By N. David Milder

Since 2008, I have been writing about the New Normal for our downtowns. Recently, I have been asked on several occasions if I had a relatively brief summary article. I didn’t, so it seemed the time to write this one.

Downtowns Are Now Expected To Succeed

Success stories abound everywhere you look. Not every downtown has made it, but many have, and many more are well on their way. Today, laggard downtowns really stand out.

Downtowns Are The Place To Be

Today, lots and lots of people seem to want to be downtown, not to flee or avoid it. They are easily attracting people to visit, work and, especially, live. Importantly, this is increasingly happening organically. That’s a significant paradigm shift from a few decades ago.

In fact, downtowns have become so popular that many are now facing problems of high pedestrian congestion and how to get all these people in and out of the downtown quickly, comfortably and affordably via mass transit, vehicles, bikes and on foot. Success does not always mean the end of all problems; sometimes it brings along its own set of new ones.

The Negative Impacts of the Fear Of Crime And Actual Crime Rates Have Diminished Significantly

Downtown streets at night are less likely to be empty and fear-inducing.

In most large cities, crime and the fear of crime have fallen so significantly that they have fallen out of sight as an issue. There are several strategies that appear to be effective. However, drug use and drug trade induced crime has increased dramatically in many smaller and more rural communities.

Our Ability To Revitalize Downtowns Has Vastly Improved Since The 1980s

We may not be able to solve every problem, but we have a lot of real knowledge about how to revitalize and manage downtowns. Moreover, we now have in many places the professionally staffed organizations to use that knowledge, e.g., BIDs, SIDs, Main Street organizations.

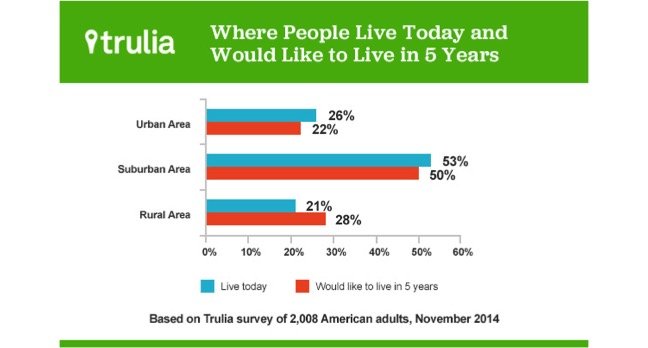

Downtown Housing

Most downtown leaders and experts would agree that the development of significant amounts of market rate housing has been the most important force in successful downtown revitalization efforts. Housing placed in walkable urban contexts, especially near downtown workplaces, has sparked large district revivals. Housing near commuter rail and subway stations also have helped power suburban downtown and neighborhood district revivals away from the urban core.

Mixed use housing in downtown Cranford, NJ

Since the Great Recession, new condo and coop projects have been eclipsed by new rental projects in many downtowns as a result of changing consumer preferences and the impacts of “deliberate consumer” behaviors.

In many medium-sized downtowns, retail has become a less viable component for mixed-use projects because of the reduced demand for retail space and the retail chains’ greater preference for proven locations.

Market rate downtown housing seems more and more to be only for the affluent and very wealthy. As a result, projects with “micro-units” are being built to provide an affordable solution.

Will downtowns stop being everyone’s neighborhood? In the 1970s and 1980s, many feared downtowns were destined to house only our poorest, most disadvantaged residents. Now, will they be ghettos of the wealthy? Should policies be put in place to assure economic diversity in our downtowns?

Nevertheless, the value and viability of downtown housing as a growth engine continues.

Deliberate Consumers

These consumers display much more deliberation about their expenditures than their pre-2008 counterparts, are much more liable to be concerned about needs than wants and tend to focus on a product’s price, quality and/or value. Many have come to expect steep discounts.

They include the vast majority of middle income households, especially those whose incomes have not increased meaningfully for many, many years. Also, this behavior pattern is seen even in customers of luxury markets, where about 30% of the sales are “off-price.” Economic recovery seems to have increased consumer expenditures somewhat, but the cautious consumer decision-making seems to have continued on in full force.

These consumers are everywhere, careful, want their money’s worth, and are here to stay.

E-commerce

Though more than 90% of all retail sales are still in traditional brick and mortar stores, e-retail sales for specific lines of GAFO merchandise have passed 25% to 50%. If current trends hold, they will pass those levels in several other merchandise lines within a few years. But, e-retailing’s biggest impact comes through how it has changed consumer behavior. Most Americans now make an online product and store search before shopping in traditional shops. They browse less inside shops and more often go directly to the merchandise they want and then leave after a purchase. They use smartphones inside stores to find competitive prices online. Some pay with their phones.

It is highly unlikely that brick and mortar shops will disappear. The vast majority of Americans still prefer shopping in them to shopping online. Even online born retailers – e.g., Amazon, Warby Parker — are also opening brick and mortar stores because they see potential benefits resulting from customers being able to use both channels together.

Nonetheless, traditional retailers have to change their business formulae to better integrate the internet into their brick and mortar operations. This probably means that their legacy stores will become less important in the initial stages of the retail sales transaction process, though often more important in the later stages. They will have to take on new functions like pick up points for online orders, storage for quick local deliveries of online purchases or the venues for special attention and pampering for customers filtered out by retailers for making significant online purchases and how they navigated the store’s website.

Retailing In Various Types Of Downtowns

The emergence of deliberate consumers, the growing power and influence of e-commerce and the prior building of too much of retail space have combined to create large upheavals in the retail industry. Retailers are looking for fewer and smaller new spaces in very low risk locations where other retailers are doing really well.

Different kinds of downtowns have been impacted in different ways and to varying extents by the Great Recession. Here are some examples:

- Districts with large luxury markets came through the Great Recession the least scathed and recovered the fastest. Their wealthy shoppers had the best recovery to pre-recession spending levels. Their luxury retail chains benefited from a growing global luxury market and were consequently financially better able to absorb any sales downturn in the US market

- Very small towns with populations less than about 2,500, were among the least hurt downtowns because they had few if any national chain stores. Their retail prospects improved as the incomes of their deliberate consumers recovered

- Many towns in the 15,000 to 35,000 population range have seen their malls badly falter or completely fail as their anchor department stores (e.g., Sears, Kmart, JCPenny) and specialty retail chain tenants closed.

- These retail failures have created an opportunity for many small GAFO merchants to open and do well. The e-retailers and the local mass market merchants like Walmart, Target and Best Buy did not capture all of the market share that the closing department stores and specialty retailers had disgorged. The mass market retailers are typically also ignoring that disgorged share for the small retailers to capture by not increasing their presence in these towns, .

- GAFO retailers in towns in the 2,500 to 15,000 population range also seemed to benefit from these closings. Their local trade area residents previously typically outshopped for GAFO merchandise in the struggling/closed malls

- As many commercial districts in The Bronx, NY, have shown, moderate income ethnic downtowns and neighborhoods are attracting retailers under the new normal to the degree that they can accommodate the often very large space needs of the value oriented and off-price retailers, e.g., Target, Best Buy, Marshall’s and TJ Maxx. Sometimes this means the “factory store” or “outlet” formats of some very highly regarded chains such as GAP, Banana Republic, Ann Taylor and Nine West. Fitting the large format value retailers into these downtowns so as to retain their walkability and scale is a critical urban design issue. Unfortunately, too often the project solutions have been damaging or half-thought through.

- Many downtowns in affluent suburban communities with large numbers of well-regarded specialty retailers, have seen many of them close. Among them were chains such as Chico’s, Coach, Eileen Fisher, Gap, Talbot’s and Ann Taylor. In many instances, the closed stores had under average sales for their chains. This made them vulnerable when their brand encountered strong sales headwinds nationally. In some instances, the stores’ subpar sales were due to more cautious spending by local shoppers. In others, the chain’s merchandise did not mesh with local lifestyles. For example, one expert has noted that Chico’s shoppers nationally had basically “aged out.” In any case, these downtowns are now faced with an unusually large number of vacancies of relatively large spaces that are located in highly desirable locations. They need a strategy to fill those space that will also maintain the strength and attractiveness of the downtown. A viable strategy for maintaining the downtown’s strength may have to look at non-retail uses, as well as subdividing large spaces.

Office Functions and Development

How firms now use office space has drastically changed, influenced by practices at successful high tech firms. With that change, many firms, large and small, are now looking for open spaces for “hot desks.” They have few if any private offices and are configured to stimulate worker interaction and cooperation. They are also using less office space per worker, because the workers are spending more time telecommuting from home or being out with clients.

Consequently, overall demand for office space is being constrained, while on the supply side many of the older downtown buildings are badly out of date and unmarketable. New or adaptively rebuilt downtown office buildings are needed that are configured for the no-office, hot-desk, interactive work environment. Many of the dated office building are either being torn down or converted into residential buildings.

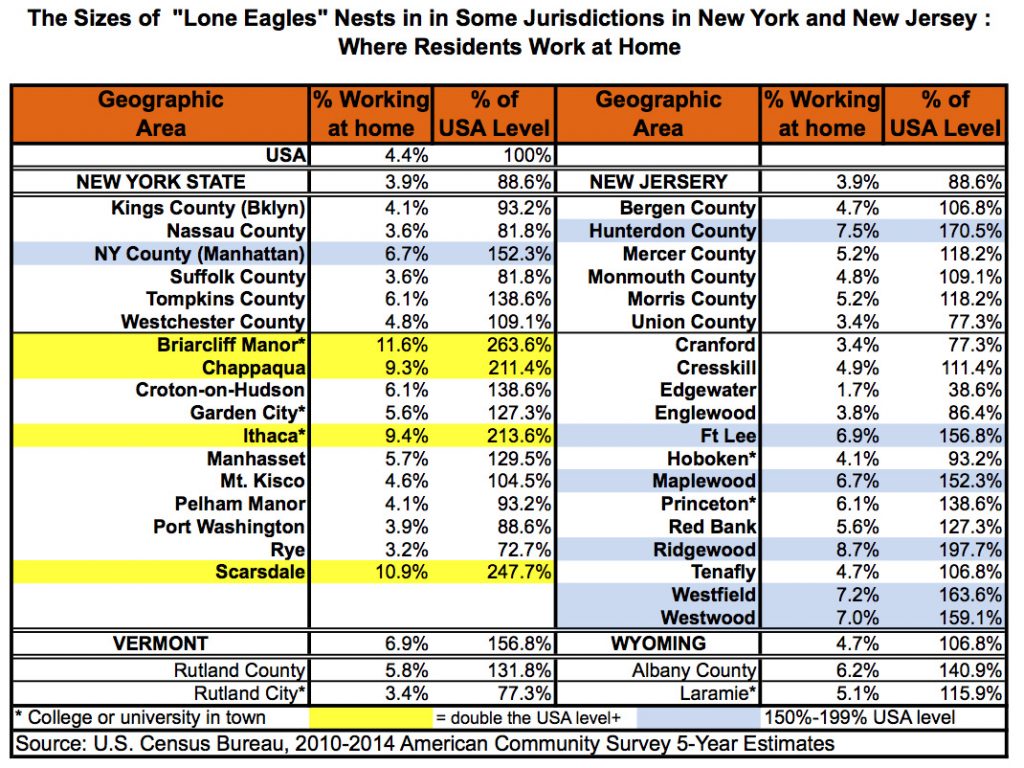

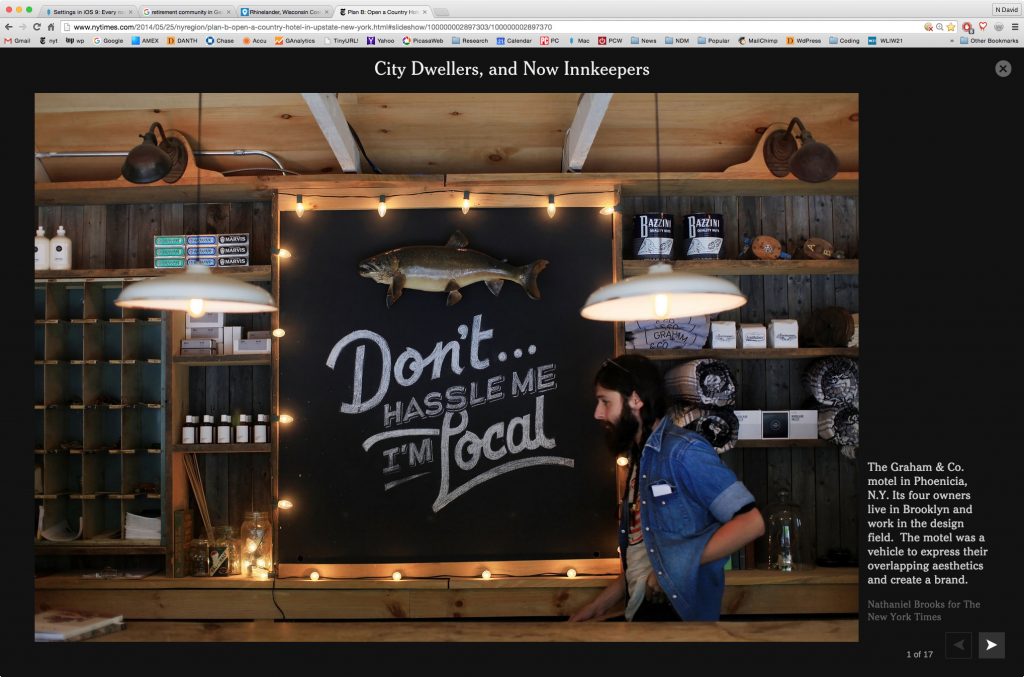

Here and there, usually organically, but sometimes according to a plan, downtown office spaces are being used to stimulate new businesses. This trend is manifested in business incubators, co-worker spaces and buildings geared for start ups. Given the steady growth of the nation’s contingent workforce, many downtowns – be they urban or rural — may find significant economic growth if they can attract and nurture local contingent workers. However, to do that will likely require the presence of several kinds of county or regional level support programs.

Central Social Districts

Since antiquity, successful communities have had vibrant central meeting places that bring residents together and facilitate their interactions, such as the Greek agoras and the Roman forums. Our downtowns long have had venues that performed these central meeting place functions, e.g., churches, parks and public spaces, museums, theaters, arenas, stadiums, multi-unit housing, etc. They are all essential elements of the downtown’s Central Social District (CSD).

Greatly strengthened CSDs have been another important factor associated with the emergence of strong and popular downtowns. In an increasing number of downtowns, their CSD functions have become more important than their traditional CBD functions, e.g., retail and office based activities. Today, for most downtowns, be they large or small, their revitalization strategies must focus on strengthening and growing their CSD’s elements.

The housing element has been discussed above; here are some comments about other important CSD elements:

Formal Entertainment Venues. These include such venues as museums, PACs, concert halls, stadiums, and arenas. They often are held in great esteem within their communities and especially among the local social, business and political elites. However, they also tend to be relatively expensive to build, maintain and operate. Many are venues for types of arts events that have suffered significantly decreased attendance in recent years. There have been a substantial number of failures among these venues and a much larger number that struggle financially each year because their true costs for each admission cannot be sustained by their ticket prices. They consequently need to constantly ask for lots of donations and grants to remain solvent. Too often, it is not a sustainable business model.

Many of them are seriously underutilized: closed during the days and only “lit” some of the evenings. Most performance venues in medium-sized downtowns probably will have under 80 events a year. They can have positive impacts on local eateries and watering holes to the degree that they are active. Their impacts on retail, if any, have an overwhelmingly indirect and contingent route – through the new residents they might attract. Conversely, dark cultural centers can actually be detrimental to a downtown’s sense of vitality.

Ticket prices for these venues are usually relatively expensive – far above the price of local movie tickets, for example – so a substantial portion of middle income households are discouraged from attending their events.

There is little doubt that formal entertainment venues can be wonderful assets for a community. However, they demand a lot of resources and management expertise. Before a downtown decides to build one of these venues, local leaders must realistically assess whether they have the resources and management skills to not only build it, but also to maintain it and to run its programs without continued financial stress well into the future.

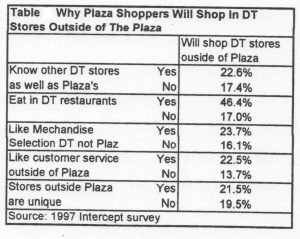

Restaurants. Restaurants are particularly important for downtowns not only because they are places where people can obtain needed nourishment, but also because they are places where folks go to have fun, be entertained and, most importantly, enjoy the company of other people. They are the essential driver of downtown vitality.

The growth of strong downtown restaurant niches and clusters has been another strong characteristic of successful downtowns of all sizes. They help bring downtowns alive after dark. Even though independent merchants are unlikely to be open during dinner hours and thus benefit from the restaurants’ customer traffic, they do benefit from the restaurant patrons’ lunchtime visits and their improved image of the district. Retail chains, with longer operating hours, are more likely to benefit directly from the restaurants’ customer traffic.

In small and medium sized communities, restaurants are relatively easy to start-up because of the relatively small market share they have to win to be viable as well as their districts’ comparatively low rents and labor costs.

The consumer market for restaurant fare is enormous: households in America spend relatively similar amounts for eating out as they do for meals prepared at home.

Any community that wants to build a strong CSD should first focus on strengthening its restaurant niche through recruitment and start-up assistance.

Movie Theaters. Though they have passed the digital projection/distribution divide that threatened to put many of them out of business, downtown movie theaters remain vulnerable. They are still threatened by home and electronic device movie watching – that is how most movies now are viewed. More importantly, they are vulnerable to some influential Hollywood execs who, because theaters provide such a small slice of their overall revenues, want same day release of new films through the theater and purely electronic distribution channels. Goodbye first run theaters.

Cinemart Theater in Forest Hills, NY,, its restaurant’s outdoor dining, with Eddie’s Ice Cream shop in background

For most downtowns and neighborhood commercial districts, cinemas are important parts of their CSDs. They have fewer user frictions than many other kinds of entertainment venues. They have comparatively reasonable prices; are open afternoons and evenings almost every day, and present frequent showings through the day. They also occupy large spaces, usually in highly visible locations. Failed cinemas are hard to redevelop and can be terrible eyesores.

When they get in trouble, there is usually not a lot of time available to save them. Savvy downtown EDOs should have an action plan ready to go, should their cinema face closure. In dealing with the digital divide many communities used new tools such as community based businesses and crowdfunding to save their theaters. These tools can be used readily by other downtowns should the need arise.

Parks and Public Spaces. These are not just green or open urban spaces where people can retreat for quiet relaxation. They are also places that are great for that most fundamental of entertainments, people-watching.

Bryant Park, once a festering venue for drug use and drug sale is now an exemplar engine of economic growth

Great parks and public spaces also usually have infrastructures and equipment that allow guests, at little or no cost, to engage in a range of leisure behaviors. Among them are a pond for sailing model boats; a boules court; a ping pong table; chess and checkers tables; a carrousel and an ice rink. The resulting activities constitute performances that other people-watching visitors can observe and enjoy.

Ice skating rink in Central Park Plaza in Valparaiso, IN.

Great parks and public spaces also often have performance spaces for events such as movies, plays, dance recitals, concerts, lectures, etc. The smart ones use temporary stages, so the same spaces can be used for multiple purposes over the year. For many small and medium-sized communities, this is the most cost effective venue they can have for entertainment and arts performances. But public space programming is not (at least initially) self-generating and government or some other entity must have the capacity to book and produce public events.

DANTH, Inc.’s research has shown that well-activated parks and public spaces are usually much cheaper to build, maintain and operate than any of the formal entertainment venues. Most communities already have them in key locations. Even where they are absent, the cost of a new build is generally far less that of a new enclosed venue. They have, by far, a lower ratio of operating costs per visitor/user. They also have the fewest user frictions. Access is free. Use of their infrastructure and equipment is either free or very affordably priced. They are open all day and often well into the evenings almost all year. No one has to make an appointment to use them or buy a ticket in advance of their visit. Visitors can stay 10 minutes or several hours.

Furthermore, successful parks and public spaces have a proven ability to increase values for properties from which they can be seen – even those 480 to 800 feet high and about 0.25 miles away. They also have a proven ability to improve adjacent property values to levels equaling the costs of initial construction or later renovation.

Downtowns of all sizes can have such successful parks and public spaces.

Downtowns that want to strengthen their CSD functions should make sure, early on, that they have an attractive, well activated park or public space. They can be very popular and produce the best bang for the buck of any type of downtown entertainment venue.

One note of caution. The success of a park or public space has far less to do with how beautiful it is – though it definitely should be attractive – than with how it is programmed by its infrastructure, equipment and events and the people it attracts. Unfortunately, this is not widely recognized.