road at Webster Avenue. The corridor is mainly embedded in zip code area 10458 that has a population density of 78,784, more than double that of the borough. But, its residents are poorer than most Bronx residents; their median household income is about 28% lower than that of the borough. Only about 13% of its households have incomes of $75,000+/yr.

The district has attracted a number of national chains: American Eagle Outlet, Best Buy, Claire’s, Footlocker, Gamestop, Gap Outlet, Macy’s Backstage, Marshall’s, Nine West Outlet, Payless, Rainbow, Sleepy’s, Staples, Starbucks, The Children’s Place, TJ Maxx, Walgreens and Zale’s.

Marshall’s, Children’s Place and PC Richards in the old Alexander’s Department Store building at the key intersection of East Fordham Rd and the Grand Concourse. Photo from Google.

For any solidly middle income residential area, that’s certainly not a tacky mix of shops to have close by. For a dense population with modest incomes, that mix may strike some observers as surprisingly robust. There are a lot of strong, very reputable chains among them, and many that have a value pricing strategy that is very successful under the new normal. The attraction of a Best Buy, TJ Maxx and a Macy’s Backstage is particularly impressive. Best Buy and Macy’s Backstage now occupy a space that once was a very large Sears store. Marshall’s, now in the former Alexander’s building, has long entered low income, ethnic commercial districts, but its sister chain, TJ Maxx has, to my ken, been somewhat pickier.

A number of these chains have clustered in two relatively large buildings, the former Alexander’s and Sears department stores, that are near mass transit assets and as close as a location in the district allows to a major highway, e.g., either I-87 or the Bronx River Parkway. However, for delivery trucks, traveling east from and back to I-95 have an extra 2.3 mile trip. Both buildings also have public garages nearby.

Could other value-pricing chains find locations in this district interesting? Those with small space requirements, perhaps, and then they would want to be very close to other national chains. More of the flailing national specialty retail chains soon may be opening their own factory outlet stores and bringing them to all sorts of shopping centers. Gap, Nine West and American Eagle have such stores in The Bronx. There’s a Gap Outlet in Jamaica Center, Queens, NY. Banana Republic just turned its decade old store in the well regarded Austin Street shopping corridor in Forest Hills, NY into an outlet format. This trend, if it gains momentum, augurs well for retail recruitment efforts, not only on Fordham Road, but for many other lower income ethnic shopping districts.

The situation is far more problematical for those value pricing chains with large space requirements, say 25,000+ SF. I doubt that there are any more old department store type spaces left in the Fordham Road district, so there would have to be parcel assemblage as well as new construction. In NYC and many other major cities, that often can be very difficult and expensive to do. Also, retailers that need large spaces probably are hoping to penetrate a larger market area from which shoppers arrive in cars. For them, having a major highway close by is a major requirement, as is a copious amount of parking. That, for example, has been the scenario for new retail projects along Broadway in the Kingsbridge section of The Bronx.

The Hub. This intersection of 149th Street, Third Avenue and Melrose Avenue has been an important retail district for South Bronx residents since, at least, the 1930s. Today, it is more of a strong ethnic neighborhood commercial district than a downtown.

The first Alexander’s department store was opened there, but it was the chain’s second store on Fordham Rd and the Grand Concourse that really put it on the map. Today, The Hub has many of the national chain stores that are found in many lower income ethnic shopping districts: Ashley Stewart, Carters Baby & Kids, The Children’s Place, Game Stop, GNC, Kids Footlocker, Lids, Payless, Rainbow, Sleepy’s, and Walgreens. It also has the regional and local chains that feel very at home in such districts: Cee-Cee, Danice, Dr. Jay’s, Dr. Jay’s Ladies, Jimmy Jazz, Modell’s, Porta Bella, S&A Stores, and Youngland.

The Hub is in zip code area 10455, which has a population density of 55,696. That’s 69% higher than The Bronx’s population density and 106% higher than the population density of New York City. The area’s population is also relatively poor, with a median household income of $22,996/yr. That is 32.9% lower than the median household income of The Bronx and 56.3% lower than that of NYC.

The district’s mass transit assets are the #2 and #5 trains that serve its 3rd Avenue-149th Street station and three bus lines the BX15, BX19, and BX2.

I-87 is about 0.69 miles away to the west and 0.72 miles away to the south. I-278 is about 0.94 miles away to the east.

The development of the Bronx Terminal Market (see the discussion of that shopping center below), just 0.75 miles away as the crow flies, has inserted a very powerful competitor into The Hub’s trade area. While that shopping center may not be all that easy to get to, it’s strong mix of retailers should still be a heavy-duty magnet for many residents in The Hub’s trade area. Concourse Plaza, a very troubled shopping center on 161st Street, is about 0.67 miles away as the crow flies. It’s talked about rehabilitation could inject another serious competitor into the Hub’s trade area.

The former Alexander’s building in The Hub, which had been occupied by a Conway’s and a mini-mall, was sold fairly recently. Local newspapers report that a search is on for a major, higher quality retail tenant to occupy that space. One may wonder if that is really possible in a retail world where major chains have become even choosier about potential new store locations than they were a decade ago. Yes, aggregating the spending power of low income households in dense urban areas like the South Bronx can attract some retailers, but there are also obvious limits to how many national retailers will be attracted and their quality. This is especially true when strong competing shopping centers have opened nearby. An effort to create a strong base of ethnic oriented small retailers and small chains might be a more viable growth strategy for the area.

Bay Plaza Shopping Center & Mall.

I’ve already written above a lot about this retail complex. I’ve combined the mall and the shopping center into one entity, because that’s how I think most of its patrons see them. Below are some additional points that I believe have more general application to retailing in other urban areas similar to The Bronx.

In the heart of a very densely populated and poor county, this shopping complex is very traditional, very successful and has a very suburban-type location and feel. It is situated in the geographic arm fold of two major highways, I-95 and the Hutchinson River Parkway. (See the above map). It is very oriented to shoppers who travel by car. Even though it is close to the densely populated Coop City, the “Hutch” is an effective pedestrian moat. Bay Plaza functions very much like an suburban mall of the 1980s, which was when it was started, and it probably draws from southern Westchester County. It is embedded in zip code 10475 that has a population density 27.8% lower than that of The Bronx, while its median household income is 27% higher. About 29% of its residents come from households with incomes over $75,000/yr; that percentage for The Bronx is only 21%. Most of the new and successful retail shopping centers that have developed in The Bronx over the last 15 years are located in neighborhoods with above average incomes that have very good highway access. Such access is important for two reasons: to attract shoppers and for making store deliveries fast and easy. In The Bronx and other parts of NYC, the latter is more important than most folks might expect. The visibility of their buildings and signage is another important factor.

This retail complex has had the same ownership entity since it was created in the late 1980s. It has grown significantly in size over the years and has about 150,000 SF of office space associated with it. The owners plan to add several thousand residential units in the future, thus making this complex much more like a town center type mall. In the past, the owners have displayed prudence in their expansion efforts.

Their approach to attracting retail tenants is heterogeneous compared to other mall operators. Their tenants can range from traditional department stores (e.g., Macy’s) and specialty retail chains (e.g., Victoria’s Secret) to the value pricing department stores (Marshall’s and Saks Off 5th) and retail chains (DSW). Also included are several regional chains such as Easy Pickins and Jimmy Jazz. Importantly, they have also attracted retailers who are big hits with teens and young adults, such as H&M, Forever 21, and Hot Topic. This retail complex has every type of retailer that is doing well under the new normal.

My guesstimate is that this retail complex probably has annual sales in the $1 billion to $1.5 billion range. Given that guestimate and its strong highway access, it seems probable that it is also drawing significant numbers of shoppers from outside of The Bronx. Not bad for a major retail complex located in the poorest county in NYS!

This retail complex, together with the Hutchinson Metro Center and the Throggs Neck Shopping Center, are adding new luster to business locations along the Hutch in The Bronx. They are quickly noticed by any observant passing auto passenger.

The Broadway Corridor in Kingsbridge between about 225th Street (Target) and 238th Street (BJ’s). Photo from a Ripco brochure for Broadway Plaza

The Broadway Corridor in Kingsbridge. As can be seen in the photo above, this 13 block long corridor backs on to the Major Deegan Expressway (I-87) and Exit 10 is in its midst. This area is serviced by three stations for the #1 subway line. It is embedded in zip code 10463 that contains parts of the Kingsbridge and Riverdale neighborhoods. This zip code, too, is densely populated, 47,002 persons per SqMi. That’s about 43% higher than the borough’s population density. It also has a median household income, $54,258 that is 58% higher than the borough’s. Its rate of households with incomes of $75,000+/yr, 36.8% and $100,000+/yr are very substantially above those for The Bronx and about equal to that of NYC.

The corridor saw the construction of three major shopping centers in 2004, 2014 and 2015 that totaled about 530,000 SF. Their insertion into this dense, mature neighborhood and how they mesh visually and functionally with their surrounding urban context deserves its own major discussion. Added to such a discussion are several retail projects in Queens and Brooklyn that have been built in the past decade or so.

A view of part of River Plaza along W225th Street. Photo from Google.

The first and largest was the 235,000 SF River Plaza. Target is not only a major anchor store, it also was a co-developer of the project. Other major tenants today are Marshall’s, The Children’s Place, Lane Bryant, Payless, Applebee’s and Planet Fitness.

Target expected to draw from a trade area population of about 400,000, according to Paul Travis, who played a lead development role on the project. Target also expected that some of these customers formerly traveled to Target stores in Yonkers or New Jersey. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/15/business/target-gives-new-look-to-the-bronx.html .

The project was built on a 9.5 acre site that was formerly a decayed hospital warehouse, along with some car-repair shops, tire stores, and a fried-chicken restaurant. Because of the size of the Target store, it was built so the vast majority of its space is below grade to meet zoning regulations. It’s roof provides surface parking. The project’s tenants reportedly have had very strong sales numbers.

Most probably because of the Great Recession, it took about 10 years for Broadway Plaza, the second significant project in the corridor, to open. It has 133,000 SF and is tenanted by TJ Maxx, Aldi, Party City, Bob’s Furniture, Forever 21 and Blink. Bob’s Furniture replaced the bankrupt Sports Authority.

It was built on land that was mostly a former municipal parking lot that sits right by Exit 10 of the Deegan Expressway and close to an elevated subway station.

It was followed in 2015 by the 162,000 SF Riverdale Crossing. Its major tenants are BJ’s, Petco, Smashburger, Buffalo Wild Wings, CityMD and Chipotle. It, too, has substantial portions of its structures underground and a lot of rooftop parking. It was built on a property that formerly was a factory for the Stella D’Oro Biscuit Company. Interesting to note that its developer made the following point to the press: “… its location next to the Major Deegan Expressway, allows for major deliveries and loading, as well as prime signage opportunities.”

The developer of this project ,Metropolitan Realty Associates LLC (“MRA”), has an interesting investment strategy: “specializing in opportunistic and adaptive reuse investments.”

Dart Westphal, a longtime Kingsbridge resident with 25+ years of experience in the urban economic development field, had some interesting observations about what is happening to his neighborhood’s retail:

“The longstanding assumption that the heavily populated Bronx was ‘under-stored’ has resulted in three ‘malls’ being developed. One at 225th Street is anchored by Target. A second at 230th street now includes Bobs furniture as well as Aldi and Party City. And a third at 238th Street includes BJ’s warehouse, Buffalo Hot Wings and other eateries like Chipotle, Smashburger and Subway.

The area near the 231st Street #1 line train stop has long had a substantial local retail presence. Staples and Stop and Shop are nearby at 234th Street. But recently there has been an interesting increase in more upscale offerings. The Bronx Ale House is perhaps the first development to raise eyebrows. Denizens say things like ‘who would have thought beer snobbery would come to the Bronx’. Reportedly beer distributors had a much easier time selling craft brews to the local grocers after the Ale House opened. Other independent eateries have moved in and Buffalo Hot Wings hasn’t hurt the Ale House’s business – they are expanding for the second time.

A second location is the ‘Garden Gourmet’. It is the sort of upscale grocer with lots of prepared food and fancy choices that appears in many parts of NYC, but has until recently been absent in the Bronx.

These developments have meant a wide range of options for shoppers. Target and Aldi at the discount end and Garden Gourmet at the premium end. And the Appleby’s at the Target Mall was as crowded as the Ale House on a recent Saturday after the nearby Columbia-Cornell football game.

It would appear that the combination of a big underserved mass market and a little recognized group of customers willing to pay a premium are driving a retail boom in Kingsbridge, the Bronx.”

The New Horizons Shopping Center and The Bronx Terminal Market. What these two projects have in common is that neither probably would have happened if local politicians or neighborhood community development activists had not pressed hard for them.

The New Horizons Shopping Center location as shown on Google Maps

Back in 1974, the Crotona Park East section of Bronx had been decimated by “overwhelming incidents of arson, disinvestment, abandonment and population loss.” This led to the formation of The Mid Bronx Desperados (MBD), one of the borough’s most effective and respected housing and community development organizations. Working with LISC, MBD was instrumental in the creation of the 133,000 SF New Horizons Shopping Center that opened in 2003 in its neighborhood. This shopping center, most importantly, brought in a major supermarket chain, Pathmark. Today, a Stop & Shop has taken Pathmark’s place and the center’s other tenants includes Auto Zone, TJ Maxx, Footlocker, Petland, Game Stop, Subway, IHOP and Taco Bell.

The site of the shopping center was previously targeted by the City to provide new and modern spaces for small manufacturers. They never appeared, so MBD and LISC cleverly steered the city to a major neighborhood retail use.

New Horizons is located in zip code 10460. It has a population density 32% above that of The Bronx and a median income that is 35% below the Borough’s. It has very few households with incomes above $75,000. Yet this is a traditional suburban type, car oriented shopping center, with shops located in a sea of parking spaces. It is also very close to the Cross Bronx Expressway. (See map below). This is not an urban shopping project with a solid wall of shops on the ground floors of buildings that abut and open to sidewalks. On the once infamous Charlotte Street, MBD had previously built ranch style single family residential units. Their occupants have well tended backyards, some boats sitting in driveways and some above-ground swimming pools. Given their MBD origins, both the housing and the shopping center certainly reflected local aspirations and needs. Many other dense, low-income, ethnic urban areas may also aspire to more suburban type retail projects. Because people are less affluent does not necessarily mean they like downtown or other urban retail environments.

The Bronx Terminal Market (BTM) is a 913,000 SF retail complex that opened in 2009, despite the Great Recession. It is owned and operated by the Related Companies, one of the largest real estate developers/owners in the USA. The new Yankee Stadium also opened in 2009. A coincidence? I think not. With the new stadium, political leaders and the Yankee organization wanted the surrounding area improved. Metro-North put in a new station, existing subway stations were improved and the BTM was built.

The BTM site, located south of the Stadium, with the vehicles on the Major Deegan Expressway roaring by right next door to the west, has had a long struggle to find its best use. It was the location for the Bronx House of Detention and a public market that morphed into a market for fruit and vegetable wholesalers. In 1990, Regional Plan Association’s report found it to be a prime location for future retail development. Unfortunately, its ownership struggled in vain for years to get a project going. Related finally gained possession in 2004. Construction started on the current market in 2006, the same year that construction for the new Yankee stadium started.

Today, the BTM is akin to a retail power center on steroids with a tenant list that includes: Babies R Us, Bed, Bath & Beyond, Best Buy, BJ’s, Burlington, Gamestop, Home Depot, Marshalls, Michael’s, Raymour & Flannigan, Target and Toys R Us. That’s one powerful retail line up! It needs to draw from a very wide and densely populated trade area, one that probably goes well beyond the South Bronx.

The BTM has strong auto and mass transit assets that enable it to penetrate a large trade area. It is served by the 149th Street-Grand Concourse subway station, with its 2, 4 and 5 trains, as well as the 161st Street-Yankee Stadium station, served by the 4, B and D lines. It is also a short walk from the Metro-North station at East 153rd Street. A number of bus routes serve the BTM. Importantly, it also can be accessed by car from three exits on the Major Deegan Expressway. To go with them, it has a very expensive to build six level garage with 2,600 parking spaces. That much parking suggests that the project’s planners expected about 70% of its customers to come by car.

The BTM is embedded in zip code area 10451 that has a population density 37% higher than the borough’s, while its median household income is 22% below that of the borough’s. This close-in population density is not why this shopping center is where it is, though the nearby households with modest incomes probably benefit significantly from having such an array of value price retailers in their neighborhood.

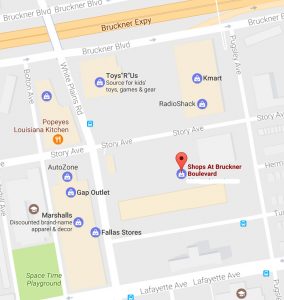

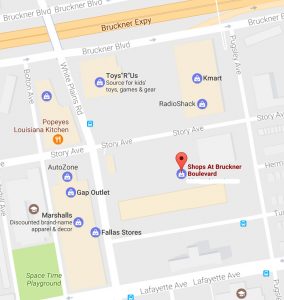

Throggs Neck Shopping Center and the Shops Bruckner Blvd. Both of these shopping centers are in the southeastern part of The Bronx and rather distant from any subway lines. Throggs Neck Shopping Center is 1.8 miles from the #6 line’s Parkchester station; the Shops at Bruckner is about 0.8 miles from the #6 line’s Westchester Square – E. Tremont station. However, each is within a few hundred feet of a major highway.

The 300,000 SF Throggs Neck Shopping Center in the Ferry Point section of The Bronx was completed in 2014. The property had been used as a USPS equipment transfer station, but had been vacant since 2010. It is located in zip code 10561 that has a population density about 34% lower than that of The Bronx, while its median household income, at $52,347, is about 53% higher. About 35.5% of its households have incomes above $75,000/yr; about 22.8% are above $100,000/yr.

Its tenant mix includes a large Target that had to be built below grade as well as TJ Maxx, Sleepy’s, Famous Footwear, Skechers, Petco, Five Guys, Applebee’s, Chipotle, Subway and Starbucks.

The entrance to Target’s 165,000 SF below grade store in the Throggs Neck Shopping Center in the Ferry Point neighborhood of The Bronx. Below grade spaces are a way for developers to get around zoning rules aimed at keeping big box stores away.

It is easily accessible from the Hutchinson River Parkway, from which it is visible. It has 650 free parking spaces, many of which are located on the Target’s roof.

The Shops at Bruckner Boulevard Shopping Center is next to the Bruckner Expressway and appears to occupy four city blocks.

The Shops at Bruckner Blvd was built back in 1996 by Forest City. Here is how this developer sees itself:

“Forest City is a pioneer in bringing larger-format retailing to urban locations, primarily in the New York City metropolitan area, previously under-served by major retailers.

With high population densities and disposable income levels comparable to the suburbs, urban development is re-emerging as an opportunity for retailers….” http://www.forestcity.net/properties/shop/urban_retail/Pages/default.aspx

In NYC, Forest City also “owns and operates Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn, Queens Place in Queens, and Harlem Center in Manhattan.” They all feature large format retailers.

As far as I have been able to discern, the tenant list at The Shops at Bruckner Boulevard includes: Auto Zone, Babies R’Us, Carters, City Jeans, Conway, Danice, Fallas Stores, Gamestop, Gap Outlet, Jimmy Jazz, Kmart, Marshalls, Modell’s, Old Navy, The Children’s Place and Toys R’Us.

This shopping center is located in zip code 10473 that has a population density of 26,846, about 18% below the density level of The Bronx. While the median household income in this zip code is only about 5% higher than that of The Bronx, its percentage of households with incomes over $100,000/yr is 25% higher than the borough’s.

Some Take Aways

The Current Status of Retailing in The Bronx:

- The Bronx has undeniably made very significant progress over the past two decades. What some may find surprising is that one of the most visible improvements is the much larger number of strong and desirable national retail chains it has attracted. My best efforts identified 75 national and major regional chains that have Bronx locations and a total of 290 stores. There may be more.

- There can be little doubt that its residents now have a much wider range of choice among desirable retailers.

- This is not only true for the low and lower middle income shoppers, but also for consumer in the borough’s more affluent households that have incomes of $75,000+.

- Very importantly, the borough is attracting, in strength, the types of retailers that are flourishing today under retail’s new normal. They promise to continue to thrive well into the future. Included in this group are those that follow a value pricing strategy such as TJ Maxx, Marshalls, Burlington Coat, Ross Stores, Nordstrom Rack; low-price, fast fashion operations such as H&M, and current teenager favorites such as Forever 21 and Hot Topic.

- In order to survive, many department stores (e.g., Nordstrom, Saks, and Macy’s) have opened “off-price” types stores and specialty retail chains (e.g., Gap, Old Navy, Banana Republic, American Eagle, Nine West, and Ann Taylor) have opened “outlet” type stores that are not in outlet malls. More department stores and specialty retail chains can be expected to follow suit. The Bronx has already attracted a number of them and it can be expected to attract more in the future, if this trend holds.

- The Bronx has been particularly good at attracting large format retailers such as Target, BJ’s, Best Buy and Home Depot, though many others have not yet appeared, including Walmart, Lowe’s and Costco.

- The Bronx is filled with the “deliberate consumers,” whose more cautious spending is a key characteristic of the new normal that today’s retailers must face. The low-priced and value priced retailers that The Bronx has attracted are best positioned to, in turn, attract the hard to win expenditures of the deliberate consumers.

- Moreover, because the borough long has been so badly understored, some types of retailing that are struggling in other geographic areas are finding surprising traction in The Bronx. For instance, some department stores in The Bronx appear to be flourishing, while this category is tanking elsewhere in the nation. It also has attracted some specialty retailers such as Michael Kors and Victoria’s Secret, while many chains in that category, including Kors, are struggling for survival in other locations.

Where Did It Happen?

- One might think that retail growth in such a densely populated county would go primarily into very urban types of commercial spaces, e.g., ground floors and lower stories in rows of adjoining buildings that hug and open onto sidewalks. I looked at 10 shopping centers/districts. The two oldest, Fordham Road and The Hub, have that kind of urban retail spaces. The others, the shopping centers, were very car-oriented and suburban in design. All also were located very close to major highways and had copious amounts of on-site parking.

- This was even true for the New Horizons Shopping Center that was built through the efforts of the MBD and LISC to serve customers who, on average, have very modest incomes.

- It is interesting that Target did not locate one of its small format stores in the Bronx. They are intended for tight urban districts. All three Target stores in The Bronx are over 100,000 SF and close to a major highway.

- Some of these shopping centers, such as River Plaza, have some interesting design characteristics as they try to squeeze large format stores into tight, mature and dense urban contexts.

Why Did It Happen?

- The Bronx has been attracting some important and experienced developers: e.g., The Related Companies, Forest City, Washington Square Partners, MRA. These developers feel thoroughly at home in dense urban environments, even those dominated by ethnic, lower income households. Many also share Forest City’s view that these urban areas have been understored though they have “high population densities and disposable income levels comparable to the suburbs.” Many also share MRA’s investment strategy of “specializing in opportunistic and adaptive reuse investments.”

- The Bronx certainly has the low income population density Michael Porter cited as a redevelopment asset. It is the third densest county in the nation and the poorest county in NYS. In the past, this market segment had been badly underserved locally.

- Less noticed, however, have been the borough’s roughly 100,000 households that have annual incomes over $75,000 and roughly 58,000 households with incomes above $100,000. The Bronx’s $75,000/yr households are roughly equivalent to all the households in Orlando, FL or Lincoln, NE; the $100,000/yr households are roughly equivalent to all the households in Syracuse, NY or Savannah, GA. These residents did a lot of “outshopping” to retailers outside of The Bronx. Most of the new shopping centers are situated close to where significant clusters of these more affluent households are located. Some developers and major retail chains apparently have noticed these households.

- The Bronx’s major highways, even Robert Moses’s abomination, the Cross Bronx Expressway, have been key assets for attracting savvy developers interested in retail projects. These roads allow the retailers to tap shoppers in the large trade areas they need, even shoppers who live outside of The Bronx.

- The Bronx — as is true for many other low income, dense urban areas – has a lot of “soft” properties ready to be redeployed for higher and better uses. It also had some public land, such as parking lots, that could be redeveloped. Some developers were very crafty/innovative in the way they utilized these soft properties.

- In my opinion, the borough’s political leaders and many of its neighborhood leaders have often played very positive roles in getting these retail projects done. They heard and tried to respond to residents’ grumbles about the poor retail choices available to them.

Implications For Other Dense, Low Income Districts and Neighborhoods. The above discussion of retailing in The Bronx suggests the following:

- Most of the retailers who are succeeding under the new normal are very probably willing to consider locations in a district or neighborhood like those in The Bronx. These can range from the large format retailers to the specialty retailers that have smaller outlet formats.

- Population density is definitely an asset, but don’t just dwell on your low income residents. Also identify and market the households with incomes over $75,000 that may be in your trade area. In a growing number of neighborhoods, ethnic populations are not poor, but solidly middle income or even upper middle income.

- If there is a major highway running through your district or neighborhood, sites near it can be very strong assets.

- Identify and cultivate real estate developers who have done major retail projects in neighborhoods or commercial districts similar to yours. Not every developer will fall into this category, but many will!

- Learn from them about the types of sites and opportunities they are looking for.

- Be open to retail centers that have a car-orientation. At least, here in NYC, and I suspect in a lot of other large urban areas, residents not living in the downtown core are likely to use mass transit to commute to and from work in the core, but then to prefer either walking or using their cars when shopping for comparison shopping type goods. This is true even for folks with modest incomes, as long as they have a car. Of course, this is especially true when subways or commuter rail are not present.

- Large ethnic downtowns are already usually beehives of activity with high pedestrian counts. But, they are also congested with vehicular traffic, often on a main drag that has an old, narrow road bed. They are often comparatively far from major highways. These downtowns need to address such traffic problems. That’s heresy, I know, and I’m a strong advocate of transit oriented development. However, as long as the residents of a downtown’s trade area find it much easier to drive and park at other shopping centers than in the downtown, those residents probably will be doing a whole lot of outshopping. That is a statement of fact, not value.

- Finding appropriate spaces for large format retailers will be another key to their entry into large ethnic downtowns. Their leaders would be wise to have soft properties identified that could be redeveloped for such tenants. The large format retail stores in Kingsbridge’s Broadway Corridor show that they do not need to have massive amounts of space on a main drag to be successful, if they still can have adequate visibility. That might ease their insertion into places like Fordham Road and Jamaica Avenue in Queens. Still, inserting large format stores into dense urban contexts while maintaining their walkability and capacities to stimulate social interactions is a challenge that needs much more analytical and design work. Ideological stances against large format retailers have prevented the discussions that are needed about this issue.

- On the other hand, the outlet formats of specialty retailers can be good recruitment prospects for such downtowns. They’ll have much smaller space needs and a lot of them sell merchandise that is easier to carry on mass transit.

- However, to rely solely on the outlets will probably substantially limit a downtown’s retail growth potential. In turn, that may be what these ethnic/minority downtowns have to do. In that case, building up their Central Social District functions will become even more essential for incerasing their vibrancy and magnetism.

Are retailers flocking to The Bronx’s old, well-known urban corridors? Not so much. To pedestrian and mass transit oriented locations? Some, but far from most. Or to car oriented shopping centers with large parking lots or large parking garages that are cheek to jowl with major highways? Now, we’re surprisingly on the yellow brick road. Let’s take a closer look and see what I mean.

Are retailers flocking to The Bronx’s old, well-known urban corridors? Not so much. To pedestrian and mass transit oriented locations? Some, but far from most. Or to car oriented shopping centers with large parking lots or large parking garages that are cheek to jowl with major highways? Now, we’re surprisingly on the yellow brick road. Let’s take a closer look and see what I mean.

Women’s Apparel Shop in Downtown Great Barrington, MA

Women’s Apparel Shop in Downtown Great Barrington, MA